The world’s oceans are on the brink of major catastrophe if controversial plans to launch deep-sea mining in international waters go ahead as early as next year, an expert has warned.

Dr Sandor Mulsow, a Chilean professor of marine geology, says the risky practice could have disastrous impacts on the environment and future generations, saying more time and research is urgently needed.

“We are very concerned about deep sea mining activities in areas beyond national jurisdiction,” Mulsow told news.com.au.

“As with landmines, it will destroy (the site where you are mining), so in this case, the deep sea. »

Deep sea mining, which is still in its experimental phase, is the process of extracting valuable mineral deposits, such as copper, nickel, zinc and rare earth elements, from the seabed to depths greater than 200 meters.

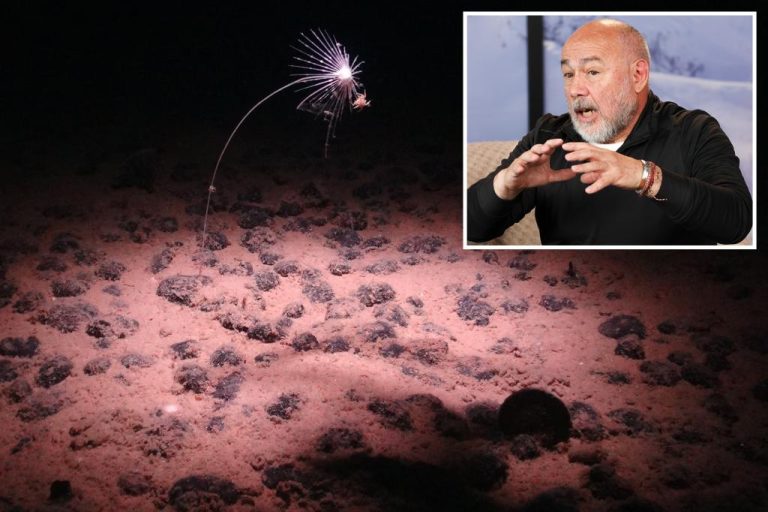

Mining companies want to expand into a vast, mineral-rich plain of international waters between Hawaii and Mexico known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ).

According to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, international waters do not belong to a single country, but rather are considered the “common heritage of mankind”.

At this point, 17 deep-sea mining contractors hold exploration contracts in the CCZ, which spans more than three million square kilometers of the Pacific Ocean, equivalent to the size of India.

Mining activity could begin as early as next year, with member states of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) – the UN-affiliated deep-sea mining regulator – aiming to finalize regulations for to deep-sea mining by July 2025.

“People just want to make money… like the mining company and an investor who thinks there will be a huge return on investment,” Mulsow warned.

“(But) it is an unthinkable and unhealthy decision for the whole world.”

The risks of deep sea mining

Research watch Deep sea mining would have a destructive impact on the ecosystems and biodiversity of the oceans, which support more life than anywhere else on Earth.

The deep-sea mining process generates plumes of previously untouched sediment, releasing CO2, at a time when the world is grappling with a customer crisis.

“The sea floor is the largest sink for CO2 and it is stored in sediments. So if we go into deep water for deep sea mining, we will destroy that interface between water and sediment, which is very old,” Mulsow said.

“Even if you disturb 10 or 20 centimeters of the seafloor, it doesn’t seem like much (but), you’re disturbing geological records that are 10 to 20,000 years old.”

Mulsow said experiments have already proven that mining small areas of the seabed causes serious long-term damage.

“We have conducted at least 19 different experiments in parts of the deep sea, in which scientists went from land with a plow and specifically disturbed the sediment in small areas one meter wide. And there has been no recovery for 30 years after this little disruption,” he said.

“Each mine will span 3,000,000 square kilometers and absorb sediment 10 to 20,000 years old, (so) life will never return.”

Why some think deep sea mining is valuable

On the other side of the debate, some believe that deep-sea mining is necessary to meet the need for critical minerals, with proponents arguing that land-based sources do not provide enough minerals needed for “green technologies” such as wind, solar and battery power.

But according to the Deep Sea Conservation Coalitionit is “not necessary” to search the seabed to find minerals.

“Scientific analysis and new developments in the electric vehicle (EV) and battery sectors show that deep sea mining is not necessary to move to net zero emissions by 2050, despite many projections indicating that the demand for minerals will increase in the coming years. » he notes in a 2023 report.

The director of the Scientific Advisory Board of the European Academies also note Deep sea mining will not provide many of the essential materials needed for a green transition.

Instead, Mulsow suggests that humanity should move toward exploiting more abundant elements such as hydrogen, rather than supporting a society that uses scarce products.

“(Some) create the feeling that what is wanted and what we need are the same, so they create a false idea that the sea has this precious wealth and that it will solve the problems,” he said. declared.

“But is the deep sea environment really necessary or is it an opportunity to create new start-ups?

The future of the oceans

If mining is allowed on a commercial scale, Mulsow warns that one of the impacts will be ocean acidification – a reduction in ocean pH over a prolonged period of time.

Also called “osteoporosis of the sea,” acidification can eat away minerals used by marine life to make shells and could affect humans in terms of food security.

“If we want to destroy the ability of seawater to support life, then we are in big trouble,” he said.

That’s why Dr. Mulsow and other scientists are calling for a moratorium (an official pause on deep-sea mining) so that more research can be conducted.

However, Mulsow goes a step further than some and calls for a moratorium for an extended period of 30 years.

“(We need) a 30-year moratorium, not 10 years, in order to fully understand what will happen if we intervene… that needs to be explored first,” he said.

Norway suspends deep sea mining projects

Earlier this month, Norway suspended plans to begin granting licenses for deep-sea mining next year, which has been opposed by environmental groups and international institutions, a party allied with the center-left government.

Norway, Western Europe’s largest oil and gas producer, had planned to become one of the first countries in the world to grant rights to tens of thousands of square kilometers (miles) of seabed.

But the small Socialist Left Party said it blocked the move in exchange for supporting the minority government’s 2025 budget.

“There will be no announcement of exploration rights for deep sea mining in 2024 or 2025,” the party said in a statement.

The Energy Ministry did not immediately comment on the decision. But Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Stoer said it was just a postponement. “We should be able to accept it,” he told TV2 television.

Parliament in January approved granting mining rights to some 280,000 square kilometers (108,000 square miles) of seabed.

The Energy Ministry then compiled a list of areas covering around 38% of this area in the Norwegian Sea and Greenland Sea that would be sold in 2025.

Norway had argued that it did not want to depend on China for minerals essential to renewable energy technology.

She believes its continental shelf contains copper, cobalt, zinc and rare earths. All of these are necessary for the production of batteries, wind turbines, computers and cell phones.

What the public can do

To help raise awareness of deep sea mining, Mulsow appeared in the award-winning 2023 documentary, Deep rise.

The documentary, narrated by Aquaman star Jason Momoahighlights the need to protect the seabed from mining companies and the operation of the ISA.

Mulsow said he hopes those who watch the documentary will understand that international waters belong to everyone and join the fight to protect them.

“It belongs to me, it belongs to you. This will belong to my children and my children’s children,” he said.

“I have not signed any document stating that Sandro Mulsow authorizes the mining company to carry out infiltrative offshore mining in its common heritage of humanity.”

The documentary inspired a global impact campaign called Deep riseled by Sydney-based advertising agency Emotive, which has designed a way for people to “reclaim the seabed from mining companies keen to turn the largest living space on the planet into the largest mining site on the planet” .

The “World’s Largest Ocean Conflict” campaign, launched last month, divided the seabed into 8.17 billion GPS coordinates – one for every person on the planet – and mapped them onto the currently claimed seabed. for mining.

“By claiming your details, as it is your birthright, you agree to protect the seabed in the name of humanity,” Emotive said.

As the possibility of commercial deep-sea mining approaches, Mulsow wants to send the positive message that those who oppose it have the power to do something about it before it starts.

He urged them to create change by electing people and parties to power who take a stand against this destructive practice.

“The people they listen to must understand that it is not a story that goes beyond them, it is their own reality. It is the common heritage of all kinds. It belongs to all species that live on this planet

– With AFP