Register for the Wonder Theory Science newsletter from CNN. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific progress and more.

Cnn

–

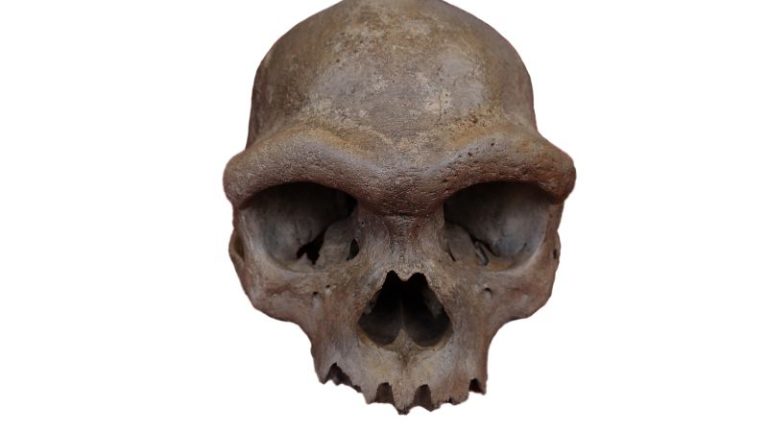

An enigmatic skull recovered from the bottom of a well in northeast of China in 2018 triggered the intrigue when it did not correspond to any prehistoric human species before. Now scientists say they have found proof of the place where the fossil is, and this could be a key room in another cryptic evolutionary puzzle.

After several unsuccessful attempts, the researchers managed to extract genetic equipment from the fossilized skull – Nicknamed Dragon Man – binding it to an enigmatic group of first humans known by name Denisovans. A dozen fragments of Denisovan fossilized bones had already been found and identified Using old DNA. But the small size of the specimens offered little idea of what this dark population of ancient hominines looked like, and the group has never been awarded an official scientific name.

Scientists generally consider skulls, with revealing bumps and ridges, the best type of fossilized remains to understand the form or appearance of an extinguished hominine species. The new conclusions, if confirmed, could effectively put a face on behalf of Denisovan.

“I really think that we have clarified part of the mystery surrounding this population,” said Qiaomei Fu, professor at the Institute of Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, which is part of the Chinese Academy of Beijing Sciences, and the main author of the new research. “After 15 years, we know Denisovan’s first skull.”

The Denisovans were discovered for the first time in 2010 by a team which included FU – who was then a young researcher at the Max Planck Institute for evolving anthropology in Leipzig, Germany – old DNA contained in a small number fossil found in the Denisoa cave in the Altai mountains of Russia. Additional remains have discovered in the cave, from which the group takes its name, and elsewhere in Asia continues to add to the image still inability.

The new research, described in two scientific articles published on Wednesday, will be “definitively part of, if not the biggest articles in paleoanthropology of the year”, and will stimulate the debate on the ground “for a while”, told Ryan McRae, a paleoanthropologist at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC, which was not involved in studies.

The results could help fill the gaps at a time when Homo Sapiens was not the only humans wandering on the planet – and teaching more scientists on modern humans. Our species once coexisted for tens of thousands of years and agreed with Denisovans and Neanderthals before the two disappear. Most humans today wear a genetic inheritance of these ancient meetings. Neanderthal fossils have been the subject of studies for a century, but rare details are known on our mysterious Cousins of Denisovan, and a skull fossil can reveal a lot.

A worker from the city of Harbin, in northeast China, discovered the dragon’s skull in 1933. The man, who built a bridge on the Songhua river, when this part of the country was under Japanese occupation, brought the specimen and stored it to the bottom of a well for the maintenance of security.

The man has never recovered his treasure, and the skull, with a tooth always attached in the upper jaw, remained unknown from science for decades until his loved ones learned before his death. His family donated fossil to Hebei Geo University, and the researchers described it for the first time in a set of studies published in 2021 which found The skull at least 146,000 years.

The researchers argued that the fossil deserves a new species name given the unique nature of the skull, appointing it homo longi – which is derived from Heilongjiang, or Black Dragon River, the province where the skull was found. Some experts of the time have hypothesized that the skull could be Denisovan, while others have gathered the skull with a Fossil cache difficult to classify Found in China, resulting in intense debate and the creation of particularly precious molecular data from the fossil.

Given the age and the background of the skull, Fu said that it knew it would be difficult to extract ancient DNA from the fossil to better understand where it adapts in the human family tree. “There are only bones of 4 sites of more than 100,000 (years) in the world that have ancient DNA,” she noted by e-mail.

Fu and his colleagues tried to recover old DNA from six samples taken from the surviving tooth of Dragon Man and the sustainable bone of the skull, a dense piece at the base of the skull which is often a rich source of DNA in fossils, without success.

The team has also tried to recover genetic equipment from the dental calculation of the skull – the Gunk left on the teeth which can over time form a hard layer and preserve DNA from the mouth. From this process, the researchers have managed to recover mitochondrial DNA, which is less detailed than nuclear DNA but revealed a link between the sample and the genome of Denisovan known, according to a new article published in the newspaper.

“Mitochondrial DNA is only a small part of the total genome, but can tell us a lot. The limits are in its relatively small size compared to nuclear DNA and in the fact that it is what is what is noise on the matrilineal side, not both biological parents,” said McRae.

“Consequently, without nuclear DNA, it could be made in question that this individual is a hybrid with a mother of Denisovan, but I think that this scenario is quite likely that this fossil belonging to a complete Denisovan,” he added.

The team has also recovered the protein fragments of pump bone samples, whose analysis also suggested that the dragon skull belonged to a population of Denisovan, according to a separate article published Wednesday in the Science Journal.

Together, “these documents increase the impact of the establishment of the Cranium Harbin as Denisovan,” said Fu.

The molecular data provided by the two articles are potentially very important, said anthropologist Chris Stringer, research manager in human origins at the Natural History Museum in London.

“I have collaborated with Chinese scientists on new morphological analyzes of human fossils, including Harbin,” he said. “Combined with our studies, this work makes it more and more likely that Harbin is the most complete fossil of a Denisovan found so far.”

However, Xijun Ni, professor at the Institute of Paleontology of Vertebrates and Paleoanthropology in Beijing which, with Stringer, worked on the initial research of Dragon Man but not the latest studies, said that it was careful about the outcome of the two documents because some of the DNA extraction methods used were “experimental”. Nor also said that it found strange that DNA was obtained from the surface dental calculation but not inside the tooth and the Pepreto bone, since the calculation seemed to be more exposed to potential contamination.

However, he added that he thought it is likely that the skull and other fossils identified as Denisovan come from the same human species.

The objective of using a new extraction approach was to recover as much genetic material as possible, said Fu, adding that the dense crystalline structure of dental calculation can help prevent the loss of host DNA.

The signatures of FU protein and his team have been brought indicated “an allocation of Denisovan, with other very improbable attributions,” said Frido Welker, an associate professor of biomolecular paleoanthropology at the Globe Institute of the University of Copenhagen in Denmark. Welker has recovered Denisovan’s proteins from other candidate fossils but was not involved in this research.

“With the Cranium Harbin now linked to Denisovans on the basis of molecular evidence, a larger part of the fossil hominines file can be reliably compared to a known Denisovan specimen based on morphology,” he said.

A name and a face for Denisovans

With Dragon Man’s skull now linked to Denisovans on the basis of molecular evidence, it will be easier for paleoanthropologists to classify other remains of potential Denisovan from China and elsewhere. McRae, Ni and Stranger all said they thought it was likely that Homo Longi would become the official name of the Denisovans species, although other names have been proposed.

“Renamed it all the continuation of Denisovan’s evidence as Homo Longi is a bit of a step, but which has a good position since the scientific name Homo Longi was technically the first to be, now linked to the Fossils of Denisovan,” said McRae. However, he added that he doubted that the informal name of Denisovan goes anywhere anywhere, suggesting that this could become a shortcut for the species, as the Neanderthal is in Homo Neanderthalensis.

The results also make it possible to say a little more about what Denisovans could have looked like, assuming that the Skull Dragon Man belonged to a typical individual. According to McRae, the former human has had very strong forehead ridges, brains “the size of the Neanderthals and modern humans” but teeth larger than the two cousins. Overall, the Denisovans would have had an appearance in block and robust.

“As for the famous image of a Neanderthal dressed in modern outfit, they would probably still be recognizable as” humans “,” said McRae.

“They are always our more mysterious cousin, just a little less than before,” he added. “There is still a lot of work to do to understand exactly who was the Denisovans and how they are linked to us and other homes.”