Why empires fall is a question that fascinates many. But in the search for an answer, the imagination can run wild. Suggestions have emerged in recent decades attributing the rise and fall of ancient empires such as the Middle Kingdom. Roman Empire has climate change And disease. This sparked discussions about whether “536 was the worst year to be alive”.

That year, a volcanic eruption created a veil of dust that blocked the sun in certain regions of the world. This, combined with a series of volcanic eruptions over the following decade, would have caused a decrease in the global temperature. Between 541 and 544 there was also the first and most serious documented event of the Justinianic plague in the Eastern Roman Empire (also called Byzantine Empire), during which millions of people died.

Studies show that there is no textual evidence of the effects of the dust veil in the Eastern Mediterranean, and that there is in-depth debate on the extent and duration of the Justianic plague. But despite this, many in academia argue that climate change and the plague epidemic were catastrophic for the Eastern Roman Empire.

Our researchpublished in November, shows that these claims are incorrect. They come from isolated discoveries and small case studies projected across the entire Roman Empire.

Using large datasets from vast territories previously ruled by the Roman Empire presents a different scenario. Our results reveal that there was no decline in the 6th century, but rather a new record in population and trade in the eastern Mediterranean.

Related: Why did the Roman Empire split in two?

We used micro- and large-scale data from various countries and regions. Microscale data included looking at small regions and demonstrating when the decline in that region or site occurred. Case studies, such as the site of the ancient city of Elusa in the northwestern Negev Desert in present-day Israel, have been re-examined.

Previous research states that this site declined by the mid-6th century. A carbon-14 reanalysis, a method of verifying the age of an organic material object, and ceramic data used to date the site showed that this conclusion was incorrect. THE the decline has only just begun in the 7th century.

The large-scale data included new databases compiled from archaeological finds, excavations and shipwrecks. Survey and excavation databases, consisting of tens of thousands of sites, have been used to map general changes in the size and number of sites for each historical period.

The shipwreck database showed the number of shipwrecks for each half century. This was used to highlight the changing volume of naval trade.

Changes in naval trade (150-750)

Our results showed that there was a strong correlation in the archaeological record from many regions, spanning today’s Israel, Tunisia, Jordan, Cyprus, Turkey, Egypt and Greece. There is also a strong correlation between different types of data.

Both small case studies and larger data sets have shown that there was no decline in population or economy in the Eastern Roman Empire in the 6th century. In fact, there appears to have been an increase in prosperity and population. The decline occurred in the 7th century and therefore cannot be linked to sudden climate change or the plague that occurred more than half a century earlier.

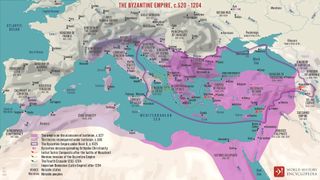

It appears that the Roman Empire entered the 7th century at the height of its power. But Roman miscalculations and failure against their Persian adversaries sent the entire region into a downward spiral. This weakened both empires and allowed Islam to rise.

This is not to say that there was no climate change during this period in some parts of the world. For example, there was a visible change in material culture and a general decline and abandonment of sites throughout Scandinavia in the mid-6th century, where this climate change was more widespread.

And the current climate crisis is poised to cause far greater changes than those seen in the past. The radical departure from historical environmental fluctuations has the power to irreversibly change the world as we know it.

This edited article is republished from The conversation under Creative Commons license. Read the original article.