Speaking on Sunday of BBC One with Laura Kuensberg, Wes Street, British Secretary of Health, expressed his concerns that certain mental health conditions have been overshadowed. The conversation asked two experts to comment on the sttingy complaint. Is the secretary to health right?

Mental distress is underdiagnosed – but too medicalized

Susan McPherson, professor of psychology and sociology, University of Essex

A year ago, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the curator Rishi Sunak, announced “Culture of sick notes” had gone too far. His secretary of work and pensions said “Mental health culture”Mel Stride, had gone too far.

These statements have merged concern about the affiliation of disability services with ideas on the overdiagnosis of mental illness. It seemed to be in response to a Foundation resolution reportA thinkank.

The report indicates that people in their twenties were more likely to be unemployed than people in their forties. The report assigned this to an increase in young people reporting mental distress (from 24% in 2000 to 34% in 2024).

This was used by some journalists to support the idea of Young people like maximum snowflakes pretending to be mental illness, which has angry a lot handicap activists, mental health activists and members of the opposition labor party.

A year later, the United Kingdom now has a Labor government. Wes Streting, the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, is confronted with criticisms for having echoed conservative tropes. In an interview concerning government plans to reduce the advantages for disabled people, he agreed that overdiagnosis explains an increase in people in terms of services due to mental illness. This seems to reflect these media stereotypes on maximum work millennials.

If that’s what the streets meant, then the evidence is not on its side. Ten years ago, A British national survey on psychiatric symptoms found that a third of people whose psychological symptoms were serious enough to deserve a diagnosis did not have a diagnosis.

More recent research using Study of longitudinal households in the United Kingdom Grouping in grouping depending on whether or not they make a psychiatric diagnosis and whether or not they have sufficiently serious psychological symptoms to deserve a diagnosis. The study found 12 times more people in the “not diagnosed distress” category (with serious symptoms but no diagnosis) than the over-diagnosed category.

The study also identified significant inequalities. People living with a handicap had almost three times the risk of unmatched distress compared to people without disability.

Women had 1.5 times the risk of not diagnosed with men. Lesbians, homosexuals or bisexuals were 1.4 times more likely to have unmatched distress compared to heterosexual people. People aged 16 to 24 had the highest risk compared to all other age groups.

All of this suggests that inequalities in unmatched distress are a much more important problem than overdiagnosis in the United Kingdom. Since many forms of support in the United Kingdom depend on a diagnosis, an unmatched distress probably means that people do not get the support they need.

However, Streetting also said That too many people “simply do not get the support they need. So if you can get this support for people much earlier, you can help people stay at work or go back to work. ”

Given this nod to the prevention and the importance of non-medical support, it is conceivable that the feeling of street was on the “over-medication” of mental distress rather than on the diagnosis of over-diagnosis. The difference is important.

The term “diagnosis” reflects a medical model of mental illness. Many should be that the medical idea of ”diagnosing and treating” does not serve people with mental distress. This is because there is a a lot of evidence suggesting that the underlying causes of mental distress are social, economic, environmental or the result of past trauma.

If the Street had said “over-medicated”, it would have been in line with an increasing global concern concerning the over-medication and the overexraire of drugs to treat mental distress, a position recommended by the UN And The World Health Organization.

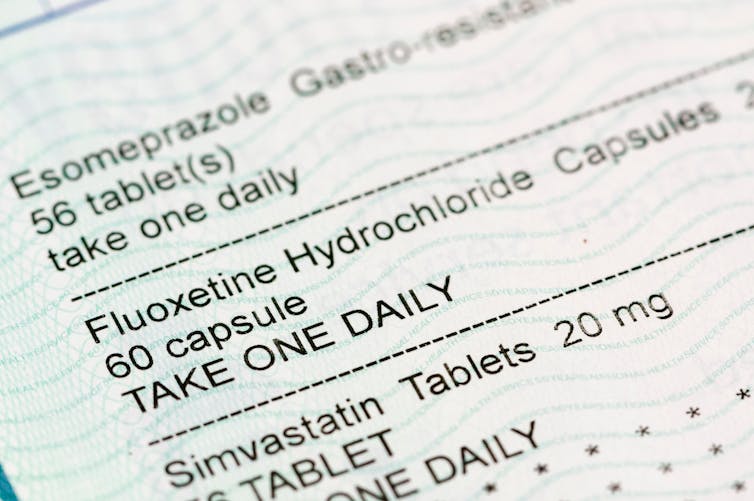

Despite the British directives recommending psychological treatments as front line interventions for depression, the prescription of antidepressants has increased by 46% in the past seven years with more than 85 million Prescriptions in 2022-233. This alongside a Increase in long -term use of psychiatric drugs without reduction of mental distress at the level of the population. If the street had said “too medical”, the evidence would have been.

Stephen Barnes / Medical / Alamy Photo

Mental health diagnosis is only a label – and generally useless

Joanna Moncrieff, professor of critical and social psychiatry, UCL

There has been a spectacular escalation in the number of people looking for treatment for mental health problems in recent years. In April 2023 to 2024, 3.8 million people were in contact with mental health services in England only, which is 40% higher than before the cocovable pandemic. The figures include 1 million children. One out of five 16 -year -old girl is in contact with services.

Statistics reveal a tendency to overcome a variety of human problems that has been supercharged by the pandemic and which will likely lead to harmful and mental health effects.

What many people do not do about a mental health diagnosis is that it is in no way similar to the diagnosis of a physical condition. It does not name an underlying biological state or process which may explain the symptoms that a person feels, as is the case when someone obtains a diagnosis of cancer or rheumatoid arthritis, for example.

A mental health diagnosis does not explain anything. It is simply a label that can be applied to a certain set of problems. The process by which this label is conferred is neither scientist nor objective and is influenced by Commercial, professional and political interests.

In most situations, giving people with mental health problems a diagnostic label is useless. He convinces people they have a biological defect, this leads to ineffective and often harmful medical treatment, and most of the time, real problems are missing.

Because obtaining a diagnosis implies that you have a medical condition, it misleads people thinking that they have an underlying biological anomaly, like a chemical imbalance, even if there is no good proof that mental disorders are caused by underlying or corporal cerebral dysfunctions. Research has shown that it makes people pessimistic about their chances of recovery and Less likely to improve.

The diagnosis diagnosis often leads to prescribing a psychiatric drug, such as an antidepressant. About 8.7 million people in England Now take an antidepressanthalf of them on a long -term base.

Prescriptions for other drugs, such as stimulants (prescribed for diagnosis of ADHD), are also get upeven by leading to drug shortages. However, proof that one of these drugs improves people’s well-being or the ability to operate is minimal. In addition, like all substances that modify our normal biological composition, in particular those that interfere with brain function, they cause side effects and health risks.

Antidepressants can cause serious and prolonged withdrawal symptoms, sexual dysfunction (which may persist) and emotional numbness or apathy, among others undesirable. Stimulants can cause Cardiovascular problems and neurological conditions. The widespread and unjustified prescription of these drugs will negatively affect the health of the population.

Giving people a diagnosis can also obscure the nature of the person’s underlying problems and prevent them from being treated.

Mental health problems are often significant reactions to stressful circumstances, such as financial problems, housing and the relationship and experiences of abuse, trauma, loneliness and lack of meaning. Reducing over-medication does not necessarily mean fewer services. What we need are different services that provide appropriate support for the real problems of people, not on the treatment of medical labels.

We also need ways to excuse people if necessary, without giving them the impression of having to assume a “sick” role which implies that they are forever sick and helpless.

A large part of today’s employment is Poorly paid, unsure, boring, exploiting and pressurizing. He shouldn’t surprise us that some people have trouble lasting. We must improve working conditions for everyone, but we must also support people who find these conditions particularly difficult, without having to qualify them as sick.