The tattoo of plants from the biologist Liz Haynes reminds him of an inspiring mentor.Credit: Justin Kibbel

Kristin Barry had wanted a tattoo for years, so when she finished her doctorate in neuroscience in 2019, she knew it was time. “It was logical that once I had my doctorate, I would commemorate it in this way,” she said. Barry’s research has focused mainly on hearing loss disorders, such as tinnitus, and has spent a lot of time looking at the hearing neurons of thalamus, nerve cells that help treat sound. These were often colored using the Golgi method, highlighting the cell body and the dendrites of the neuron that resemble the roots and tree teas – and would do a good fine tattoo.

In 2021, she obtained the tattoo – rightly so, behind her ear. “I really didn’t expect my tattooing as much role in my identity, but it looked right,” said Barry, who is now a researcher at the University of Western Australia and at Curtin University in Perth.

She is not alone. Many scientists mark research achievements and career stages while heading for a tattoo fair.

“It’s one thing to put on your CV” I wrote an article on this subject “, but that’s another thing to say” I’m going to put it on my skin and wear it with me for the rest of my life “, explains scientific journalist Carl Zimmer, author of the 2011 book Scientific ink: obsessed science tattoos. “It is a different level of connection.”

Behind ink

The inspiration for Zimmer’s book came from an unlikely place: a swimming pool for the swimming pool for its nephew. The children and the parents all jumped in the water, and it was the first time that he noticed that one of his friends had a tattoo on his shoulder.

“He is a neuroscientist, and he began to explain to me how he had written his wife’s initials in the genetic code,” says Zimmer, who does not himself have tattoos. Zimmer thought: “It’s extremely geek, but still cool”.

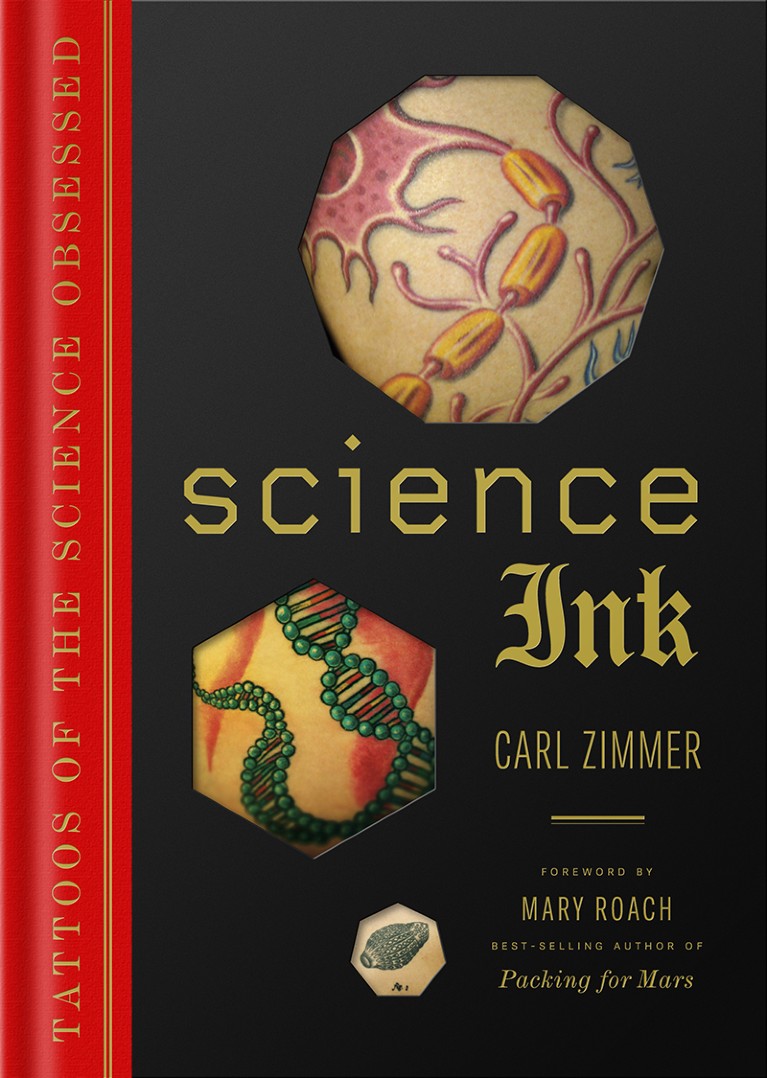

Scientific ink By Carl Zimmer offers hundreds of photos of tattooed scientists.Credit: Carl Zimmer / Union Square & Co

At the time, Zimmer was a passionate blogger. With permission, he posted a photo of his friend’s tattoo, asking if it was a common thing among scientists.

“These scientists I spoke to generally wore black shirts and coats,” he said. “Maybe they also had tattoos that I didn’t know.”

Zimmer was quickly flooded with emails and photos of tattooed scientists, which led him to make a more concerted call for his book. Although the book only presents 300 models, Zimmer estimates that it has seen 1,000 scientific tattoos over the years. There were many bodies decorated with double -strand DNA propellers. Some wore Darwin’s pinsons, birds whose study helped Charles Darwin demonstrate his theory of evolution. Others had a mass equivalence formula of mass energy from Albert, Albert, E = MC2. The tattoos lasted all scientific disciplines and many, discovered Zimmer, were specific and deeply significant only for the carrier.

The tattoo round of Yoshi Maezumi captures an instantaneous of his research career. He started with a drawing of a species of hummingbird from the Amazon forest – the doctorate of Maezumi at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City was in paleoecology in the region. But over time, design has grown to include other species that it studied.

“I have been working with the same artist for about three years, and each time I really felt to include something that I studied, or a new plant species that came to my work, we would add it,” explains Maezumi, who joined the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropy in Jena, in Germany, in 2022.

Although she no longer always notices her tattoos in the mirror – something she says is true for many people with them – it is a way to immortalize special moments. And while some of her tattoos are linked to science, she also has tattoos commemorating important people in her life.

Scientific careers and mental health

“Tattoos, for me, are really personal and like sentimental memories, almost like a newspaper or an album of things that I collected along the way,” she says.

Many tattoos adorning Matt Taylor, physicist of the European Space Agency (ESA) in Noordwijk, in the Netherlands, are not on the theme of science. But his right leg, which he calls his “mission leg”, has conceptions linked to two important career stages: the cluster mission, the first to investigate the way in which the solar wind of the sun interacts with the magnetic field of the earth in 3D, and Rosetta, which was the first mission to return, orbit and deploy a Landa on a comet.

“When I joined Rosetta in 2013, I came just before the spacecraft came out of hibernation,” he said. “When you move into a team like this, which has a fairly long story, you have to somehow convince them that you are determined to support them. And so I made a wish that if Rosetta came from hibernation, I would tattoo.”

Liz Haynes, biologist of the Department of Cellular Biology and Regenerative at the University of Wisconsin – Madison, also obtained a tattoo to mark a pivotal moment of his scientific career. The image, of the plant she studied in her undergraduate laboratory, recalls the positive experience and the lessons she learned from her mentor at the time.

“One of the things I took is that I really wanted to be that for someone in the future, helping to show them the way to this career, to guide them to higher education, to influence them positively and to really give them a house in the laboratory,” she explains.

Professional perception

All tattooed scientists interviewed for this article alluded to their body art presenting themselves non -professional to certain people and potentially as a hypergia. In the early 2010s, when Yesenia Arroyo obtained a set of planetary symbols tattooed on their forearm, they did not know how it would be perceived. They already had a tattoo in their spine, but it was the first tattoo that would be fully visible in a professional setting.

I remember being nervous who was going to exclude me from the jobs. People were going to look at me and say to me: “Well, it’s not professional”, “explains Arroyo, research assistant and specialist in NASA communications in Greenbelt, Maryland, who also has a tattoo with electrons configurations for carbon and oxygen inside the arm.

In 2014, ESA asked Taylor to Tattoos During a major media event (although the agency then started using them as a subject of discussion to promote science). Taylor notes that the tattoo round on his arm was a “big step”.

“I already had a permanent position, so I think I would have been more reluctant if I still looked for a job,” he said.

But prejudices towards tattoos change, and they become more common. “I have the impression that it has definitely become much more relaxed, and it could be people on the younger field, so we probably share a lot of the same values,” explains Arroyo.

The planetary symbols on the research assistant Yesenia Arroyo often have conversations with non-sciences.Credit: Daniel Zarzuela Perez

Todd Disotell, a biological anthropologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, which was presented in Zimmer’s book, also sees a generational fracture in tattoos. The 62 -year -old obtained his first tattoo – a double DNA propeller – for his 40th anniversary. And after having bitten the ball with the first, he continued to obtain 30 others, covering both his scientific and science fiction interests. Although the decision to wait for the forties to obtain a tattoo is not necessarily because of potential stigma, he notices that he is an aberrant kind.

“My older colleagues, unless they have a naval anchor on their arms, very few of them have a tattoo,” he said. “All my colleagues who are younger than I have them.”

That said, many scientists interviewed noted that despite increasing acceptance, they considered cooling during their tattoo.

“If I wear long pants and a long -sleeved shirt, none of my tattoos is visible,” says Disotell. “So I would never do a neck, face or head – in addition to imagining how painful it would be.”

Haynes also notes that even if she never felt the need to hide her tattoos, get something that could be covered by long sleeves was a factor in the examination of the tattoo.

However, she never felt judged to have tattoos, adding that cellular biologists are “intrinsically eccentric people” who embrace them.