Lucy says that she was always a little disturbing, but two years ago, she started to worry about it and started to have panic attacks.

“I did not know what was going on and my parents either,” said the 15 -year -old. “It was frightening. The attacks would occur without warning. It got worse and I started to have them in public.”

Lucy began to miss a lot of school and stopped socializing. She says it was difficult for her parents to see her in difficulty. “We didn’t know what to do or where to go.”

For six months, she tried to manage her anxiety herself, but ultimately the family decided to pay a speaking therapy called cognitive behavioral therapy.

Lucy says it made a huge difference. Although she still has panic attacks, they are much less frequent and she is back to school and does the things she loves.

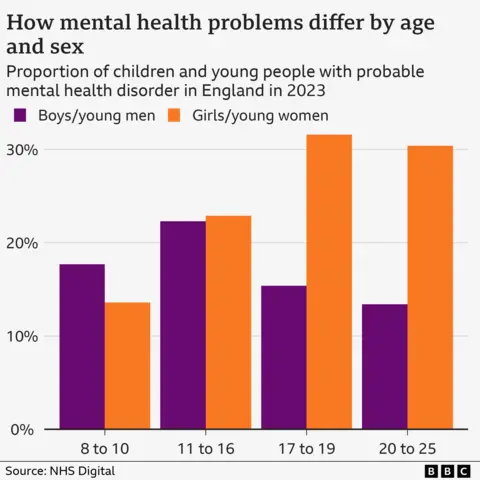

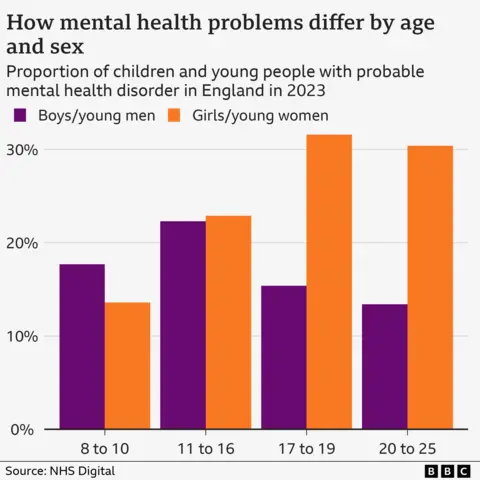

Lucy’s story is far from unique. NHS figures suggest that one in five children and young people aged eight to 25 suffers from a likely mental health disorder.

Why are the problems so common

Adolescence is when problems become increasingly common while young people present themselves to the challenges of growth, stress of exams, friendships and relationships.

There are also biological reasons that make emotional health problems more likely, explains Professor Andrea Danese, an expert in children’s and adolescent psychiatry at King’s College in London.

“The brains of adolescents do not develop in one go. The part that deals with emotions matures earlier than the responsible part of self -control and good judgment.

The Zenith, he says, is adolescence, when emotional reactions are still reinforced by hormones and changes in internal body clock which have an impact on sleep diagrams.

When and how to help

So, what constitutes normal emotional challenges-and when adolescents and their parents should be worried and consider looking for professional help?

Professor Danais says he understands why many find it difficult to judge. He considers what follows as normal teenage emotional features:

- Periodic irritability and mood

- Occasional social withdrawal or desire for intimacy

- Anxiety about social acceptance or school return

- Experience identity and independence

- Emotional reactions that seem disproportionate

About those who do not interfere with daily activities, parents should feel able to support their children, he believes.

The most common problems that the teenager experience are the weak mood and anxiety. For the low mood, says Professor Danese, maintain healthy routines around eating, sleeping, being active and staying in contact with friends and family is important, as is planning of the activities that your child loves, like travel or practice a sport.

“And help them identify, break down and try solutions for problems that can be occurred,” he adds.

For anxiety, soothing techniques are useful, he says. These can include breathing exercises, an earth, through which you focus on the environment around you and what you can see, touch and smell and mindfulness activities.

“It is important to avoid the trap of providing unnecessary comfort,” said the Danish professor. Instead, in parallel with the teaching of soothing techniques, parents should discuss and test dreaded situations. “To reduce concerns, this can help note them or talk to them about a special” worrying time “once a day.”

Build resilience

Stevie Goulding, who heads the parents’ assistance line for young minds, says anxiety is the problem they get the most calls.

“Many children will have episodes of anxiety and even panic attacks. It is difficult for parents. They can easily find themselves lacking in confidence and judgment on what to do. We receive a lot of parents’ calls in this position. When they see their child in difficulty, it can have them questioned themselves and they simply do not know where to turn.

“The main advice we give to parents is to communicate with their children. Give them permission to talk about what bothers them-and if they don’t want to talk to them, ask them if there is someone else they prefer to talk to.”

Ms. Goulding also recommends talking to your child’s school because they may have noticed things too.

But she adds: “Children must have space – avoid the temptation to rush and try to repair things. Just reflect what they say and listen.”

The child’s psychologist, Dr Sandi Mann, agrees, saying that parents have an understandable temptation to want to solve any problem that their child is confronted when it is not necessarily the best solution.

Rather, she says that parents should help teach and strengthen their children’s resilience – and have Written on this subject for the BBC.

She recommends parents:

- Explain the setbacks to everyone, giving examples of things that went wrong in your own life

- Embrace errors

- Allow them to make their own decisions, stressing that they are largely responsible for their own happiness

- Challenge their beliefs, in particular black and white thought and catastrophization

“I think we can sometimes create the impression that children and young people are unable to solve their own problems when we precipitate them to get help or turn to medication.”

Sign professional help is necessary

But Dr. Mann and Professor Danais, both parents should not hesitate to request professional support if necessary.

“There is nothing to be ashamed,” said Dr. Mann. “We just need to know when trying to solve problems and when getting help.”

They both put similar behaviors that should act as a trigger for parents to have help. These include:

- Autonomous and suicidal thoughts

- Extreme changes in food or sleep

- Dramatic personality changes and despair expressions

- Important interference with daily operation, such as going to school or socializing

- Prolonged withdrawal of activities which were appreciated in the past

Dr. Elaine Lockhart, president of the Faculty of Children and Adolescents of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, says that parents should feel comfortable managing mental health with their children and asking for help.

“We know that many children are struggling. The idea that school years are the best years of your life is a mistake.”

But with long waiting times for the mental health services of NHS children, knowing where to go for help is not easy, especially if you cannot afford private therapy.

The first call point is normally your general practitioner or your mental health support teams linked to schools in certain areas. In addition to references to NHS mental health services, they can put you in contact with local organizations and charities that can provide support.

“The schools themselves can also help – some have advisory and support services,” said Dr. Lockhart.

“But I think parents can underestimate the role they can play even if their child is waiting for support or really gets therapy or treatment. The house is where they will spend most of their time – so parents are a large part of the solution.”

If you need mental health support, the following links provide information on how to get help: