The projection of power is more than expected by military power – the economic power of a nation is the foundation of its capacity to project national power. And technological development is an important element of this power. By quoting his reasoning behind the Nobel Prize 1987 for the economyGiven to Robert Solow, the Committee wrote: “Technological development will be the engine of long -term economic growth.”

It is therefore up to us to seriously consider how nations should promote technological development. The basic principle of the American approach has long been for the federal government to finance basic research and to allow the commercial sector to compete to develop technologies that benefit society, create jobs and feed economic growth. But is it really so simple?

In the days which followed the Second World War, when the United States had undisputed economic power and a massive advance of technology, monopolistic companies with large research laboratories carried out not only fundamental scientific research, but also served as a star of the North which guided research towards marketing. The giant lead of American industry in technology has masked its underlying ineffectiveness in the translation of basic research in applied research. Companies have focused on improving productivity rather than improving products to make them more competitive.

The world today is very different. The economic powers bring competition on our coasts: China, India, Israel, Japan, Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, Vietnam and Europe. Some competitors are allies and partners, sharing American values; Others have different visions of the world. Be that as it may, these competitors do not wait for basic research to be carried out in technological products. They actively feed technological development and feed the progress of manufacturing and technology products. They build new supply chains and deploy their increasingly educated workforce to perfect the manufacturing process.

Without manufacturing capacityNo quantity of research and development can lead to a scale of competitive products on the market.

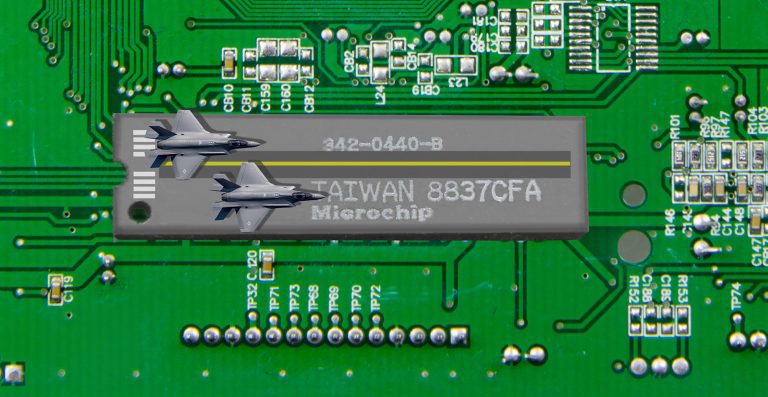

The manufacture of advanced technology products, such as semiconductor chips and batteries, is not only to produce the same thing on several occasions without change. Innovations in materials, processes and design focused by lessons learned on the manufacturing floor improve products engineering as much as the design and R&D of products.

America can continue to bring back Nobel prizes to the house, but more and more, others build and evolve the technologies activated by our inventions. The filling of the “laboratory” gap, as presented by the 2023 flea law, is essential but not sufficient. We have seen first mobilization advantages such as flat screen screens and electric vehicles move away from our hands. Supported technological leadership requires excellence in manufacturing at all levels, from components to systems. Manufacturing as a discipline itself deserves R&D and dedicated policy. It is nowhere more apparent than in the semiconductor industry.

We have already seen this story. The Puces Act is only the most recent federal initiative in a long line of efforts to ensure the example of America in semiconductors. Previous programs like VHSIC in the 1970s and Sematech in the 1980s aimed to solve the same problem. And for a while, they did it. But when attention and investment have disappeared, the gains also opened the land to our competitors.

Technological policy must therefore be approached not as a punctual solution but as a continuous commitment. This includes the development of good policies that go beyond the culture of inventions and actively encourage the inner scaling. If the invention represents 10% of the value strengthening process and a competitive advantage thanks to technology, the scaling is 90%.

Initiatives like the Municipalities of Microelectronicswhich aims to accelerate the transition from semiconductor innovation from the laboratory to Fab by building and sharing domestic prototyping facilities, are essential to success, as are the training and recycling programs of the national workforce required for scaling. The creation of an environment of favorable scaling thanks to the deliberate construction of ecosystems, including the judicious application of export and import controls, to reward the scaling with tax credits for special use and the abolition of regulations over Budget is also critical success facilitators, just as the measurement of the scale works- course.

This is particularly difficult in the United States, where the default instinct is to let the market decide. But the market does not optimize long -term strategic results – it prioritizes short -term profits. In mature industries such as the manufacture of cars or chips, the emphasis is placed on efficiency and margin; In more recent industries such as technological conception, emphasis is placed on revolutionary innovation. The two are necessary, but the incentives diverge.

In the global competition for technological leadership, which often separates losers winners, it is the determination of the government to use all the tools available to create and feed the invention and scale ecosystems. This is the strategic challenge to come.

Victoria Coleman was chief scientist of the Air Force during the Biden Administration and director of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) during the first Trump administration. She is now CEO of Acubed and responsible for research and technology for Airbus North America. HS Philip Wong is a professor of electric engineering at the University of Stanford and former vice-president of business research in TSMC, the largest semiconductor foundry in the world.