new York

CNN

—

It’s not March 2020, but that sounds a lot like Herschel Wilson.

Wilson began building a small stockpile of essentials for his three pets and Tacoma, Washington-based family of five in August, after Donald Trump was named the Republican presidential candidate, with an economic agenda that called for higher tariffs.

Once Trump won the election, “that changed everything again and I started stockpiling pretty much everything,” Wilson told CNN. This includes canned goods, bottled water and, yes, lots of rolls of toilet paper. So far, he estimates he’s spent $300 on merchandise inventory since the election. Going forward, he said he plans to spend an extra $100 each month on top of his usual grocery spending.

Unlike earlier in the pandemic, when Wilson was also drawn to stockpiling, this time around his main concern isn’t necessarily not being able to find those goods. He is rather convinced that they will cost him much more if President-elect Trump carries out his tariff threats.

These include tariffs of 10% to 20% on all products imported into the United States, tariffs of 60% or more on products from China, and general tariffs of 25% on imports from Mexico and Canada.

Many trade experts and economists are skeptical that Trump will impose all the tariffs he has pledged to uphold and could use them as leverage. negotiation tactic. This could mean that some goods end up being excluded from ratesas was the case with the tariffs imposed by Trump during his first term. It is also possible that Trump will decide against imposing new tariffs on imports from certain countries.

Nevertheless, the tariffs he launched have the potential to significantly increase prices consumers pay for almost anything that isn’t entirely made in the United States, and there are very few products.

Wilson is in tune with this, especially as a small business owner. He and his wife operate Painting Panda Pottery Studio, where customers paint their own pottery, including mugs and plates. They often purchase the unpainted pieces of pottery from sellers based in the United States. But ultimately the goods come from China and other countries, he explained. “I know if there are tariffs, we’re going to have to pass them on to our customers,” he told CNN, meaning he would have to charge higher prices..

Scott Lincicome, vice president of general economics and trade at the Cato Institute, discourages individual consumers from hoarding goods. “We certainly don’t know if we’ll actually get this global tariff problem, and certainly not on day one,” he said, referring to Trump’s imposition of tariffs on all products. imported when he took office on January 20. impose higher rates on Mexico, Canada and China from the first day of his presidency. So building up inventory to try to save money in the future could be “preparation for something that will never happen,” he said.

Additionally, as seen during the pandemic, “consumer stockpiling can actually lead to higher prices and empty store shelves,” Lincicome said. Plus, any money spent on storage means consumers have less to spend in other areas.

Gaylon Alcaraz understands she’s taking a gamble by stockpiling assets, especially with more than $200,000 in student debt she accumulated while earning her doctorate and helping cover college tuition for two of her children.

But fears of potentially having to pay much more for goods in the future due to higher tariffs pushed her and her mother, whom she helps financially, to stock up on goods after the election.

“When I think about it logically, I sometimes feel like it’s irrational, but I just remember how hard it was during the pandemic when we couldn’t find certain things and when we did find them, they were very expensive,” said Alcaraz, a Chicago resident. resident who works as executive director of a nonprofit organization, told CNN.

“If we don’t need it, it doesn’t matter. We will always have it,” said Alcaraz, who lives alone. “Every time we see products on sale, every time we get paid, we say, ‘Let’s just stock up on products that we had trouble finding before, or were just really expensive.’ »

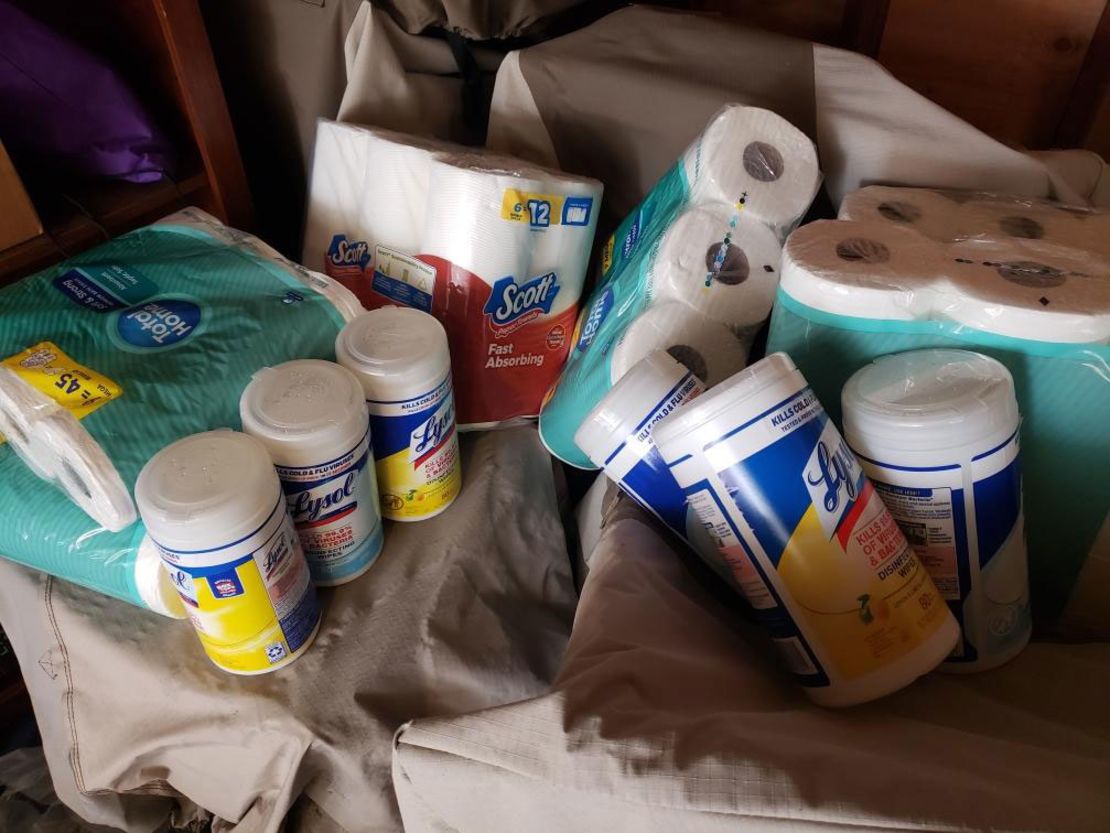

This includes infamous products that have experienced extreme shortages due to panic buying during the pandemic, such as toilet paper, Lysol wipes, paper towels, and other types of cleaning products. But when it comes to storing food, “it’s just a little bit too over the top for me.”

Ultimately, stockpiling feels like “robbing Peter to pay Paul,” she said, given the burden of debt on top of all her immediate living expenses.

It’s not just individuals trying to get ahead of potentially higher rates, large companies are doing it too.

For example, Patrick Hallinan, chief financial officer of Stanley Black & Decker, said at the company’s investor day last month that it was investing in building higher inventory levels “for a number of reasons, including not the least of which is customs tariffs.” The goal is to limit the extent to which the company might need to raise goods prices if tariffs rise as expected, he said.

During Trump’s first term, when higher tariffs were imposed on Chinese goods, “we were not proactive in setting prices,” he said. “The lesson we learn from this is that we’re going to be proactive about pricing going forward.”

Additionally, U.S. manufacturers, particularly those in the consumer goods sector, have recently “increased their buffer stocks to help mitigate any immediate increases in tariffs,” said John Piatek, vice president of GEP, a supply chain consulting firm, in a statement included in a statement. monthly report surveying 27,000 companies worldwide by GEP and S&P Market Intelligence.

Purchasing activity for imported goods among North American manufacturers reached its highest level in more than a year last month, according to the report.

Another approach companies are taking is working on contingency plans for when there is more certainty about potential new rates that will take effect, according to recent company earnings calls. These plans involve, in some cases, speeding up shipments out of countries where costs are expected to be higher and relocating some production.

Actions that big companies take, or plan to take, may ultimately soften the blow to consumers from potentially higher rates, Lincicome said.

In case higher tariffs don’t happen, Wilson, a father of three children under the age of 13, said none of the products he purchased would go to waste. “My kids eat a lot, so I don’t want to pay double the price I pay now, or even 20 percent more,” he told CNN. “I know the things I have now obviously won’t last four years. And that’s not the intention. It’s really about reducing expenses a little later.