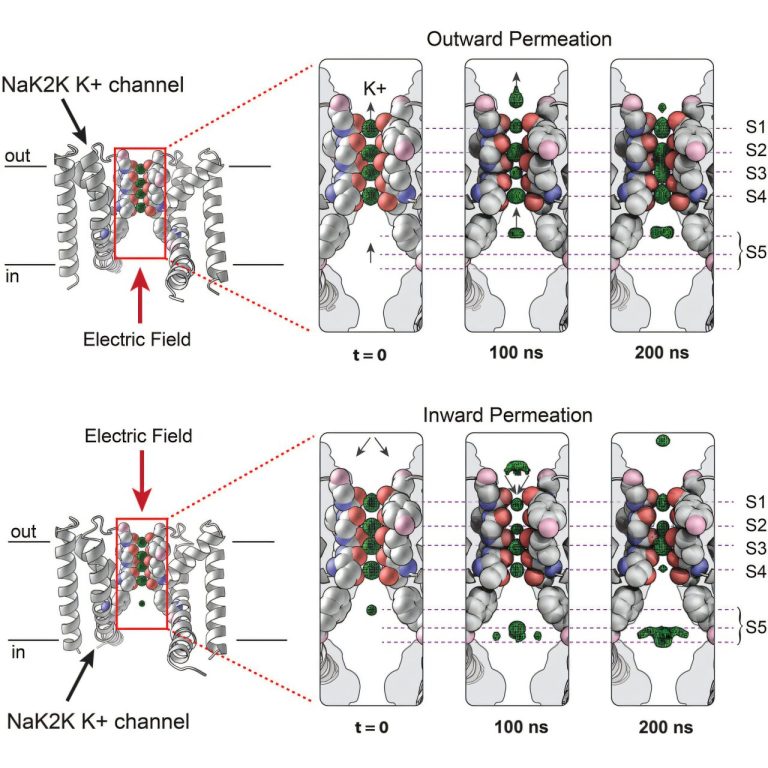

Graphic summary. Credit: Cell (2025). DOI: 10.1016 / J.Cell.2024.12.006

Scientists have made enormous progress in understanding protein structures in recent decades. Imaging technologies such as cryo-electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography help researchers visualize protein forms in unprecedented details; However, these tools mainly produce static snapshots of molecules. To really understand the protein function, researchers must see them in action.

Researchers from the National Laboratory of the University of Chicago and Argonne have been working on this problem for years; Now, with partners from Harvard University, they have perfected a new technique to create experimental moving films in motion.

In a newspaper published in CellThey demonstrate the method, called X -ray crystallography resolved with stimulated electric field (EFX), on a Potassium ion channelA pore in the cell membrane which regulates the movement of potassium in and outside the cells.

The resulting videos have confirmed the results of other research in the past 25 years using much more meticulous biochemical approaches, showing that the EFX can be a new powerful tool for visualizing and quickly understanding protein dynamics.

“The fundamental problem is that we have never had methods for simple experiences to see the proteins in motion, because the proteins are really small and that they move very quickly,” said Rama Ranganathan, PH.D., one of the main authors of the new study.

“But the future of structural biology will be to look at the mechanics or dynamics of molecules. So I think what we have done here is to provide a technology that can bring us.”

The magical experience

Ranganathan, who is a professor of Joseph Regenstein in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering in Uchicago, started this work when it was at the University of Texas Southwestern medical center. In 2016, his team published an article in Nature First of all describing How they used an electric field to move the proteins while they were capturing images using crystallography resolved over time.

This approach takes the crystallized version of the protein of interest and the place on the path of an X -ray beam. When the X -rays hit the crystal, they are dispersed in many directions, producing models which can be analyzed to produce the complete three -dimensional shape.

The “resolved” part of this technique means that they take continuous images of the protein because it undergoes structural changes, capturing it in motion.

“It was the magical experience we all expected,” said Ranganathan, but the process was difficult and long.

He moved to Uchicago in 2017, largely for the opportunity to direct the installation of biocars, which gives access to advanced X -ray technologies using the source of advanced photons at the National Laboratory of Argonne.

His team continued to study the protein dynamics, among others, working with the other author of the new study, Doeke Hekstra, Ph.D., former post-doctorant of the Ranganathan Laboratory who is now an associate professor of molecular and molecular and cell biology and physics applied to Harvard.

By perfecting EFX technology, they focused on studying the potassium ion channel, a fundamental cellular structure involved in a multitude of biological processes. It is important to note that the activity of the ion channel is initiated by applying an electric field to move the ions through the pore. In this way, the team could manipulate the action experimentally to record the activity it wanted to see.

While they followed the ions crossing the canal, they also saw unique mechanical characteristics of the work channel which corresponded to different observations collected over the years by other researchers.

The difference is that these scientists had to use long methods and with high intensity of workforce as induire Genetic mutations To manipulate the channels, while EFX was able to capture the activity of the ion channels in a neat video.

“During the scale of some nanoseconds, we could see ions crossing the pore of this canal,” said Ranganathan. “All these 25 years of knowledge, we were able to see it in the dynamics of a channel during its operation.”

The objective is to integrate these dynamic observations with calculation models to improve engineering and protein design. Ranganathan is already deeply involved in the use of AI to design and build new personalized proteins, through its Epozyne biotechnology company.

Its platform simulates and learns models of millions of years of evolution to create new proteins for specific purposes, such as antibodies to treat the disease or to capture carbon to minimize industrial emissions. Detailed video images of protein in action – real or simulated – could be incorporated into these models to refine and improve these conceptions.

“We could create a virtuous cycle between calculation prediction and experience, so that we can refine our simulations to the point where they really look like experiences,” said Ranganathan.

“Once we have triggered the simulations on all the molecules where people have resolved the structure, we could build a dynamic database with which we can really make predictions for calculating all proteins in action.”

More information:

Boram Lee et al, direct visualization of the ion conduction stimulated by the electric field in a potassium channel, Cell (2025). DOI: 10.1016 / J.Cell.2024.12.006

Supplied by

Medical Center of the University of Chicago

Quote: The new X-ray technology capture of moving proteins (2025, February 28) Extract on March 1, 2025 from https://phys.org/news/2025-02-ray-technology-captures-proteins-mtion.html

This document is subject to copyright. In addition to any fair program for private or research purposes, no part can be reproduced without written authorization. The content is provided only for information purposes.