The “brazen and targeted” killing of health insurance executive Brian Thompson, CEO of UnitedHealthcare, outside a New York hotel this week shocked America. The reaction to the crime also revealed latent anger against a trillion-dollar industry.

“Prior authorization” does not seem like a phrase likely to arouse much passion.

But on a hot day last July, more than 100 people gathered outside UnitedHealthcare’s Minnesota headquarters to protest the insurance company’s policies and denial of patient claims.

“Prior authorization” allows companies to review proposed treatments before agreeing to pay for them.

Eleven people were arrested for blocking a road during the demonstration.

Police records indicate they came from across the country, including Maine, New York, Texas and West Virginia, to attend the rally organized by the People’s Action Institute.

Unai Montes-Irueste, director of media strategy for the Chicago-based advocacy group, said protesters have personal experience with denied requests and other problems with the health care system.

“They are denied care and then they have to go through an appeal process that is incredibly difficult to win,” he told the BBC.

The simmering anger many Americans feel toward the health care system – a dizzying array of providers, for-profit and nonprofit corporations, insurance giants and government programs – came to light after the apparently targeted killing of Thompson in New York. Wednesday.

Thompson was the CEO of UnitedHealthcare, the insurance unit of healthcare provider UnitedHealth Group. The company is the largest insurer in the United States.

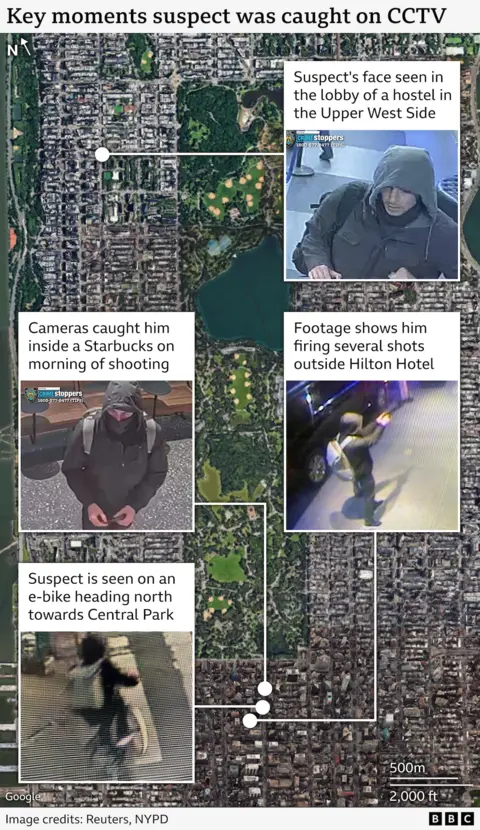

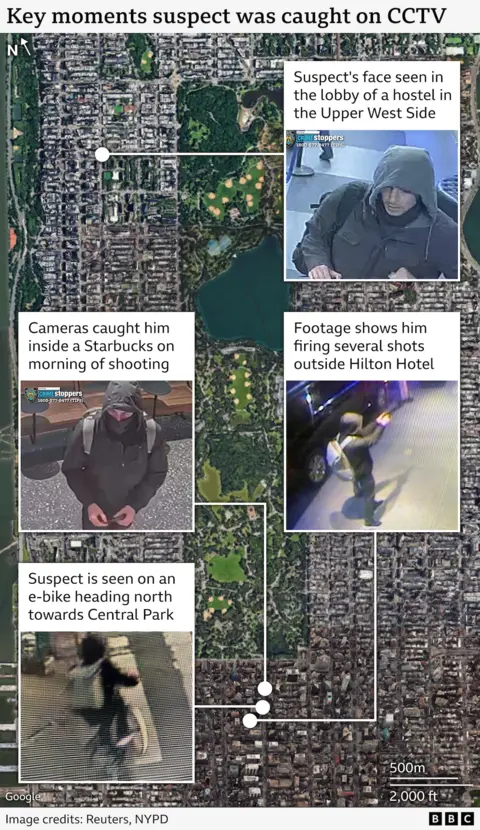

Police are still searching for the suspected killer, whose motives are unknown, but authorities have revealed messages written on shell casings found at the scene.

The words “deny,” “defend” and “depose” were discovered on the boxes, which investigators believe could refer to tactics that critics say insurance companies use to avoid payments and increase claims. profits.

A scroll through Thompson’s LinkedIn history reveals that many were angry about the denied claims.

A woman responded to a post by the executive bragging about her company’s work to make medicine more affordable.

“I have stage 4 metastatic lung cancer,” she wrote. “We just left (UnitedHealthcare) because of all the denials of my medications. Every month there is a different reason for the denial.”

Thompson’s wife told US broadcaster NBC that he had already received threatening messages.

“There have been some threats,” Paulette Thompson said. “Basically, I don’t know, a lack of (medical) coverage? I don’t know the details.”

“I just know he said some people were threatening him.”

A security expert says frustration with high costs in many industries inevitably leads to threats against business executives.

Philip Klein, who runs the Texas-based Klein Investigations, which protected Thompson during his speech in the early 2000s, said he was surprised the executive didn’t provide security for his trip to New York.

“There is a lot of anger in the United States of America right now,” Mr. Klein said.

“Companies need to wake up and realize that their leaders can be hunted anywhere.”

Mr. Klein says he has been inundated with calls since Thompson’s death. Large American companies typically spend millions of dollars on the personal security of their top executives.

Following the shooting, a number of politicians and industry officials expressed shock and sympathy.

Michael Tuffin, chairman of insurance industry organization Ahip, said he was “heartbroken and horrified at the loss of my friend Brian Thompson”.

“He was a devoted father, a good friend to many and a refreshingly candid colleague and leader.”

In a statement, UnitedHealth Group said it had received many messages of support from “patients, consumers, healthcare professionals, associations, government officials and other caring individuals.”

But online, many people, including UnitedHealthcare customers and users of other insurance services, reacted differently.

These reactions ranged from sharp jokes (a common quip was “thoughts and prior authorizations,” a play on words “thoughts and prayers”) to comments about the number of insurance claims rejected by UnitedHealthcare and other companies.

At the extreme, industry critics have made it clear that they have no pity for Thompson. Some even celebrated his death.

Online anger appears to be bridging the political divide.

Animosity has been expressed from avowed socialists toward right-wing activists wary of the so-called “deep state” and corporate power. It also came from everyday people sharing stories of insurance companies denying their claims for medical treatments.

Mr. Montes-Irueste, of Popular Action, said he was shocked by the news of the murder.

He said his group campaigned in a “non-violent and democratic” way, but added that he understood the bitterness online.

“We have a balkanized and failing health system, which is why very strong feelings are being expressed right now by people who are experiencing this failing system in different ways,” he said.

Mr. Tuffin, president of the health insurance trade association, condemned all threats made against his colleagues, describing them as “mission-driven professionals working to make coverage and care as affordable as possible.”

These messages underscore the deep frustration many Americans feel with health insurers and the system in general.

“The system is incredibly complicated,” said Sara Collins, a senior researcher at the Commonwealth Fund, a health care research foundation.

“Just navigating and understanding how you are covered can be a challenge for people,” she said. “And everything may seem good until you get sick and need your plan.”

A recent Commonwealth Fund study found that 45% of insured working-age adults have been charged for something they thought should be free or covered by insurance, and less than half of those who have reported errors alleged billing disputes. And 17% of those surveyed said their insurer had denied coverage for care recommended by their doctor.

Not only is the U.S. health care system complicated, it is expensive, and enormous costs can often fall directly on individuals.

Prices are negotiated between providers and insurers, Collins says, meaning that what is charged to patients or insurance companies often bears little resemblance to the actual costs of providing medical services.

“We see high rates of people reporting that their health care costs are unaffordable, regardless of insurance type, even (government-funded) Medicaid and Medicare,” she said.

“People are accumulating medical debt because they can’t pay their bills. This is unique to the United States. We truly have a medical debt crisis.”

A survey by researchers at the KFF health policy foundation found that about two-thirds of Americans believe insurance companies deserve “a lot” of blame for high health care costs. Most insured adults, 81%, still rate their health insurance as “excellent” or “good.”

Christine Eibner, a senior economist at the nonprofit think tank RAND Corporation, said that in recent years, insurers have increasingly been denying treatment coverage and using prior authorizations to deny coverage.

She said the premiums amount to around $25,000 (£19,600) per family.

“On top of that, people are having to pay out-of-pocket expenses that could easily run into thousands of dollars,” she said.

UnitedHealthcare and other insurers have faced lawsuits, media investigations and government investigations into their practices.

Last year, UnitedHealthcare settled a lawsuit brought by a chronically ill student whose story was covered by the news site ProPublica, who claims he had to pay $800,000 in medical bills when prescribed drugs by his doctor was refused.

The company is currently pursuing a class action lawsuit which claims to use artificial intelligence to end treatments sooner.

The BBC has contacted UnitedHealth Group for comment.

With reporting by Tom Bateman