Plastic pollution is one of the determining environmental challenges of our time – and some of the smallest organisms of nature can offer a surprising outcome.

In recent years, microbiologists have discovered Bacteria capable of breaking down different types of plastic, referring to a more durable path to follow.

These “plastic eaters” microbes could one day help to shrink the mountains of discharge and ocean waste. But they are not always a perfect solution. In the wrong environment, they could cause serious problems.

Plastics are widely used in hospitals in things such as sutures (in particular the type of dissolution), dressings and rolled implants. Could the bacteria found in hospitals therefore decompose and feed on plastic?

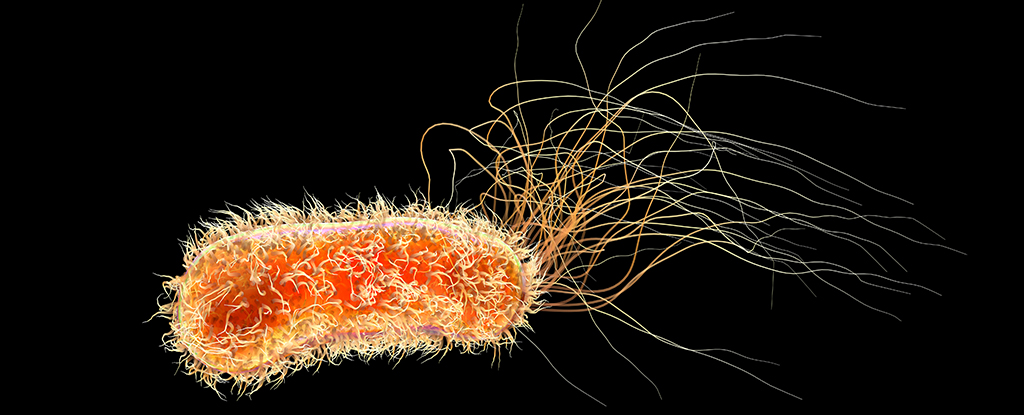

To find out, we have studied the genomes of known hospital pathogens (harmful bacteria) to see if they had the same enzymes degrading the plastic found in certain bacteria in the environment.

We were surprised to find that certain hospital germs, as Pseudomonas aeruginosacould be able to break plastic.

P. aeruginosa is associated with around 559,000 deaths worldwide each year. And many infections are picked up in hospitals.

Patients under fans or with open wounds of surgery or burns are at particular risk of a P. aeruginosa infection. Just like those who have catheters.

We decided to move forward in our computer research bacterial databases to test the capacity of plastic of P. aeruginosa in the laboratory.

We focused on a specific strain of this bacteria which had a gene to make an eating plastic enzyme. He had been isolated from a patient infected with the wound. We discovered that not only could he break down plastic, but use plastic as a food to cultivate. This capacity comes from an enzyme that we have named PAP1.

Biofilms

P. aeruginosa is considered a High priority pathogen by World Health Organization. It can form difficult layers called biofilms which protect it from the immune system and antibiotics, which makes it very difficult to treat.

Our group previously shown that when environmental bacteria form biofilms, they can decompose faster plastic. So we wondered if having a degraded plastic enzyme could help P. aeruginosa be a pathogen. Surprisingly, this is the case. This enzyme made the strain more harmful and helped her build larger biofilms.

To understand how P. aeruginosa Built a larger biofilm when it was on plastic, we separated the biofilm. Then, we analyzed what the biofilm was done and found that this pathogen produced larger biofilms by including degraded plastic in this viscous shield – or “matrix”, as we officially know. P. aeruginosa used plastic as cement to build a stronger bacterial community.

Pathogens as P. aeruginosa Can survive for a long time in hospitals, where plastics are everywhere. Could this persistence in hospitals be due to the ability of pathogens to eat plastics? We think it is a real possibility.

Many medical treatments involve plastics, such as orthopedic implants, catheters, dental implants and hydrogel pads for the treatment of burns. Our study suggests that a pathogen that can degrade plastic in these devices could become a serious problem. This can fail treatment or worsen the patient’s condition.

Fortunately, scientists work on solutions, such as the addition of antimicrobial substances to medical plastics to prevent germs from feeding on them. But now that we know that certain germs can decompose plastic, we will have to consider this when choosing materials for future medical use.![]()

Ronan McCarthyProfessor of biomedical sciences, Brunel University of London And Ruben de DiosPostdoctoral researcher, biotechnology, Brunel University of London

This article is republished from The conversation Under a creative communs license. Read it original article.