As technology progressed, humans also improved to transmit skills to other

English heritage images / Getty images

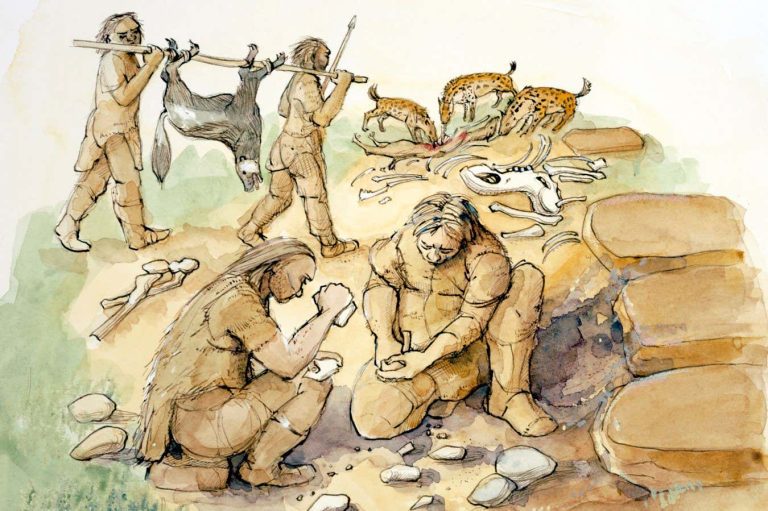

An analysis of more than 3 million years of human evolution shows that communication and technology have developed in Lockstep. While the former humans have proposed more advanced stone tools and other technologies, they also improved their skills in communication and teaching, in order to transmit their new capacities to the next generation – and this has made it possible to progress more technological.

“We have a scenario for the evolution of the mode of cultural transmission in human evolution,” says Francesco d’Errico at the University of Bordeaux in France. “It seems that it is a co-evolution between the complexity of the cultural line and the complexity of the cultural transmission mode.”

A distinctive characteristic of humans is that we have developed increasingly complex tools and behaviors. For example, ancient humans have created sharp stones that could be used for stabs and cutting, then attached them to wooden sticks to create lances – A technique known as HAFTING.

Above all, we can tell other people how to perform these behaviors. In the most complex cases, such as playing the violin or programming a computer, this can involve years of teaching and practice. But in a distant past, we were not as good for transmitting information – especially before the complex language arises.

With Ivan Colagè At the Pontifical University of the Sainte-Croix in Rome, Italy, Errico decided to follow how our ability to transmit cultural information developed during the 3.3 million years, as well as our changing behaviors and technologies. They followed 103 cultural features, including specific types of stone tools, ornaments such as pearls, pigments and mortuary practices such as burials and construction of cairns. They identified when each trait appeared regularly in the archaeological file, which suggests that it was a common practice.

The pair also evaluated how difficult each line was to learn. Some, like stone hammers, are quite simple. “You don’t need so many explanations,” says Rérico. However, the manufacture of more complex tools could be demonstrated, and the most complex behaviors – in particular things such as burial which have a deep religious meaning – require explicit verbal explanations.

To break this, of rekico and colagè have looked Three aspects of learning. First of all, spatial: Can you learn skill by looking at a distance, or do you need to be close enough to touch? Second, temporal: is a short lesson sufficient, or do you need several sessions, perhaps by focusing on different stages? And thirdly, social: Who learns from who?

The pair evaluated all the features themselves and also requested a panel of 24 experts for their assessments. They have largely accepted. “We believe that the answers are relatively robust,” explains Rérico.

The new works suggest that there have been two major changes in cultural transmission. First, about 600,000 years ago, ancient humans openly taught each other, but not necessarily using spoken instructions: gestures may have been sufficient. It is well before the origin of our species, Homo sapiensand coincides with the emergence of Hafting.

Then, between 200,000 and 100,000 years, humans developed modern language. This was necessary because they made behavior like burials. “This implies many different steps, and you must also explain why you are doing this,” said Rérico.

“The link between cultural transmission and cultural complexity is robust”, says Ceri Shipton at College University in London. He adds that, although there is a lot of uncertainty on the moment when humans have developed a language, the new estimate is “a reasonable time”.

Subjects: