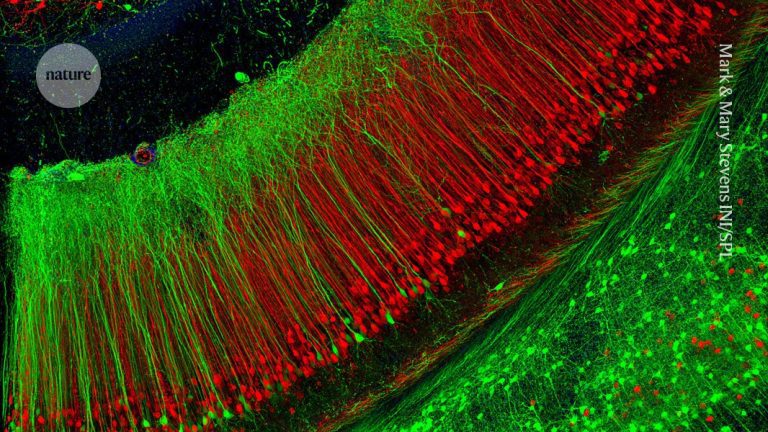

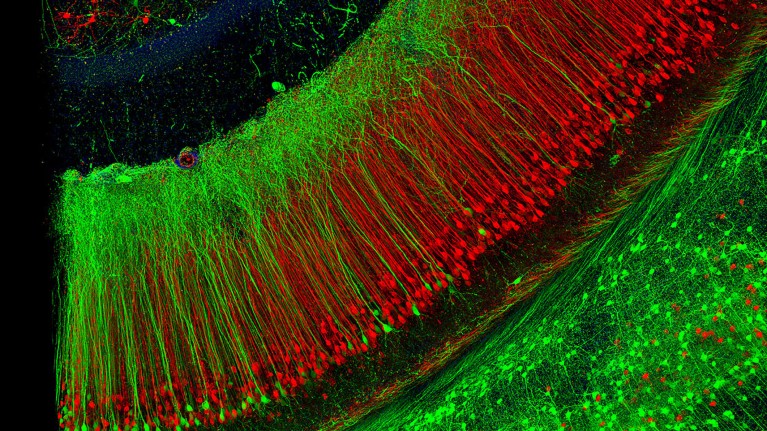

Artificially colored nerve fibers in a mouse’s hippocampus, the region of the brain where new memories are encoded.Credit: Mark & Mary Stevens Institute for Neuroimaging and Informatics/Scientific Photo Library

New clues have emerged about how the brain avoids “catastrophic forgetting” – the distortion and overwriting of previously established memories. when new ones are created.

A research team has found that, at least in mice, the brain processes old and new memories in separate sleep stages, which could prevent mixing between the two. Assuming this finding is confirmed in other animals, “I bet all my money that this segregation will also occur in humans,” says György Buzsáki, a systems neuroscientist at New York University in New York. . That’s because memory is an ancient evolutionary system, says Buzsáki, who was not part of the research team but once supervised the work of some of its members.

The work was published Wednesday in Nature1.

Window to the brain

Scientists have known this for a long time, during sleep, the brain “replays” recent experiences: the same neurons involved in an experience fire in the same order. This mechanism helps solidify the experience as a memory and prepare it for long-term storage.

To study brain function during sleepthe research team exploited a particularity of mice: their eyes are partially open during certain phases of sleep. The team monitored one eye of each mouse while it slept. During a phase of deep sleep, the researchers observed that the pupils shrank and then returned to their original, larger size repeatedly, with each cycle lasting about a minute. Neural recordings showed that most repetitions of brain experiences took place when the animals’ pupils were small.

Loss of sleep impairs smell memory, worm research shows

This led scientists to wonder whether pupil size and memory processing were linked. To find out, they used a technique called optogenetics, which uses light to trigger or suppress the electrical activity of genetically modified neurons in the brain. First, they trained mice designed to find a treat hidden on a platform. Immediately after these lessons, while the mice slept, the authors used optogenetics to reduce repetition-related bursts of neuronal firing. They did this during the small and large pupil phases of sleep.

Once aroused, the mice had completely forgotten the location of the treat, but only if firing had been reduced during the small-pupil phase. “We have erased the memory,” says Wenbo Tang, co-author of the work. Nature article and systems neuroscientist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

In contrast, when the team reduced the firing bursts of neurons in the large pupil phase shortly after a lesson, the mice went straight to the treat, making it clear that their new memories were intact.