Because God quickly realized that humans were a group of thief, he established rules against the theft of one of the first things downloaded on the tablet of Moses 1500 years ago: “You will not steal . ” It is classified number four on the list of things that we are not supposed to do, so it is clear that it was important for the all-powerful: do not take things that are not yours.

Lionel Mapleson did not think he was flying. When he did what he did, that not flight. It was not until later that history marked Mapleson as the father of all musical hacks.

Mapleson came from a long line of musical librarians which can be attributed to the 1700s. Before moving from London to New York in 1889, where he hoped to become a great concert musician, his father trained him in the most ends of occupation. Fortunately, because six years later, it was clear that Mapleson was not cut to be a high -level artist. His discount position was a concert as a newly trained librarian from the Metropolitan Opera.

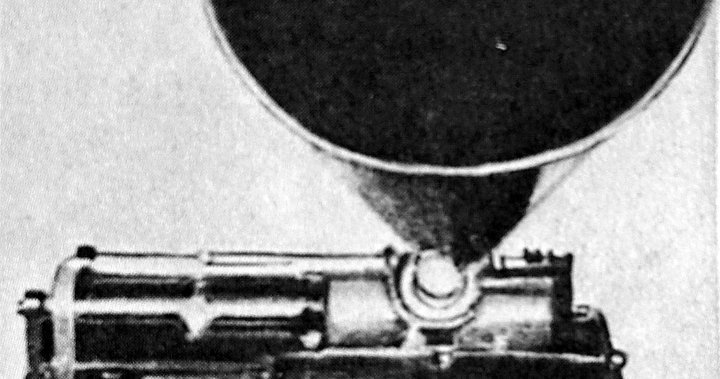

At the beginning of 1900, he bought a new Edison speaking machine – a phonograph – so that he could listen to the last thing: striped performance records in wax cylinders. A friend then recommended to buy a micro-reproductory from Bettini, a phonograph style machine which could also record the audio on cylinders four to six inch long and play them. It was roughly the size of a suitcase, so it was reasonably portable.

“Do you want perfect reproduction without resonance, cries or metal explosions?” said advertisements. “Then buy Bettini’s micro-reproductory for the clearest and strongest!” A novice can make a perfect disc! »»

The machine would soon win a gold medal for innovation at the Paris 1900 exhibition. Mapleson picked up one for $ 30 (equivalent to $ 1,000 today) on March 17, 1900.

On March 22, he wrote this in his newspaper: “For the present, I do not work properly, neither eat nor sleep. I am a phonograph maniac !! Always do or buy recordings. The Bettini device is just perfect. »»

His family got used to recording them in Mapleson at home while he was capturing audio every day, keeping cylinders and recycling others by thoroughly razing the groves. Mapleson had become one of the original audio recorders at home.

Get national news

For news that has an impact on Canada and worldwide, register for the safeguarding of news alerts that are delivered to you directly when they occur.

As a librarian and archivist, he also produced Bettini’s potential; He had the ability – and access – to record the performances of the MET scene for posterity. Then, after leaving his bosses to put know what he had planned, he got to work. On January 16, 1901, he recorded Nellie Melba in an opera entitled The cid. He installed the Bettini in the prompt box, a stand in front of the stage where someone sat down to remind the actors their lines when he failed.

But the audio he captured from this point of view was not very good, so Mapleson nested a footbridge perhaps 40 feet above the stage and the orchestra. A large horn was hung on the MET fly system – the network of strings and pulleys used to raise and reduce curtains and landscapes – to channel as much as possible towards Bettini.

Over the next two years, Mapleson has recorded dozens, perhaps hundreds of performances for two minutes at a time (it was a maximum capacity of a cylinder), keeping the good and recycling the cylinders when the concert did not live in its standards. No one complained with the exception of the occasional member of the public who was bored that the Bettini horn interfere with lines of view.

Certain Mapleson recordings were surprisingly clear given the technology of the time. Others have been stifled, cracked and hard on their ears. But they all had one thing in common: they documented music of the time in one of the most famous places in the world. He also managed to capture famous singers and conductors who have never had the chance to make an official commercial recording.

Here is a sample.

Mapleson wanted to share his experiences, often inviting singers, conductor and musicians to listen to what they had done.

Mapleson’s semi-secret recording practices suddenly ended in 1904, perhaps because someone made the commercial value of these cylinders somewhere. Perhaps it was the order demanding that their employee stops rye for himself so that he can do and sell such recordings. Perhaps some artists have complained, realizing that their talent and their work were used without their permission. Or maybe he was bored.

As he packed his machine, Mapleson had a library of perhaps 140 of these very fragile cylinders. Others have been offered in gifts or thrown away. When he died of a heart attack on December 21, 1937, no one knew what to do with it.

William Seltsam, the chief of the International Record Collectors Club, had met Mapleson earlier in 1937 and received a challenge: to do something with these exploded things. After having borrowed 124 cylinders from the family, Seltsam tinkered with things until it is able to slowly move the audio to recordings of 1O-Pouce 78 rpm.

These recordings have since been published and reissued several times, including on CD, more recently with digital techniques that have detected static and scratches.

Long lost cylinders are still occasionally appeared. Some were found in an unwanted store in Brooklyn. Others have been acquired by collectors. A couple was located in Mexico. The family, which had been sitting on around 16 cylinders for decades, gave them and around 50 journals documenting their content and other events on the life of Mapleson at the New York public library to study. They were found in a beer cooler who had lived under a tilting armchair in Long Island.

But let’s go back to the piracy issue. Was Mapleson the equivalent of someone who makes an illegal recording of a concert today? Not really, because when he did his thing, the sound recordings were not yet covered by the laws on copyright and intellectual property. The audio recording technology was so new that the legal codes had not yet recognized that making unauthorized recordings (and distribute them) as something that should be deposited under “you will not steal”. American Sound Recording Copyright laws were only resolved until 1972.

It is therefore unfair to include Mapleson in the parade of characters who took and / or distributed the music of others without their permission. He was not exactly Napster, Limewire, Pirate Bay or Megaupload, but he is definitely in the family tree.

& Copy 2025 Global News, A Division of Corus Entertainment Inc.