Politics in 2025 will be dominated by a single dominant thought: Are things starting to improve?

The answer to this question will determine many other things in the political debate: the fortunes, mood and behavior of the government, the revival or not of the conservatives and the importance or not of everyone else.

2024 was a year of spectacular success for Labor, but their landslide general election victory already feels like it was a long time ago, with the new government taking on a tricky legacy and filling it with its own mistakes.

And we’re heading into 2025 with a cocktail of ingredients: a stagnant economy, an impatient electorate and an unstable world.

In a few weeks, we will witness the inauguration of Donald Trump.

An already unpredictable international context – from Ukraine to the Middle East – collides with the most unpredictable man ever to occupy the Oval Office.

The implications for trade, for climate change policy, for war and for peace are enormous.

The Prime Minister, stung by the nickname on social media that he is “never here Keir” because he is always on the international circuit, will inevitably find his attention drawn back onto the world stage, while arguing that this has a direct impact on millions of lives in the UK.

There are two inalienable truths in politics that bear repeating: governing is hard and assembling an elected opposition is hard.

And perhaps never more so than today, on both counts.

Governing in the 2020s is a pretty unforgiving business – just ask the last Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak or Starmer.

Among Sir Keir’s ministers, I have two recurring sentiments about the party’s first six months in power.

The first – and this is still visible in the eyes of ministers when they reflect on their work – is the enthusiasm, after years in the opposition wilderness, at the idea that they now have power and are called upon to make decisions every day.

But the second is the frustration of too many errors.

One minister told me he was fed up with what he saw as poor presentation and communication, particularly on difficult subjects like withdrawing winter fuel payments from millions of pensioners.

Another acknowledged that it had taken some time for them and their fellow ministers to move from being administrators, to mastering their new jobs and getting used to making decisions, to becoming politicians of high ranking within government and to make decisions in a broader strategic context.

“We are no longer the political wing of the civil service,” observed one Labor MP of the new government’s learning curve, which included the abrupt dismissal of the prime minister’s first chief of staff, Sue Gray. shortly after, I was leaked private details about his salary.

Politics at Westminster looks a lot more competitive than the numbers suggest: Labour’s mountainous majority means they will rarely feel even a slightly quickened pulse when it comes to votes in the House of Commons.

But one of the clichés of 2024, and it is true, is that support for Labor seems broad but shallow.

They won an overwhelming majority with just 34% of the vote, a lower vote share than any party forming a post-war majority government.

Opinion polls and approval ratings for both Labor and Sir Keir have come under strain since their election.

So what about the Conservatives and their new leader Kemi Badenoch?

They were sharper and more united than they could have been, given the magnitude of the defeat they suffered in July.

But privately, many conservatives fear they have not yet hit bottom.

They are awaiting, but not looking forward to, May’s local elections in England, where many Conservatives believe they will backtrack.

Indeed, the contested seats were last contested in 2021, a high point for Boris Johnson post-pandemic, so they have plenty of seats to lose.

Senior Tories tell me privately that they feel Badenoch has made a poor start to the toughest jobs.

Even her supporters admit they are relieved that she hasn’t done or said anything that could come back against her, given that she has a reputation for put your foot in your mouth every now and then.

And they hope she will shed skepticism, even suspicion, of journalists and speak out more in the new year to champion their cause.

And they will have to do it, because the word that we hear quite often from Conservative MPs is…

Reform.

The name of Nigel Farage’s party, Reform UK, sends shivers down the spines of many Conservatives, and Labor is not immune to concerns about it either.

Farage and his team are optimistic, speaking publicly and privately about their ambition to win the next general election.

This seems a fantastic proposal for a new group whose entire parliamentary party – five MPs – could fit in the back of a taxi.

But don’t forget that they received 4.1 million votes in the general election, 600,000 more than the Liberal Democrats.

The Reformers’ problem was that their votes were scattered, rather than accumulating in sufficient numbers in particular places to win many seats.

In 2025, we will have to keep an eye on two men within the Reform Party: the president, Zia Yusuf, and the new treasurer, Nick Candy.

They embody Nigel Farage’s dual objectives for his party: to organize more and generate money.

The party is trying to build local branches across the country, local nerve centers of enthusiasm which could be the cornerstone to winning more seats in local elections, devolved elections (coming to Scotland and Wales in 2026 ) and the next general elections.

Expect to see a series of regional conferences in the first weeks of the new year to try to spur this growth.

The Lib Dems have had an unforgettable 2024.

They won beyond their dreams and Sir Ed Davey now leads a party of 72 MPs.

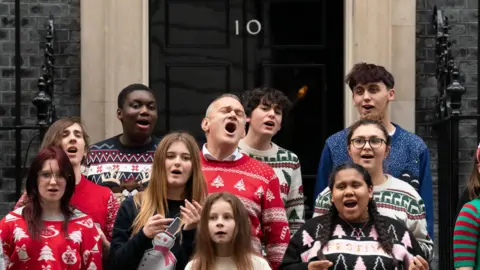

Sir Ed remains determined to do politics with a smile – take his The Christmas single is the latest example – and try to take ownership of issues of social protection, young carers and health services.

The party is trying to maximize the visibility that its status as a third party in Westminster gives it – Sir Ed continued. Have I got any news for you recentlyfor example, although such invitations can be tricky.

In the coming weeks, don’t be surprised if he appears to talk about foreign affairs and bypasses the largely pro-EU noise we’ve heard from the Labor Party by talking about a potential future for the UK within of the customs union of the European Union.

The party also looks forward to local elections in May, particularly in counties including Devon, Surrey, Shropshire and Wiltshire.

The challenge for Sir Ed will be to convert a much larger parliamentary party into influence in an era of majority government and noisy opposition parties.

The SNP had a terrible 2024: almost destroyed in the general election by Labor’s rampant comeback in Scotland.

But at the end of the year, in front of high-ranking figures, their mood was less gloomy than it could have been.

The argument ended the so-called wasp women and Labor maintaining the two-child benefit cap are just two examples where the SNP hopes to highlight clear differences between itself and the Labor Party, in the countdown to the Scottish Parliament elections in 2026.

Green MPs at Westminster are wearing plenty of smiles as 2025 approaches.

For starters, we now say the Greens in the plural when we talk about them – for the first time, there is more than one.

They have seen their membership numbers reach around 60,000 and they also hope to increase their presence on local councils in the English local elections in May.

Senior figures point out that they are currently part of the administration in more than 10% of local councils in England and Wales and finished second to Labor with 40 seats in the general election.

In some of these places they are miles behind, but in others there is at least a chance that they could, over time, capitalize on discontent with the Labor Party and attract Labor left voters in their direction. Let’s see.

And don’t forget Plaid Cymru; the parliamentary group known as the Independent Alliance, which includes former Labor leader Jeremy Corbyn; and Northern Ireland’s parties, all of which have their own concerns and campaigns – and can cause divisions among ministers inside and outside Parliament.

So much for politics in 2025.

This may not be a general election year.

But I think it will be lively.