Editor’s note: This article is the third in a three-part series on enterprise systems modernization, DLA’s journey to replace its signature management technology.

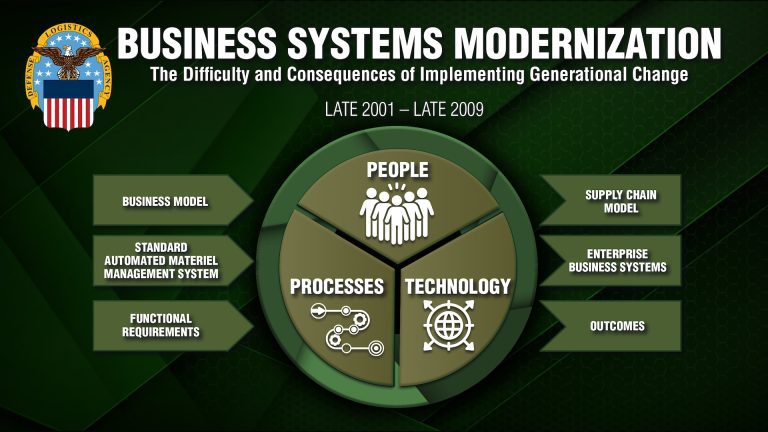

After years of losing ground to commercial offers, the Defense Logistics Agency finally began implementing operational systems modernization in November 2001. Previous efforts to replace the standard automated materiel management system had failed enough times to convince agency leaders that the only way to introduce new technology was to institute fundamental change. Not only would the agency replace SAMMS, it would also reconfigure offices, rewrite job descriptions and rethink operations.

Most structural changes have occurred in supply centers. Procurement orders in Philadelphia, Columbus, and Richmond had recently shifted from a commercial approach to a weapons systems approach. BSM solidified this transition while dividing the workforce between those who interacted with customers and those who interacted with suppliers. As part of this reorientation, the supply centers grouped 1,100 job descriptions into 179, affecting 5,000 people. As BSM expanded to other supply chains, those 5,000 employees became 8,000.

BSM also introduced new positions at DLA headquarters. At the recommendation of the Business Systems Modernization Steering Group, Navy Vice Adm. Keith W. Lippert, the agency’s 14th director, appointed national account managers – now service integrators senior – to conduct high-level planning with the military services. Similarly, DLA Logistics Operations has organized its business modernization leadership into planning, order fulfillment, procurement, financial management and quality assurance divisions.

A new philosophy underlies these changes. Simply put, the agency stopped following process-oriented models and started following results-oriented models. More precisely, we moved from supply management to supplier management, from mobilization via stocks to mobilization via industry, and from instant purchases to purchases on long-term contracts.

Changes in work and philosophy were prerequisites for technological change. While DLA focused on restructuring supply centers, its systems integrator, Andersen Consulting, led teams through a product development process called waterfall. Although comprehensive, waterfall development allowed technology providers Systems Applications and Products and Manugistics to modify commercially available products instead of designing new ones. Although DLA had a unique mission, the planning, order fulfillment, procurement, and financial functions it wanted to automate were common.

Events beyond DLA’s control continued to interrupt progress after the agency began replacing SAMMS. This time the problem was the collapse of Enron, which forced Andersen Consulting’s parent company, Arthur Andersen, out of business. While Andersen Consulting remained an independent company named Accenture, a gap developed in its support for the agency. DLA relied on the Defense Information Systems Agency to meet the schedule.

Advised by DISA, the agency transferred the items in stages. The initial phase, or “Go-Live,” began in July 2002 and covered 170,000 items, or 5% of the DLA inventory. The second stage began in November 2003 and focused on combat uniforms and livelihoods. Together, the two steps allowed DLA to acquire 1.9 million items with modern technology. To support this change, 550 employees at the Defense Supply Center in Philadelphia have opted for BSM jobs. The third and final stage began with the feature release in August 2004. It covered an additional 1.9 million items. Although deployments continued until December 2006 and the agency did not reach full operational capacity for another seven months, 2005 was the year of transition: the first year in three decades in which A material supply center purchased items without SAMMS.

After BSM proved effective, the agency received authorization from the Office of the Secretary of Defense to expand the program. In an effort called Enterprise Business Systems, DLA has developed enterprise resource planning systems for accounting, real estate, electronic purchasing, energy, inventory positioning and purchasing for the industry audience. While this arrangement reflects how the agency has expanded SAMMS, the system applications and products ensure that all EBS programs communicate seamlessly with each other, something the agency’s initial management system struggled to do.

EBS has been DLA’s management technology longer than most of the agency’s employees. Today, the DLA finds itself where it was in the 1990s, with current systems second-tier but functioning well enough to mask the need for a transition. The situation is, however, different in at least one aspect. While DLA leaders were reluctant to replace SAMMS, their successors decided to retire EBS before it became imperative. If this eagerness can be attributed to foresight, DLA leaders also demonstrated foresight in the 1990s. What makes 2024 different is the ease with technological change and the limited disruption expected from that change. Immersed in electronics, today’s managers are more willing to replace systems than ever before. Because the systems they put in place require professional retraining, and not reductions or reclassifications, employees accept their necessity more easily.