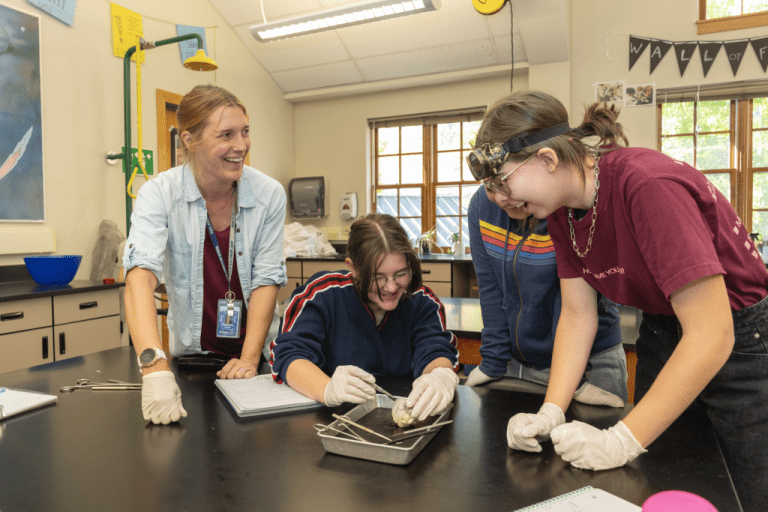

Vail Mountain School/Courtesy photo

One of Vail Mountain School’s high school science classes has a different origin story than the others. Neuropsychology, proposed five years ago by a student looking for an alternative to traditional scientific offerings, is a fan-favorite discipline every year.

The class is the brainchild of Will McLoota, who graduated from Vail Mountain School in 2022. During his junior year, as he began to look at courses offered for his senior year of high school, McLoota was less attracted to the offers science, but knew he was interested in studying the brain.

“I feel like it filled a gap that didn’t exist in a lot of places.” It’s another opportunity to learn something that might be different but still interesting,” McLoota said. “It’s not a typical biology, chemistry or ecology class, but it’s actually another opportunity for people who want to learn something different.”

He approached the leadership of the science department, and the staff gave him a series of tasks he would need to undertake to create a class, including finding other interested students and researching similar courses at other schools.

“I think they didn’t really expect me to do that,” McLoota said.

Support local journalism

But he researched further and returned to the school administration with the required evidence, including finding a comparable class at another school.

“Will did his homework,” said Ross Sappenfield, chair of the science department at Vail Mountain School.

The science department took up McLoota’s research and continued it over the next few months, with anatomy and physiology professor Steph Lewis jumping at the chance to teach the class.

“The brain is extremely complicated and there is so much we don’t know,” Lewis said. “I try to make science fun and interesting for everyone, even for kids who aren’t usually interested in it, and I try to make it applicable to their daily lives. It’s always a question of balance for me: figuring out how to take the very complex parts of neuroscience, make them accessible and fun.

The following fall, McLoota was able to take the class he had dreamed of.

Be better informed in 2025.

Sign up for daily or weekly newsletters at VgarlicDaily.com/newsletter

“It was really cool,” McLoota said. “It’s different when someone teaches you something rather than trying to do the research yourself. I feel like you can take a different approach, especially when you’re learning in a group rather than just out of curiosity. It’s nice to have that extra level of learning opportunities.

Although he enjoyed taking the course himself, the most rewarding part, McLoota said, was seeing his classmates immerse themselves in science.

“I was really excited to see other people enjoying this class. I think that was the best part,” McLoota said. “Seeing a classroom full of people equally interested at the same time was really cool for me. »

The course is now in its fourth year, with full enrollment each year. “Every year, students say this is by far one of their favorite classes they have taken at Vail Mountain School,” said Upper School Principal Maggie Pavelik.

“I think it speaks volumes about what started with one student’s curiosity and became incredibly impactful at our graduate school,” Pavelik said.

“I think part of this is due to a dynamic curriculum that is constantly evolving and the fact that we are constantly looking to improve what we teach and how we teach it,” Pavelik said. “This is partly due to their peers who are also curious and really engaged in the course. And part of that is due to a truly dedicated teacher. Steph Lewis has devoted a lot of time and energy to the creation and continued development of this class.

More than just a science lesson

The course is more than a science course. It’s a way for students to learn how to become more functional, more effective, and even better people.

“I think there are many ways to learn more that can help them outside of the classroom, not just in science class,” she said. “It’s science, but it’s also life.”

“One of the biggest issues among American teenagers is mental health,” Sappenfield said. “That students have the opportunity to understand how the brain works while they are still in high school seemed extremely relevant to me. »

The year-long science elective, open to juniors and seniors, includes several units, including memory and sleep, sensation and perception, developmental process, and neurodiversity.

“This is truly a cell biology based course that looks at the nervous system at the cellular level and then relates it to behaviors, development and psychology in a way that teens can really relate to” , Sappenfield said.

All science courses at Vail Mountain School are required to include a laboratory component, and neuropsychology labs see students studying other students, sheep brains and themselves.

“Our brains are always available for us to do experiments,” Lewis said.

In the memory unit, students test different ways of remembering things, comparing themselves to those who can remember certain things better over time.

“We do a lot of self-testing or do a lot of experiments on ourselves to illustrate different phenomena,” Lewis said.

During the developmental unit, students design and perform experiments on other Vail Mountain School students of different ages to learn about the different ways the human brain changes as people age.

In the sleep unit, students track their sleep, analyzing variables such as how much sleep they get each night, how much and when they exercise, and other interacting factors. After the unit, students set and track their progress toward goals based on what they have learned.

“It fits very well with being an 11th or 12th grader in high school, where we really have to take care of ourselves and our sleep,” Pavelik said.

The same goes for other units in the classroom: students can apply what they learn in class to their interactions and decisions in the outside world.

“Juniors and seniors…maybe they see people using drugs and alcohol, and they can see the effects of that. And then knowing the science behind it is extremely helpful,” Lewis said.

“If you better understand how the brain works, you have the opportunity to develop more empathy for differences in how the brain works,” Sappenfield said. “And I think we have an incredible empathetic community here that may or may not be the result of students learning more about brain functions.”