Polson, Montana – When someone accused of a crime in this little northwest of the city of Montana needs mental health careThere is a good chance that they will be locked in a prison cell in the basement the size of a closet without an appointment.

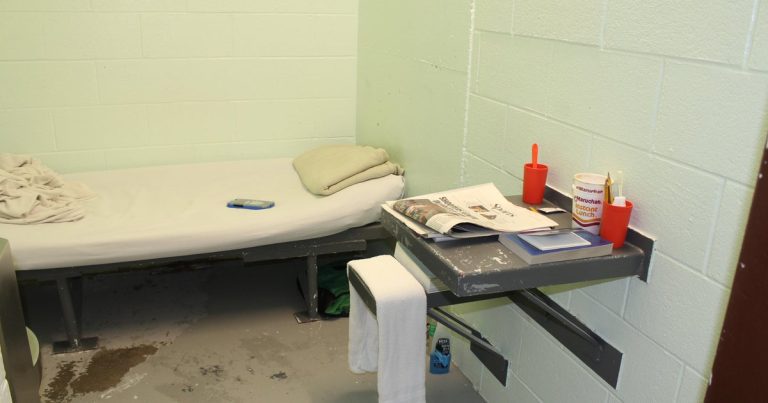

The prisoners, some detainees in this isolation cell for months, have scratched the initials and the expression “love hurts” in the brown paint of the metal door. Their rhythm carried a path in the cement floor. Many are detained in a kind of limbo, not found guilty of a crime but not stable enough to be released. They sleep on a narrow bed next to the toilet. The only view is a lane lit by fluorescent visible through a small window in the door.

Lake County’s lawyer James Lapotka was held at the center of the cell by speaking of people he helps to limit here. He stretches his arms, his fingers just shy to touch the opposite walls. “I receive anxiety right here,” said Lapotka.

Katheryn Houghton / Kff Health News

Last year, a man was sentenced to having stolen a rifle remained in this 129 -day cell. He was waiting for a place to open at the only psychiatric hospital managed by the state after an assessor of mental health held that he needed care, according to the judicial archives.

A man in the next cell almost at the same time was on the same waiting list about five months. He faced almost daily relays in the prison emergency chair – a steel machine wrapped in foam with straps for his shoulders, arms and legs. He regularly saw the prison mental health doctor. However, Joel Shearer, a detention commander of the county of Lake, said that the man had regularly experienced psychotic episodes and asked to be locked up on the chair when he felt that one besides staying there and remained there until his cries calm down.

“Someone who has a mental health crisis – they don’t belong here,” said Lapotka. “We have nowhere else.”

Katheryn Houghton / Kff Health News

The two isolation cells of around 30 square feet of the county of Lake are an example of the way in which communities at the national level are Do not provide mental health services – Crisis care, especially. Almost half of people Local prisons in the United States have mental illness.

More than half of the 23 wyoming sheriffs Said legislators there That they lived on people in crisis awaiting mental health care for months, Wyofile reported in January. Nevada faded despite A daily fine of $ 500 For each imprisoned patient whose treatment is delayed. Oregon disabled rights said Delays in this state continue after two people died in prison in the state’s psychiatric waiting list.

In Montana, the counties imprison mental health patients that they are not equipped to manage when the Montana state hospital is at full capacity. Few local hospitals have their own hospital psychiatric beds. Consequently, those arrested for anything, from the small flight to criminal assault can be imprisoned for months or more, because their mental health is getting worse. Many have not been found guilty of a crime.

Officials of Montana have known for years They have a problem. State officials said they had no space for all those ordered in the hospital. The psychiatric hospital has 270 beds, with 54 for people in the criminal justice system. Staff shortages can further reduce this capacity.

The Ministry of Public Health and Social Services of Montana two invoices This legislative session which Shouted The state of responsibility for delays when the Montana State Hospital is full. Before invoices, The agency wrote The hospital “had difficulty maintaining appropriate levels of care” due to money and endowment constraints, a lack of community services and not to control the flow patients that the Montana courts send.

The agency also announced on April 23 that $ 6.5 million was available Thanks to unique subsidies to help set up mental health stabilization services.

Officials said patients deserve care closer to their homes, in less restrictive contexts. But the counties say that the necessary local services do not exist.

“You must first do difficult things,” said Matt Kuntz, executive director of the Montana section of the National Alliance on mental illness. “You have to build the beds.”

Health defenders supported a proposal that require that the state pays for community commitments. This measure is headed for the Republican Governor Greg Gianforte after having passed the State House and Senate. Another bill that was still pending Create a new psychiatric hospital For people in the justice system. But the implementation of these ideas could take years.

The number of hospitalization beds for people with a serious national mental illness fell. At one point, this drop was intentional, part of a movement far from locking people in psychiatric hospitals managed by the state. But the planned correction, the local centers of the house, did not fill the void.

One of the largest suppliers in Montana, Western Montana Mental Health Center, had to close some of its crisis sites Due to money problemsWestern CEO said Bob Lopp. This includes an establishment within one mile from Lake County prison.

“If this is not where the funding is, you cannot do it for the concern of the argument and hope that it happens,” said LOPP.

Gianforte has promised to pay money into the reconstruction of the State’s behavioral system. Mental health agents of small towns find such promises of trust after seeing local services come and go for years.

The spokesman for the Health Department, Holly Matkin said that the agency was proud of his work to repair “the systems that have been broken for too long” and that he will improve services for people who need care for patients hospitalized in their communities.

The county of Lake is known to foreigners as a judgment worthy of Instagram on the way to the Glaciers National Park. He rides the Indian reservation with flat headsTerre du Bitterroot Salish, tribes of ear and kootenai. It houses a slice of rocky mountains and a bridge towards millions of acres of a wild nature. Polson, the county headquarters and the prison site, is a city of 5,600 on the southern shore of Lake Flathead, one of the largest lakes west of the Mississippi.

Vincent River has worked as the only mental health clinician in prison for 25 years. He said he was not always available because he is the only psychologist in four counties in the northwest of Montana evaluating if a person in prison needs psychiatric care.

Some are Careless outing If they linger too long on the waiting list of the state hospital.

“I speak to members of these family members. I hear them pleading with their fear in their voices and telling me everything that has been going on for days or weeks or months,” said River. “And then I can’t bring people into the hospital. It’s a giant crisis.”

It’s not just the state hospital. River said he couldn’t bring people into a psychiatric bed in Montana because there are too little. Instead, he tries to stabilize people while they are imprisoned. Which has deficits.

The prison cannot force a person in psychosis to take medication without a prescription from the court and a qualified doctor at hand to administer the prescription. The aging installation of the county of Lake has faced with prosecution Due to poor conditions in the middle of overcrowding, and the river must see the patients wherever there is room.

There is not even a space for the prison restraint chair. Prison employees leave prisoners finished in a corridor or changing rooms.

River said many are gradually improving and leaves isolation. Some do not.

“They languish there, psychotic and alone,” he said, “at the mercy of what the voices tell them.”

The inhabitants work to fill a few shortcomings. A mobile team launched in February has people who lived with mental disorders and drug addiction to provide support by peers. But someone really in crisis has only two options: prison or an emergency room.

The room reserved for people in crisis from the Providence St. Joseph Medical Center in Polson leaves the patients isolated and without privacy. The thick glass of the locked door looks on an animated emergency corridor.

Those who deteriorate enough to be deemed dangerous for themselves or to others are sent to prison.

Rebecca Bontadelli, an emergency doctor, said patients can be hosted in the room for days while hospital workers are traveling Montana and neighboring states for an open psychiatric bed. Some reject care in the meantime.

“We don’t really help them,” said Bontadelli. “They feel like they are in prison.”

Kff Health News is a national editorial room that produces in -depth journalism on health problems and is one of the main operating programs in Kff – The independent source of research on health policies, survey and journalism.