Pat Murphy and I seated his kitchen table one night in February. We talked a bit about baseball and a lot of life, which is common in conversations with the 2024 Manager of the National League of the Year.

Murphy had welcomed our team of MLB network features in his world for a day, in the middle of the preparations for his second season as a manager of the Brewers. We drove in Murphy’s SUV to a spring training game. We interviewed his 10 -year -old son, Austin, while brewers and giants played Scottsdale. We visited the home of the Phoenix family to observe the Wiffle Ball game – equal to carefree and competitive – which Murphy organizes for his sons and their friends.

While the hours and the stories passed, I felt the burden of realizing how the narration of Murph would not make the final cup for the feature film which is broadcast Wednesday as part of our cover of the opening day.

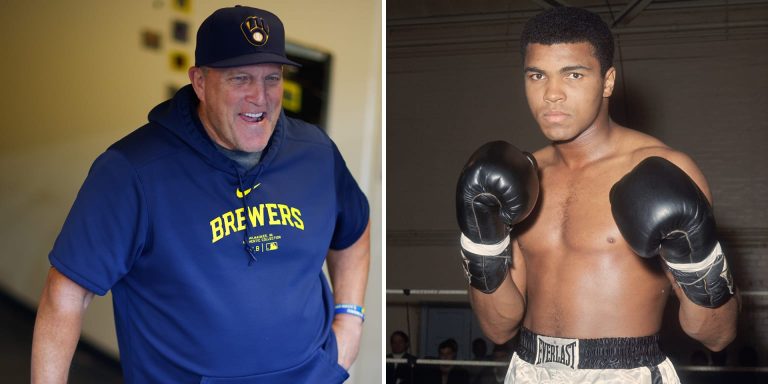

And it was before Murphy started talking to me about his friend, Muhammad Ali.

Yes. Her friend Muhammad Ali.

As it is typical of a story of Murphy, the anecdote Ali includes entries of different chapters of his life and reflects the perspective he has acquired over the years.

Murphy met Ali for the first time during a banquet in 1992, during his mandate as a baseball trainer in Notre Dame. Ali lived near South Bend to Berrien Springs, Michigan, Joe Kernan, the former mayor of South Bend, Governor of Indiana and former Baseball Student of Notre-Dame, knew Murphy’s passion for boxing and arranged to sit near “the biggest”.

Long after Murphy left South Bend to chair a power program at Arizona State, one of his former assistant coaches contacted. A high school ball player in Niles, Michigan, sought to get in touch with university coaches. He was not a candidate for the ASU. He just wanted an opportunity somewhere.

Murphy likes calls like that. If you are hungry, it has time for you. Murphy checked with his contacts in junior colleges and found a list place. Word returned to Niles that Murphy – a single father with a frantic schedule and a generous heart – had taken the time to help.

Unbeknownst to Murphy, the young man was a friend and baseball teammate of Asaad Ali at Niles High School.

Yes, Asaad is the son of Muhammad and Lonnie Ali.

“Lonnie understood that I got into four to help this child, without (agenda), and it worked for the child,” said Murphy. “He played and did very well,” said a professional contract.

“Lonnie calls this coach and says:” I want to meet this guy “.”

Lonnie had no way of knowing that “this guy” – Murphy – was a longtime boxer who venerated her husband and had a portrait of Ali in her living room. It turned out that Muhammad and Lonnie also had a house in the Phoenix region, not far from Murphy.

“Lonnie stretched out my hand, comes to my house and sees the champion up there,” recalls Murphy. “She knows that I did not know that she was going to enter my life. She says: “You have to meet the champion”. “

“Talk about luck,” said Murphy. “We looked through books together, photos of him. It was invaluable. I always respected that he was not afraid to go against the grain, was not afraid to be himself.”

At that time, Parkinson’s disease had made it difficult to communicate all areas. But Murphy has a living memory of the initial conversation they had at the South Bend banquet in 1992.

Murphy remembers asking Ali: “Field, why did you start to boast, talk, run your mouth, all this kind of thing?” Were you still like that? “

Murphy pruned his voice barely more than a whisper, telling me what happened next.

“He looked and said,” I was afraid to death “. This is what he said: “I was afraid to death”, and it just came out.

“I say to myself,” wow “. You will never hear him say that.

Ask a American sports fan to appoint the most intrepid athletes of the last 100 years, and Ali would be one of the most popular answers.

I observed in Murphy that if Ali was afraid, then everyone should have the grace to be afraid.

“Exactly – because we are all,” replied Murphy. “Who are we kidding?” Fear is one of them. If you learn to use it, like fire, you can do a lot of big things. If you don’t learn to use it, it can burn your home and destroy you.

“He taught me a lot, just by this type of thing.”

The memorable exchange of Murphy with Ali performed more than 30 years ago, at a time when Murphy – by his own admission – was too obsessed with victories and losses during the successful mandates of Notre Dame and Arizona State.

“People told me that I was an excellent coach,” he said. “I am here to say to you: I was not … I was so intense. I was so motivated … It was I who did not understand this intensity, or this franchise with the players, I was not good. I know that now … It was tearing me inside, because it was me.”

During these years, the fear that Murphy allowed himself to recognize the loss of baseball matches. His point of view is different now, thanks to years of reflection, advice and journalization he makes at home. Murphy attributes to his fire sessions Harvey A. Dorfman, a pioneer in sport psychology, for having helped him “reach these places with which I had so much help”.

I asked Murphy what still scares him now.

“Many things, guy,” he replied. “Many things. I want to be here for my children. I want my health to be good … I want to see them go a little further. It’s important for me.”

Murphy, 66, underwent a heart attack during a training session of the Brewers team in 2020; Less than four years later, after the departure of the close friend Craig Counsell, he was the club manager on the day of the opening.

The series of events helps to explain why Murphy found a greater contentment in his personal life – and baseball. He prioritizes time with Austin and his 5 -year -old son, Jaxon. He speaks with pride of Kai, 24, who worked on his diploma in Arizona State even during training in the spring.

And Murphy almost cried when I asked questions about his daughter, Keli, who is married to the old MLB All-Star Pedro Alvarez and has two children. Murphy has a narrower relationship with Keli now than while she was growing up.

Keli enrolled in university at Arizona State after Murphy received Kai’s unique custody when his son was 3 years old.

“It’s my best friend in the world,” Murphy told me. “She didn’t grow up in this life. She came to the ASU University and helped me raise Kai, because I didn’t know what I was doing. ”

Now Keli returns to the University herself to become certified as an advisor. I asked Murphy if he considered this call as Keli’s own form of coaching.

“You see, you smothered me on this subject,” he said. “She is the biggest. And I know it’s my daughter, but if you spend time with her, she understands. She gets it, and I think this (baseball) world helped her reach her.

“Her husband being in the company, passing by everything he experienced – Silver Slugger and All -Star, not as long a career (of play) as he wanted. Learn what she learned from all this, she is so clear.

“Yeah, she is in training. And she is great – much better than I could never dream, because she is sensible, she has a level. She has an element of intensity but an element of grace. I am so proud.”

When Murphy built his stadium developed from the backyard, he gave him a poignant name: Bob Welch Field, after the winner of the Cy Young Award who fought against dependence and Died in 2014 at the age of 57. Murphy, whose deceased father treated alcoholism, hired Welch to work on his ASU coach staff.

“He was a great friend,” said Murphy. “He taught me a lot about the baseball game. He taught me the major league match. He taught me coaching, the treatment of people (good), the lighter side. He was a man so giving … I always want to honor him. When everyone arrives, we can bring their name. We are doing it now.

“Everyone has someone who has a dependence in their life. It is much more serious if you do not understand it or if you have not experienced it. I learned it a lot. It is a horrible thing. … My older children knew him well and loved him. He was so good for them. He was so open with them and spoke to them openly for all this. It was a great education for my children.”

Welch’s influence has helped Murphy realize that authenticity is often the best response to complexity. This lesson helps to explain why Murphy, in his seventh decade of life, describes himself as a “work in progress”. Murphy knows more than him as a young coach to Notre Dame, but he is less certain of the answers. He added humility without losing charisma, a combination that helps his players manage the stress of a sports focused on failure.

He wants to lead them to a World Series title. Of course, he does, but Pat Murphy realized that the best way to continue the big dream is to focus on the smallest.

“It may seem crazy, but I don’t even think of (the World Series),” said Murphy. “I really don’t do it. Whatever happens, we work there. We work there.

“I believe that 2024 reinforced the things I knew I was true in the game. It’s a game on people. I am absolutely for the analysis. I am absolutely for data. I want this data. I want to understand it, so I don’t care. I use it.

“But the game is played by people and will always be. The mentality of these people – these hungry players – made me seem well for a long time.”