A study published in Cell Reports Medicine reveals that bowel movement frequency significantly influences physiology and long-term health, with the best results linked to passing stools once or twice a day.

Previous research has suggested associations between constipation and diarrhea with higher risks of infections and neurodegenerative diseases, respectively.

But because these findings were seen in sick patients, it remains unclear whether irregular bathroom visits were the cause or result of their condition.

“I hope this work will open the minds of clinicians a little bit to the potential risks of not managing stool frequency,” lead author Sean Gibbons of the Institute for Systems Biology told AFP. , explaining that doctors often view irregular movements as nothing more than a “nuisance.”

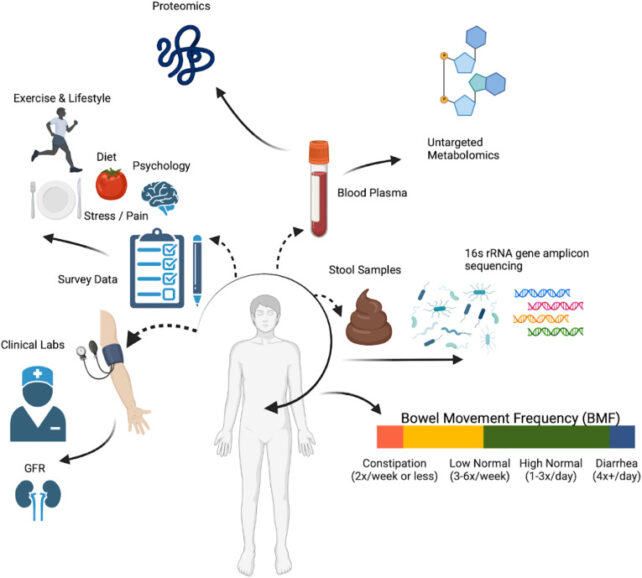

Gibbons and his team collected clinical, lifestyle, and biological data – including blood chemistry, gut microbiome, genetics and more – from more than 1,400 healthy adult volunteers with no signs active disease.

Participants’ self-reported bowel movement frequencies were categorized into four groups: constipation (one or two bowel movements per week), low-normal (three to six per week), high-normal (one to three per day), and diarrhea.

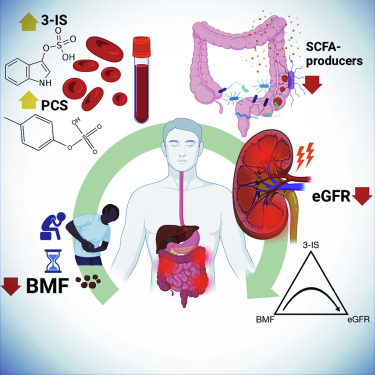

When stool lingers in the intestine for too long, microbes deplete available fiber – which they ferment into beneficial short-chain fatty acids – and ferment proteins, producing toxins like p-cresol sulfate and sodium sulfate. indoxyl.

“What we found is that even in healthy people who are constipated, there is an increase in these toxins in the blood,” Gibbons said, noting that these toxins are particularly heavy on the kidneys.

Key to fruits and vegetables

In cases of diarrhea, the team found clinical chemical signs indicating inflammation and liver damage.

Gibbons explained that during diarrhea, the body excretes excess bile acid, which the liver would otherwise recycle to dissolve and absorb dietary fats.

Fiber-fermenting gut bacteria, known as “strict anaerobes,” associated with good health, thrived in the “Goldilocks zone” of one or two poops a day.

However, Gibbons stressed that more research is needed to more precisely define this optimal range.

Demographically, younger people, women, and those with lower body mass index tend to have less frequent bowel movements.

Hormonal and neurological differences between men and women may explain this discrepancy, Gibbons said, as well as the fact that men generally consume more food.

Finally, by combining biological data with lifestyle questionnaires, the team created a clear picture of who typically falls into the Goldilocks zone.

“It was eating more fruits and vegetables, that was the biggest signal we saw,” Gibbons said, along with drinking lots of water, getting regular physical activity and ‘have a predominantly plant-based diet.

The next step in research could be to design a clinical trial to manage the stools of a large group of people, followed over an extended period to assess its potential in disease prevention.