Scientists have identified unique subtypes of fat cells in the human body, and by detangling their functions, they have found that cells can play a role in obesity.

Research, published on January 24 in the journal Nature geneticscould theoretically open avenues to new therapies to alleviate the downstream effects of obesity, as inflammation Or Insulin resistancesaid scientists.

“Finding these (big) subtypes is something very surprising”, co-author of the study ESTE YEGER-LOTEMProfessor of IT biology at Ben Gurion University of Negev, told Live Science. “This opens all kinds of potential future work.”

The results suggest that fat cells “are more diverse and more complex than we thought before”, ” Daniel BerryProfessor of nutritional sciences at Cornell University who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email.

In relation: Fat cells have an obesity “memory”, the results of the study

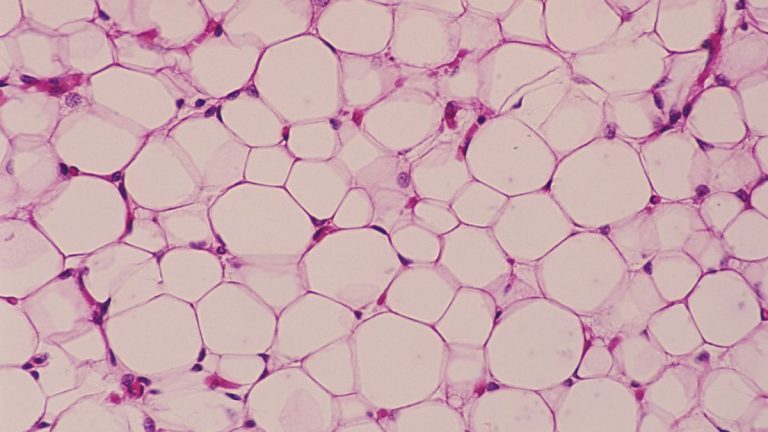

In recent decades, research has shown that adipose tissues are much more than simply store excessive energy in the body. For example, fat cells, also called adipocytes, and immune cells work together to communicate with the brain, muscles and liver. This, in turn, helps to regulate appetite, metabolism and body weightAnd it is also involved in related diseases.

“If something is wrong there”, in the adipose tissue, “it affects other places in the body,” said Yeger-Lotem.

Not all fats are created equal

Scientists have also long known that excess fat transport has been linked to a risk of health problems. However, one of the many aspects of obesity that have left perplexed scientists is that not all fats are created equal.

Visceral fat – fat cells residing in the abdomen near internal organs – is linked to a greater risk Various health problems that fat under skin, called subcutaneous fats. For example, excess visceral fat has an increased risk of heart attack,, strokeDiabetes, insulin resistance and liver disease. Studies too Suggest that visceral fat is more “pro-inflammatory” than subcutaneous fat, which could potentially contribute to poor health related to obesity.

To better understand what could happen inside fat tissues, Yeger-Lotem and his colleagues have drawn a “cellular atlas” of Adipocytes as Part of the Human Cellular AtlasA global project that aims to map all cells in the human body.

The researchers built this card using the sequencing of the unique nucleus RNA (SNRNA SEQ), which measures which genes are active and to what extent looking at RNAA molecular cousin of DNA. RNA molecules act as protein plans, commuting from the instructions of DNA In the nucleus of the cell to its protein construction sites. By measuring the RNA in the nuclei of the cells extracted from the adipose tissue, the team gathered clues on what each cell does inside the tissue.

Yerger-Lotem and his colleagues examined samples of subcutaneous and visceral fats collected from 15 people during elective abdominal surgeries. Most adipocytes were quite “classic” – which means that excessive energy storage was their main objective. But a small proportion of fat cells was “not classic” because their RNA suggested that they exercised functions not generally associated with fat cells.

Among these cells, there were “angiogenic adipocytes”, which transported proteins usually used to promote the formation of blood vessels; “Immunity adipocytes”, which make proteins linked to the functions of immune cells; And “Adipocytes of the extracellular matrix”, which are linked to scaffolding proteins which help support the structures of the cells. These cell subtypes, found in visceral and subcutaneous fat, were also confirmed under a microscope.

This “cutting edge application” of Snrna Seq suggests that these cells can play a role in the “reshaping” of adipose tissues, Niklas MejhertProfessor of endocrinology at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. Remodement here refers to how fat tissues change in response to weight fluctuations or metabolic changes. “Healthy” reshaping would help maintain metabolic balance, but if it is deregulated, it could stimulate inflammation and other poor health engines in obesity, said Mejhet.

In relation: In a 1st, scientists have reversed type 1 diabetes by reprogramming a person’s own fat cells

The study also identified the differences in the types of cells newly described according to the tissue from which they were taken. Unconventional visceral fat adipocytes seemed more likely to communicate with the immune system than those found in skin fat, said Yeger-Lotem. This link with immune cells suggests that cell subtypes could play a role in triggering the pro-inflammatory nature of visceral fat, which could help explain why belly fat is worse for health.

The data also suggested that fatty tissue donors with higher insulin resistance tended to have a higher concentration of these unconventional cells in visceral fats than people with lower insulin resistance. However, Mejhert noted that the authors had not proven causality, so it is not clear if the cells could lead to insulin resistance in any way. It is too early to find out.

If these subtypes of fat can be linked to human diseases, understand how they work could “help us fight against inflammatory processes,” said Yeger-Lotem. This could potentially help doctors predict the risk of insulin resistance in people with obesity, assuming that all points connect, she added.

Berry warned that the study used a relatively small sample size and that in this stage, it only suggests rather than demonstrating definitively that fat cells have these unusual functions. However, “these ideas highlight the importance of understanding the unique behavior of fat deposits to develop targeted treatments for obesity and related diseases,” he said.

This article is for information only and is not supposed to offer medical advice.