A new US Congress will convene in Washington, DC on January 3. But for the first time in 18 years, a key Republican leader will no longer be at the helm: Senator Mitch McConnell.

Since 2007, McConnell has led the Republican Party in the Senate, leading members of his caucus through four different presidencies and countless legislative hurdles.

Experts say his tenure as the longest-serving party leader in the Senate will ultimately be remembered as an inflection point for Republicans and Congress as a whole.

Under McConnell, American politics has moved away from the back-slapping, consensus-building system of earlier eras. Instead, McConnell helped usher in a period of hyper-partisan, outsized politics that paved the way for the likes of the new president Donald Trumpthe leader of the Make America Great Again (MAGA) movement.

“Above all, he extended a pattern of minority obstruction in the Senate,” Steven S Smith, professor emeritus of political science at Washington University in St Louis, told Al Jazeera.

Smith pointed out that McConnell led a Republican majority for only six of his 18 years leading the Senate. The remainder of his term was spent mobilizing a minority within the 100-seat Senate to disrupt the agenda of the rival Democratic Party.

“Second, he will be known for deepening partisan polarization in the Senate,” Smith said. “While McConnell was not a conservative or MAGA extremist by today’s standards, he was a deeply partisan leader.”

Despite his commitment to the Republican Party, some see McConnell as a potential bulwark against figures like Trump, with whom he clashed in the past.

Although he is resign as party leaderMcConnell intends to remain in the Senate for the remainder of his six-year term. But it remains to be seen how much McConnell will obstruct Trump’s ambitious agenda for his second term.

“I would be very surprised to see him be provocative in public. His influence is going clandestine,” Al Cross, a veteran journalist and columnist who covered McConnell’s tenure, told Al Jazeera.

“I usually play the bad guy.”

McConnell had a long and storied career in the Senate. In 1984, he made his first bid for a House seat, ousting an incumbent Democrat.

Since then, he has remained undefeated. In 2020, he won his seventh consecutive term.

His rise to the top of the Senate came without significant opposition. The 2007 retirement of former Senate Republican leader Bill Frist left the position vacant.

But from his earliest days as Senate leader, McConnell cultivated a reputation as a hard-liner and obstructionist.

In his first year as Republican leader, the New York Times described him as acting with “near-robotic efficiency” to suppress Democratic policies, despite being the leader of a minority in the Senate.

“Mr. McConnell and his Republican colleagues are playing such tight defense, blocking almost every bill proposed by the slim Democratic majority, that they are increasingly able to dictate what they want,” wrote the journalist David Herszenhorn.

McConnell quickly adopted his visibility as a partisan warrior, a self-proclaimed “reaper” for progressive proposals.

One editorial dubbed him “Senator No” for his refusal to work across the aisle. McConnell himself once greeted reporters by saying, “Darth Vader has arrived.”

“In the three decades that I have been a United States senator, I have been the subject of numerous profiles,” McConnell wrote in the opening lines of his 2016 memoir. “I usually play the bad guy.”

Smith, a professor at the University of Washington, described McConnell as having sparked a “transformation” in the Senate because of his tough approach.

Before McConnell’s leadership, Smith said the Senate experienced only “occasional minority obstruction.” But eventually the House became known in political circles as the “60-vote Senate.”

This nickname refers to the 60 votes required to overcome a minority filibuster, also known as a filibuster.

Under McConnell, Smith explained, “acting on legislation of any significance would face minority obstruction and require 60 votes for closure.”

Folding standards

One of McConnell’s most controversial moments came in 2016, with death by Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia.

Normally, when a judge dies, the sitting president has the right to appoint a replacement. But Scalia’s death came 11 months before a crucial presidential election. And the president at the time, Democrat Barack Obama, was nearing the end of his final term.

McConnell produced a superb – and rapid – political bet. Hours after Scalia’s death, the Republican leader announced he would refuse to call a vote to confirm Obama’s chosen replacement.

“The American people should have a say in choosing their next Supreme Court justice. Therefore, this position should not be filled until we have a new president,” McConnell said in a statement.

Left-wing publications like The Nation denounced McConnell’s decision as an attack on the U.S. Constitution. “This refusal has shattered norms,” wrote journalist Alec MacGillis in the publication ProPublica.

But McConnell’s strategy has shifted the balance of power on the ground for generations to come.

In November of that year, American voters elected Trump – a political newcomer – to his first term in the White House, paving the way for further changes in Washington’s norms.

Trump finally nominated three right-wing judges to the Supreme Court, including one to replace Scalie. This cemented a conservative supermajority on the bench, expected to shape American law for generations to come.

Trump then credited McConnell as his “ace in the hole” and “partner.”

“Mitch recognized, as did I, that because judges are appointed for life, the impact of judicial appointments can be felt for thirty years or more,” Trump wrote in a preface to McConnell’s memoir. “Transforming the federal justice system is the ultimate long-term task! »

A Trump rivalry

But as a bold new Trump administration approaches in 2025, McConnell has increasingly pronounced against the president-elect and his isolationist “America First” platform.

The two Republican leaders have repeatedly said butted headsand their relationship is particularly icy.

Trump openly called McConnell an “old crow” and vilified his “China-loving wife” Elaine Chao, a slap in the face for his Asian heritage.

McConnell, meanwhile, responded with combative remarks of his own, implying parallels between Trump and the isolationism of the 1930s.

“We are in a very, very dangerous world right now, reminiscent of the world before World War II,” McConnell told the Financial Times in December. “Even the slogan is the same. “America First.” That’s what they said in the 1930s.”

After leaving his leadership post in January, McConnell is expected to take on the role of chairman of the Senate Defense Appropriations Subcommittee.

In his new position, he will likely advocate for strengthening the U.S. military to counter threats from adversaries like Russia, Iran and China.

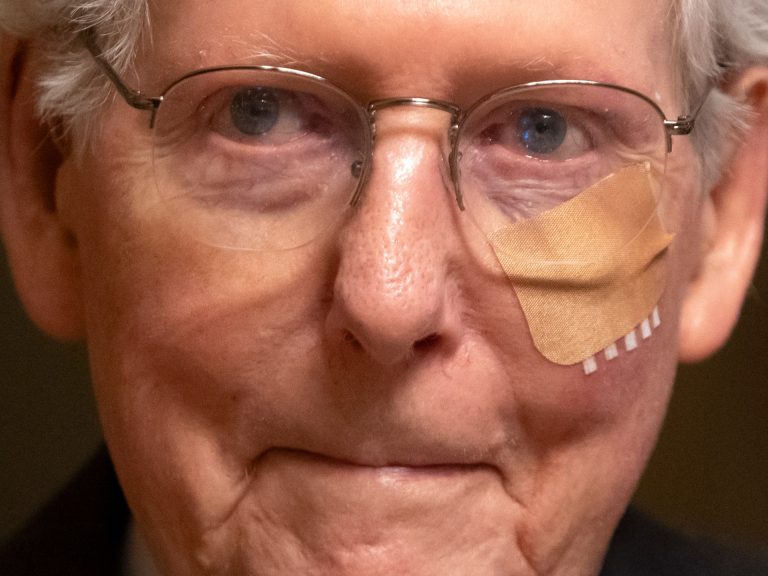

However, at 82 years old, with health challenges including a recent fall, experts say McConnell is unlikely to put up much resistance to the incoming Trump administration.

“Given that Senator McConnell is no longer in a leadership position and given his physical frailty, I don’t expect much sustained opposition from him,” the political scientist told Al Jazeera. Harvard University, Daniel Ziblatt.

“It is possible that he will cast a dissenting vote here or there, which could make a difference. But his track record doesn’t let me hold my breath.

No greater institutionalist

Still, Herbert Weisberg, a political science professor at Ohio State University, predicts McConnell could act in a casual capacity. dissenting voiceespecially as the Senate evaluates some of Trump’s controversial nominees for high-level government positions.

“He would normally prefer to defer to a Republican president for nominations, but he will be cautious about unusual Trump nominees. He might be willing to vote against some, but not all,” Weisberg told Al Jazeera.

Already, McConnell – a survivor of childhood polio – has published a public warning new administration officials to “avoid” efforts “to undermine public confidence” in “proven remedies” lest they derail their Senate confirmation hearings.

The statement came immediately after Trump’s health care nominee. Robert F. Kennedy Jr. was linked to an attempt to revoke the approval of the polio vaccine in the New York Times.

But a single Republican is unlikely to block a nomination or bill, as Steven Okun, an analyst on U.S. politics, government and trade, has pointed out.

The Republicans hold a Majority of 53 people in the new Senate. And many in the party strongly support Trump’s leadership.

Assuming a united Democratic opposition, “four Republican senators would be needed to prevent anything a future President Trump proposes in the Senate,” Okun explained.

McConnell is unlikely, Okun added, to take on the role of dissident — “only when Donald Trump pursues the most aggressive actions that would go against the American national interest.”

After all, party loyalty is a key tenet of McConnell’s leadership. And experts like journalist Cross believe McConnell won’t want to miss an opportunity to use the power of the Senate to shape presidential policy.

“I don’t know a greater institutionalist than Mitch McConnell,” Cross said. “He loves the Senate, it’s what he aspires to be. He does not want to give up his role of advice and consent.”