On a sunny Wednesday morning in the Education municipalitiesThe undergraduate students gathered in groups with two long tables around a rigid loom, a portable table for loom and a small loop weaving kit. A 3D printer and manufacturing, circuits, coils, pearls and the resulting brushes border the walls and cubbies of the creation space, located in the George A. Weiss pavilion in Franklin Field.

Elly R. Truittassociate teacher in the Department of History and Sociology of Sciences in the School of Arts and Sciencesapproached a group of students weaving the lilac and the red thread in blue thread to ask what they represented with colors and patterns. Jajwalya “jaj” karajgikarThe librarian of applied data science, noted that last year, Penn libraries“The Literacy Interest Group has made a weaving in the loom representing what they felt of artificial intelligence.

The field excursion in common education was for the newly redesigned technology and society course of Truitt, which follows the discussions of communication technologies and information from the invention of writing to models of modern language (LLM) like Chatgpt.

What do professions have to do with communication and information technologies? Truitt explained that the punch card technology used in weaving was vital for the development of early machines and computers. In a previous class at Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts on the sixth floor of Van Pelt-Dietrich Library CenterStudents saw a rare book of hours at the beginning of the 19th century which was forged silk on a jacquard loom using punch cards.

“My definition of technology before my arrival in class was just digital. I did not know that physical things can be considered a technology, ”explains Heer Patel, a major biology of the third year of Philadelphia.

Justin Weisser, a student from the fourth year school of Wharton de Roslyn, New York, says that he loved the practical applications of the class – which physically interacts with the story has made it more called to it. “It is very easy to hold for the things we have in everyday life, and what I will take away from this course is that there is a vast story – of Millennières – for the world in which we live today,” says Weisse.

He and Heer appreciated that the course brought them to places on the campus that they did not know before and exposed them to different resources. “I would have liked to take it earlier,” says Weisse.

Mission accomplished for Truitt.

“The program is designed – and the assignments are designed – to give students this broader context to reflect on these urgent problems with which they face them, to present them the richness of university resources and to accustom students to use these resources,” explains Truitt. Tex Kang, coordinator of the technology and game program, encouraged students to return to common education goods, where they have up to 50 hours of free 3D printing per semester for personal use.

Contextualizing communication

Technology and company are a long -standing class – the one that is both a fundamental course for the Major of Science, Technology and Society and an optimistic course for the Health and companies (HSOC) major. By teaching the course for the first time this semester, Truitt – a Medievalist by training With research interests in automation and artificial intelligence, he was opposed to focus on communication technologies.

Students are already “sensitive to reflection on communication technologies. They are in our face every day, ”says Truitt, imitating the act of putting a phone a few centimeters from his face.

She says that she wanted students critically reflecting the contemporary problems of technology but in a broader context, with another educational objective of ensuring that “students really reflect on how technology has been naturalized in their lives” – and no technology more than writing. She also wants to bring students to think how They learn.

“The idea is that by learning this longer story and with experiential commitment with the material, they will have a good idea of what we do in the humanities and how to learn in different ways,” explains Truitt. “And they will also have intellectual tools to understand what type of LLM tools as cat -gpt, and in which they are good and what are the costs and benefits of using them – personally and social.”

In a class, the students used Play-Doh to understand how to represent the goods they needed and exchange them without speaking. They also had a guest conference from Timothy HogueA teacher in the Department of Middle East languages and culturesWho teaches the visible writing of the course: the history of writing systems.

The major in fourth year chemistry, Sarah O’konski, says: “It’s so easy – especially in science – to have a narrow perspective”, but this course has widened its horizons. So far, she had spent a lot of time learning science without teaching her history. This semester, however, took technology and society and medicine in history and was interested in scientific communication. In Truitt’s course, she says she found fascinating how science documentation has changed over time.

“I think we update previous cultures as less advanced, but we have seen through this class that there has been so much progress,” explains O’konski, who comes from Sugar Notch, Pennsylvania. She “also really liked to obtain this wider perspective which is not entirely Eurocentric”.

Explore Penn’s resources

“Penn’s story is really important in terms of computer history,” said Truitt. For example, Eniac – the first digital computer for general use of the world – was Built and operated in Penn During the Second World War.

Then there are the many acquisitions that help researchers understand the evolution of communication technologies. The class visited the Penn Museum To see the first Mesopotamian tokens and the cuneiform tablets which follow the invention of writing. They also watched quippedIncan textiles used to transmit information through a series of nodes and colors.

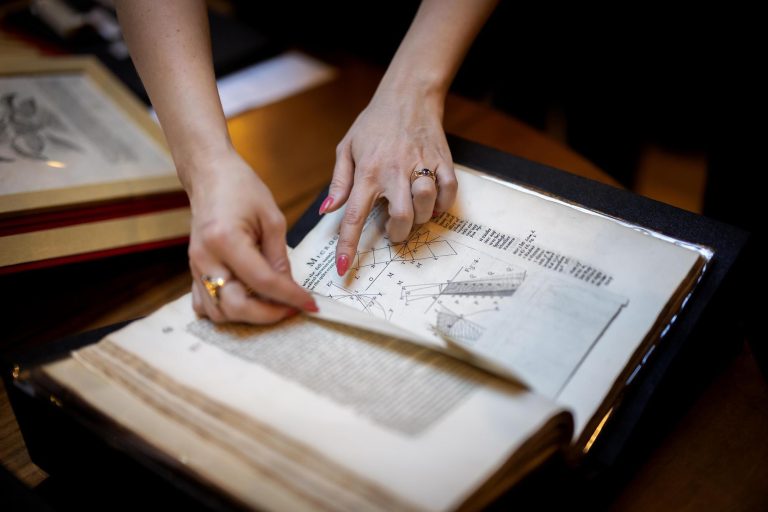

In the Kislak Center for another class period, the students examined (with freshly washed hands) materials that Alicia MeyerKislak Center research curator, arranged around the table and explained.

There was the Egyptian clay tablet of 400 BCE, which a banking family held as a debt record. There was a huge roller of 19th century horoscope for a family in current India. There was an astronomical commoner, a tool to predict the movement of celestial bodies. There was an economic document on the papyrus, a Japanese wooden printing and central America posters made on sugar cane paper.

Truitt had asked for some specific elements for this visit, showing how Penn’s collections illustrate the variety of communication technologies over the centuries and how writing has evolved, but Meyer also presented the materials that Truitt had not known before.

Some materials illustrate how people can control access to information and how our information relationship changes over time. For example, Truitt joked on a book of figures from the 17th century in Spain: “If you are the Spanish Empire and you” empire “more than half of the world, you must be able to keep your information secret.” She also showed that a large part of what the philosopher William of Conche wrote in a 12th century text – on the cosmos, the earth and the elements – was blackened later, including a part on the female reproductive system and how babies are manufactured.

“We have a lot of unique and unique materials here,” Meyer told the class, including articles that “really can’t be replaced”. But, she added, everyone can teach us a lot about their moment in time and the culture that surrounds them. “Working with rare materials and with special collections, materials gives us access to countless aspects of history and stories that we will not have otherwise,” she said.