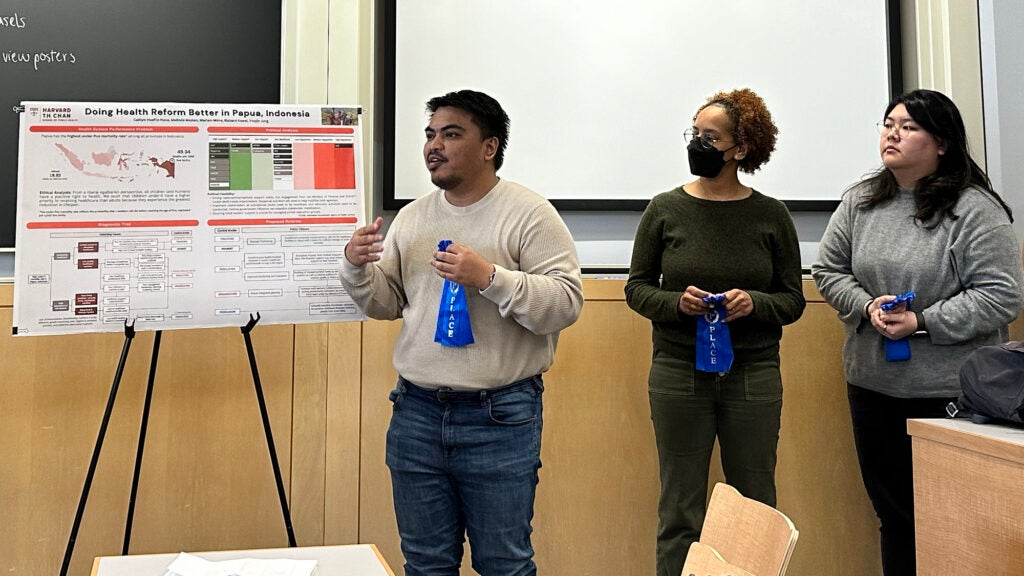

Students and faculty members after the final poster session of the course. Photo: Courtesy of Sun Kim

When Indonesian doctor Richard Kowel, MPH ’25, got a job with UNICEF in his country’s Papua province four years ago, he was supposed to focus on eliminating malaria. But he found himself working to meet multiple additional needs unmet by the health care system. This fall, he came to the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health to learn skills that would help him do more to improve public health in his country. Six months into his program, he’s already off to a good start: a class project in which he played a key role landed him and his teammates a meeting with the Indonesian Ministry of Health.

The project involved the fall 1 course “Doing Health Reform Better”, taught by Michael ReichTaro Takemi, professor emeritus of international health policy. The students formed teams and chose a country to analyze a health system performance problem and propose reforms. This year’s teams included Colombia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Guatemala, Florida (USA) and a Kowel-trained team from Papua and Indonesia. The course uses the founding book as a text, Making health reform a success: a guide to improving performance and equityby members of the School’s faculty: the late Marc J. Roberts, William Hsiao, Peter Bermanand Reich.

Kowel said the team chose to focus on mortality rates among children under five, which can be an indicator of weaknesses in a country’s primary care system. Papua’s under-five mortality rate of 49.04 per 1,000 live births is more than twice the Indonesian national average, reflecting inequalities in access to vaccinations, neonatal care and to treatments for common childhood illnesses, according to the team’s findings. Their paper’s recommendations included carrying out a number of financial and regulatory reforms, in addition to implementing culturally sensitive health promotion strategies in collaboration with local leaders.

Kowel provided the policy analysis for the project and said he appreciated what everyone else could bring to the team, including his friend Melinda Mastan, MPH’25, also from Indonesia, who led the analysis of the problem . “The dynamic between the various members of our team made the project a success,” he said. “We were able to trust each other’s expertise and be open to learning from each other. »

The Indonesian team took first place in class voting after a final poster session. Kowel, who had previously worked with the Indonesian Ministry of Health, thought his team’s research might be useful to them. Encouraged by Reich, he sent the project to Maria Endang Sumiwi, director general of public health. She responded to him a few hours later and arranged a Zoom meeting that week.

Kowel said he was surprised to receive an invitation to a meeting, especially since it involved not only Sumiwi, but also a team of directors and a deputy from the Ministry of Health , including officials from Papua. “They found our document very useful,” he said, noting that the meeting generated a good discussion on ways to improve primary care services and strengthen the health system, especially for communities indigenous.

Reich said that to his knowledge, this is the first time a team from the course has shared their project with the country they focused on. “The whole course aims to produce material that can be useful to health system decision-makers, connecting theory and classroom work with practice,” he said. “The Indonesian team took this idea and implemented it. It’s wonderful.

Sun Kim, PhD ’25, course instructor, said, “I could clearly sense Richard and his team’s strong commitment to serving marginalized populations in Papua. Their health reform proposal stood out for its unwavering focus on health equity and its cultural sensitivity, rooted in a deep understanding of the history of Papua and the communities it seeks to serve.

Since completing the course, Kowel has begun an internship with UNICEF to document health system reform in Lebanon. He is particularly interested in how the country provides primary care during armed conflict and how to strengthen the health system in a fragile state, he said. He hopes the experience will provide lessons he can apply to his future work in Papua, where a separatist movement has been in conflict with the Indonesian government since 1963.

Kowel’s recently completed final project excited him about the potential of a multifaceted approach to tackling public health issues. Public health work can become very technically focused, he said, but a broader view is needed to address the complex issues associated with a conflict context. “We need to understand the social and political situation as well as the values of the community and integrate them into our practices,” he said.