Find a better way

Whenever a Amsterdam resident requests social benefits, a social worker reviews the request for irregularities. If a request seems suspicious, it can be sent to the city’s investigations department – which could lead to a rejection, a request to correct the paperwork errors or a recommendation that the candidate receives less money. Investigations can also occur later, once the advantages have been dispersed; The result may oblige beneficiaries to reimburse funds and even put certain indebtedness.

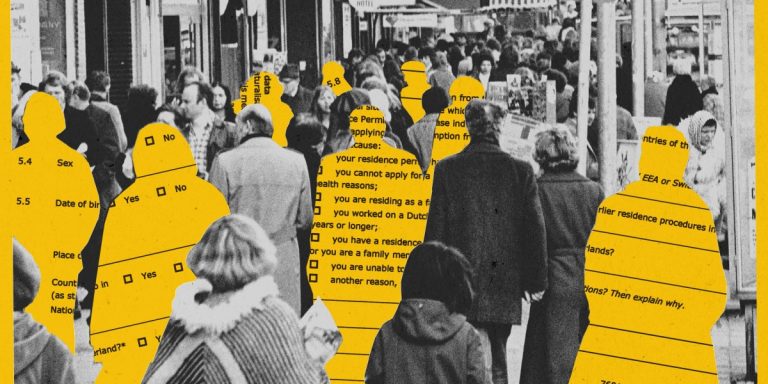

Officials have a large authority over the existing social protection candidates and beneficiaries. They can request bank files, convene beneficiaries at the Town Hall and, in some cases, make unexpected visits to a person’s home. As the surveys are carried out – or fixed paperwork errors – payments needing need can be delayed. And often – in more than half of the requests on requests, according to figures provided by Bodaar – the city finds no evidence of reprehensible acts. In these cases, this can mean that the city has “wrongly harass people,” says Bodaar.

The intelligent control system was designed to avoid these scenarios by finally replacing the initial social worker who reports which cases to send to the investigation service. The algorithm would close the applications to identify the most likely to involve major errors, depending on certain personal characteristics, and redirect these cases for a more in -depth examination by the application team.

If everything was going well, the city wrote in its internal documentation, the system would improve the performance of its human social workers, signaling less candidates for the investigation into well-being while identifying a biggest proportion of cases with errors. In a document, the city has planned that the model would prevent up to 125 individual Amsterdammers from facing debt collection and save 2.4 million euros per year.

Smart Check was an exciting prospect for city officials as of Koning, who would manage the project when it was deployed. He was optimistic because the city adopted a scientific approach, he said; It would “see if it would work” instead of taking the attitude that “it must work, and whatever happens, we will continue.”

This is the kind of daring idea that attracted optimistic technicians like Loek Berkers, a data scientist who worked on Smart Check in his second job at the University. Speaking in a cafe hidden behind the town hall of Amsterdam, Berkers remembers having been impressed during his first contact with the system: “especially for a project within the municipality”, he said, it was “a kind of innovative project that was trying something new”.

Smart Check used an algorithm called “Explainable Boosting Machine”, which allows people to understand more easily how AI models produce their predictions. Most other automatic learning models are often considered “black boxes” performing abstract mathematical processes that are difficult to understand for employees responsible for using them and people affected by results.

The intelligent control model envisaged 15 characteristics, especially if the candidates had previously requested advantages or advantages, the sum of their assets and the number of addresses they had in the file – to allocate a risk score to each person. He deliberately avoided demographic factors, such as sex, nationality or age, which would lead to biases. He also tried to avoid “proxy” factors – like postal codes – which may not seem sensitive to the surface but can become so if, for example, a postal code is statistically associated with a particular ethnic group.

In an unusual step, the city has disclosed this information and shared several versions of the intelligent control model with us, effectively inviting the external examination in the design and function of the system. With these data, we were able to build a hypothetical social protection recipient to have an overview of how an individual candidate would be assessed by Smart Check.

This model was formed on a set of data encompassing 3,400 previous surveys on social assistance beneficiaries. The idea was that it would use the results of these investigations, carried out by the city’s employees, to determine which factors in the initial applications were correlated with potential fraud.