December 19, 2024

4 min reading

Trump’s choice for NIH director could harm science and public health

As a possible avian flu outbreak approaches, Donald Trump’s choice of Jay Bhattacharya, a scientist critical of COVID-related policies, for the NIH is a bad decision for science and public health.

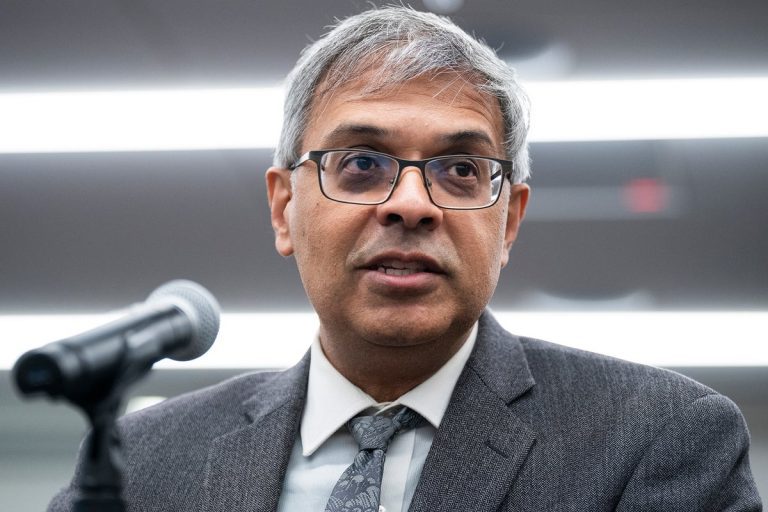

Jay Bhattacharya speaks during a roundtable discussion with members of the House Freedom Caucus on the COVID-19 pandemic at the Heritage Foundation on Thursday, November 10, 2022.

Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images

President-elect Donald Trump wants Jay Bhattacharya, a physician-scientist and economist at Stanford University, to lead the National Institutes of Health. The NIH is a global scientific powerhouse. Its mission is “to seek fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior of living systems and the application of this knowledge to improve health, prolong life, and reduce disease and disability.”

Most politicians, even when criticizing the agency, recognize the good it has done in developing effective public health measures. Cancer death rates continue to decline, for example, thanks to the work of NIH investigators in prevention, detection and treatment.

Bhattacharya doesn’t see the agency’s successes that way. In his podcast Science on the fringesBhattacharya recently he said he was surprised by “authoritarian tendencies in public health”. He addressed a similar theme in a Interview with Newsmax: “(We must) transform the NIH from something that is (used) to control society into something that is aimed at discovering the truth to improve the health of Americans.”

On supporting science journalism

If you enjoy this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Scientists who apply for NIH funding, serve on peer review committees, and administer grants would be surprised to learn that they control the company. They do science. Allegations of authoritarianism serve as a smokescreen to promote a particular agenda that could harm the NIH. Bhattacharya’s scientific agenda is political: pitting concerns of personal autonomy against evidence-based public health science. This does not sit well with NIH management.

Bhattacharya never explained how the NIH controls society, given its role as a research institution, and it is difficult to see how it would do so, except perhaps by setting research priorities and awarding funding based on expert review. Is he against public health legislation that controls lead emissions in vehicles, imposes vaccine requirements for children attending public schools, and encourages folate fortification of bread and foods? fluoride in drinking water? This legislation has improved population health in terms of cognitive performance, infectious disease burden, neural tube defects during pregnancy, and oral health, respectively. Is this the kind of control he fears?

Public health authorities decide on a population health promotion measure based on science, often for vulnerable people unaware of the health risks, when the health benefits are clear. NIH research provides evidence for these public health measures. It is fair to debate the quality of scientific evidence and population health benefits versus restrictions on autonomy and choice, but establish mechanisms to manage population health risks and formulate recommendations based on this evidence does not constitute authoritarianism, and making such a comparison is not the right way to proceed. doing good science or building trust.

Bhattacharya’s views are another unfortunate legacy of the COVID pandemic, when he opposed so-called public health excesses in the country. Great Barrington Declaration in 2020. The statement asserted that isolating only those most at risk and allowing the continued spread of COVID among healthier people would build herd immunity without a substantial increase in COVID mortality. In response, public health officials and NIH leaders criticized Bhattacharya based on scientific data: in a context of asymptomatic viral transmission, high contagiousness, and inevitable mixing of populations, such a strategy of “targeted protection” was unlikely to protect vulnerable populations. Bhattacharya called this censorship and I tried in vain to convince the Supreme Court to weigh against the social networks which abandoned his messages.

This personal dig is a diversion and should not obscure the central objective of American public health policy during the pandemic. Science has supported school closures, work-from-home policies, restrictions on large gatherings in public spaces, and face mask requirements as effective ways to reduce hospitalization surges and save time for vaccine development. You can challenge the science, as many have done; but it is not authoritarian to use science for political purposes. Likewise, you may value personal autonomy and resist vaccination or mask mandates, but relying on scientific evidence to support these measures does not mean that scientists “have engaged in censorship, data manipulation and disinformation,” as Trump falsely claimed to justify his candidates. .

Scientific or public health authoritarianism is not responsible for the pandemic’s heavy toll in the United States. Structural factors such as income inequality and access to health care have been the main drivers of COVID mortality. To prepare the country for the next pandemic as NIH Director, it would be far more effective to invest in pandemic preparedness and infectious disease research and, beyond that, to ensure that everyone has access to health care. health.

Indeed, proposed remedies to make science less authoritarian, such as shifting NIH funding to states in the form of “block” grants (recommended by the conservative political agenda) Project 2025), will not promote “non-authoritarian” public health but will almost certainly degrade the quality of American science. Will states be able to match the NIH peer review system, held worldwide as the exemplar of transparent, confidential, and impartial evaluation based on merit and scientific consensus? It is difficult to imagine how a decentralized state-level effort could produce more equitable assessment or science with greater impact. Won’t scientists in certain states be able to fund research on family planning or women’s health, for example?

We don’t know what other policies Bhattacharya might propose. Ban viruses gain of function research? Eliminate research on fetal tissue and restrict studies using animal models? Funding change away from infectious diseases research, as RFK, Jr. proposed, Trump’s choice to lead the Department of Health and Human Services? Give peer review committees less influence in determining scientific merit?

The best way to “depoliticize science,” if that is your concern, is to not intervene and let scientific research lead investigation and peer review determine funding priority. The “authoritarianism” that Bhattacharya rails against is often just the application of science to improve the health of the population. Contrasting personal autonomy with the application of science to policy is fine for vanity webcasts and think tanks, but inappropriate for NIH leadership. If he prefers to focus on promoting personal autonomy in pandemic policy, he may be appointed to the wrong agency. Bhattacharya is not what the NIH needs.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the opinions expressed by the author(s) are not necessarily those of Scientific American.