Fifty years after the fall of Phnom Penh in the rebellious army Khmer Rouge, The events of April 17, 1975 Continue to throw a shadow on Cambodia and its political system.

Emerging from the sampling of blood and chaos of the propagation war in neighboring Vietnam, the radical movement of Pol Pot has risen and defeated the regime supported by the United States of General Lon Nol.

The war culminated five decades ago on Thursday, the Pol Pot forces sweeping in the capital of Cambodia and commanding more than two million people in the city in the countryside with a little more than the personal effects they could transport.

With the abandoned Cambodia urban centers, the Khmer Rouge has embarked on the reconstruction of the country of “Year Zero”, transforming it into an agrarian and classless society.

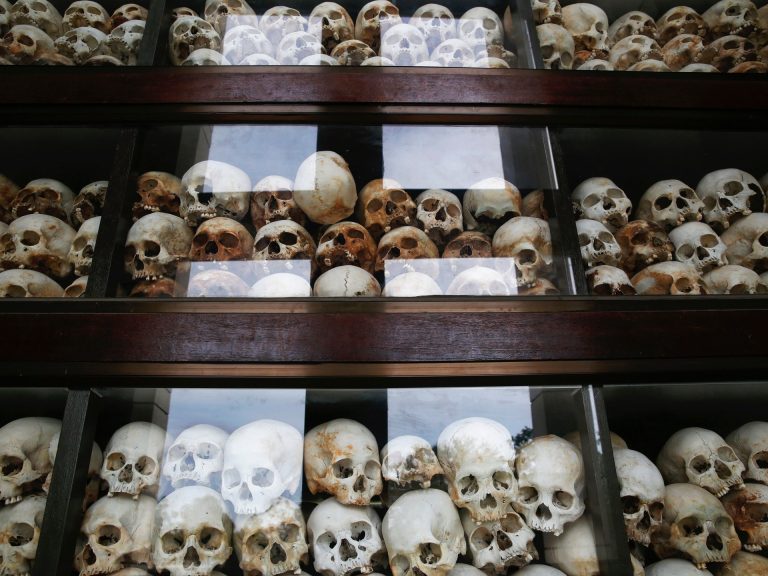

In less than four years under the reign of Pol Pot, between 1.5 and three million people had died. They would also eliminate almost the rich history and cultural religion of Cambodia.

Many Cambodians have been brutally killed in the “killing fields” of the Red Khmer, but much more died of hunger, illness and exhaustion in collective farms to build the rural utopia of the communist regime.

At the end of December 1978, Vietnam has invaded alongside Cambodian defectorsTurning the Red Khmer of Power on January 7, 1979. It was from this moment that popular knowledge of contemporary tragic history of Cambodia generally ends, taking up in the mid -2000s with the beginning of the former leaders of the United Nations regime.

For many Cambodians, however, rather than being relegated to history books, the fall of Phnom Penh in 1975 and the overthrow of the Red Khmer in 1979 remain alive, anchored in the Cambodian political system.

This tumultuous period of Khmer Rouge is still used to justify the long -standing rule of the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) in variable forms since 1979, and the personal rule of RPC Hun Sen and his family since 1985, according to analysts. It was the aging senior management of the CPP which joined the Vietnamese forces to oust Pol Pot in 1979.

While the memories of these times fade, the The grip of the CPP on power has been as firm as ever in decades since the late 1970s.

“The manufacture of a political system”

The CPP in power considers itself “as the Savior and the Country Guardian,” said Aun Chhengpor, a policy researcher in the future forum reflection group in Phnom Penh.

“This explains the manufacture of a political system as it is today,” he said, noting that the CPP has long done what to make sure they are still there at the helm … at all costs “.

Most Cambodians have now accepted a system where peace and stability are above all.

“There seems to be a non -written social contract between the establishment in power and the population which, as long as the PRC provides relative peace and a stable economy, the population leaves governance and politics to the RCP,” said Aun Chhengpor.

“The situation as a whole is how the CPP perceives and its historical role in modern Cambodia. It is not so different from the way in which the establishment of the Military Palace in Thailand or in the Communist Party in Vietnam see their roles in their respective countries,” he said.

The CPP led a regime supported by the Vietnamese for a decade, from 1979 to 1989, bringing an order relating to Cambodia after the Red Khmer, even if the fighting persisted in many regions of the country while the fighters of Pol Pot were trying to reaffirm control.

With the support which decreases by the Soviet Union in the last days of the Cold War and an economically and militarily exhausted Vietnam of Cambodia, Hun Sen, then the head of the country, agreed to hold elections within the framework of a regulation to end the civil war of his country. From 1991 to 1993, Cambodia was administered by the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC).

The Cambodian monarchy was officially restored and the elections took place for the first time in decades in 1993. The last Khmers Red soldiers went in 1999, symbolically closing a chapter on one of the bloodiest conflicts of the 20th century.

Despite a ribbing road, there were initial hopes for Cambodian democracy.

The royalist National Front for an independent, neutral, peaceful and cooperative Cambodia party – better known under its acronym Funcinpec – won the elections not administered in 1993. Faced with defeat, the CPP refused to yield power.

The late Norodom Sihanouk king intervened to negotiate an agreement between the two sides which preserved the peace harshly won and made the election a relative success. The international community has signed up for relief, because the USAC mission in Cambodia was the largest and most costly at the time for the world organization, and the UN member states were desperate to declare their investment in the nation rebuilding success.

Regulating jointly under a power sharing agreement with the CPP and the Co-Prime Ministers of Funcinpec, the unstable alliance of the former enemies detained for four years until a quick and bloody coup of Hun Sen in 1997.

Mu SOCHUA, an exiled opposition leader who now directs the Khmer Non -profit Khmer movement for democracy, told Al Jazeera that the resistance of the RPC to a democratic transfer of power in 1993 continues to repercussions throughout Cambodia today.

“The failure of the transfer of power in 1993 and the agreement that the king concluded at the time … was a bad deal. And the UN continued because the UN wanted to close the store,” she told Al Jazeera in the United States, where she lives in exile after being forced to flee the intensifying authoritarianism of the RPC at home.

“The transition period, the transfer of power … which was the will of the people, never happened,” said Mu Sochua.

End of the war does not mean the beginning of peace

After the coup in 1997, the CPP was not close to losing power before 2013, when they were challenged by Cambodia National Party (CNRP), largely popular.

At the time of the next general elections in 2018, the CNRP was prohibited from policy by the courts less than independent of the country, and many opposition leaders were forced to flee the country or found themselves in the politically reasoned prison.

Without hindrance by a viable political challenger, the HUN Sen RPC won all seats in the national elections of 2018, and all 125 parliamentary seats except five disputed in the last general elections in 2023.

The CPP has also firmly aligned with China, and the country’s free press of the country has been closed and civil society organizations have been intimidated in silence.

After having marked 38 years of power, Hun Sen dismissed as Prime Minister in 2023 to make way for his son Hun Manet – a sign that the political machine led by the CPP has eyes on the dynastic and multigenerational rule.

But new challenges have emerged in the decades of relative prosperity of Cambodia, the enormous inequalities and the unique de facto rule.

The Cambodian in full swing microcredit industry was intended to help withdraw Cambodians from poverty, but the industry has rather overwhelmed families with high levels of personal debt. An estimate put the figure at more than $ 16 billion in a country with a population of only 17.4 million inhabitants and a gross domestic product (GDP) of $ 42 billion in 2023, according to the estimates of the World Bank.

Aun Chhengpor told Al Jazeera that there were signs that the government takes note of these emerging problems and these demographic changes.

Hun Manet’s cabinet moves towards “performance -based legitimacy” because they do not have the “political capital” formerly granted by the public to those who released the country of Red Khmer.

“The proportion of the population who remembers the Khmer Rouge, or who has memories that can be used from this period, shrinks from year to year,” said Sebastian Strangio, author of the Cambodia of Hun Sen.

“I do not think that (the inheritance of the CPP) is sufficient for the majority of the population born since the end of the Cold War,” Strangio told Al Jazeera.

Now, there seems to be room for a limited quantity of popular opposition, said analyst Aun Chhengpor.

In January, Cambodian farmers blocked a main highway to protest against the low prices of their goods, which suggests that there could be “a certain space” in the political system of dissent located on community issues, he said.

“(It will be) a difficult struggle for the fracturing of the political opposition to prosper – not to mention the organization between them and, not to mention, to have the hope of winning a general election,” said Aun Chhengpor.

“However, there are indications that the CPP still believes in a way in the multi-party system and limited democracy of the way in which they can have their say at the moment and the quantity of democracy,” he added.

Speaking in exile from the United States, Mu Sochua had a view of gradation of the situation of Cambodia.

In the same month as farmers’ protests in Cambodia, a former Cambodian deputy for the opposition of the Parliament was shot in broad daylight in a street in the Thai capital, Bangkok.

The cheeky assassination of Lim Kimya, 74, a double Cambodian citizen, recalled memories of chaotic political violence in the 1990s and the early 2000s in Cambodia.

Peace and stability, Mu Sochua said, only exists on the surface in Cambodia, where the waters are still deep.

“If politics and space so that people get involved in politics are nonexistent, which dominates is not peace,” she said.

“It is always the feeling of war, insecurity, lack of freedom,” she told Al Jazeera.

“After the war, 50 years later, at least there is no bloodshed, but that alone does not mean that there is peace.”