CNN

—

“Ooh, that’s a big deal.” Donald Trump said Monday as he signed an executive order – one of dozens in his first hours as president – to withdraw the United States to the World Health Organization.

What is behind this decision and what could be the impact? The WHO, the United Nations health agency that helps protect the health and safety of the world’s populations, receives about one-fifth of its budget from the United States.

Trump has called the WHO “corrupt” and accused it of ripping off America, and the millions of Americans who voted for him are increasingly skeptical of the value of such international structures. But experts have warned that removing the WHO’s most influential member could harm global health.

In a statement Tuesday, the organization said it regretted the U.S. decision, noting that it had “implemented the largest set of reforms in its history over the past seven years, to transform our accountability, profitability and impact.” in the countries”.

The U.S. withdrawal is the “most significant” of all the executive orders signed Monday, said Lawrence Gostin, a professor of public health law at Georgetown University, warning that it “could sow the seeds of the next pandemic.”

Here’s how Trump’s decision could affect the WHO and global health more broadly.

The WHO is one of many global institutions born from the rubble of World War II. After the world was torn apart by nationalism and conflict, countries agreed to sacrifice aspects of their sovereignty for the common good.

The agency was founded in 1948 with the aim of protecting global health. Its constitution, signed at the time by all members of the UN, warned that the “uneven development” of health systems in different countries constituted a “common danger”. The goal of the organization is “the attainment by all people of the highest possible level of health”.

Thomas Parran, then the U.S. surgeon general, said the WHO was more than a health agency, but a “powerful instrument forged for peace” that would “contribute to the harmony of human relations.”

Today, the agency works in more than 150 locations around the world, leading efforts to expand universal health coverage and leading the international response to health emergencies, from yellow fever to cholera and Ebola.

The agency, however, has been criticized for being inefficient, opaque, overly dependent on private donors and paralyzed by political concerns.

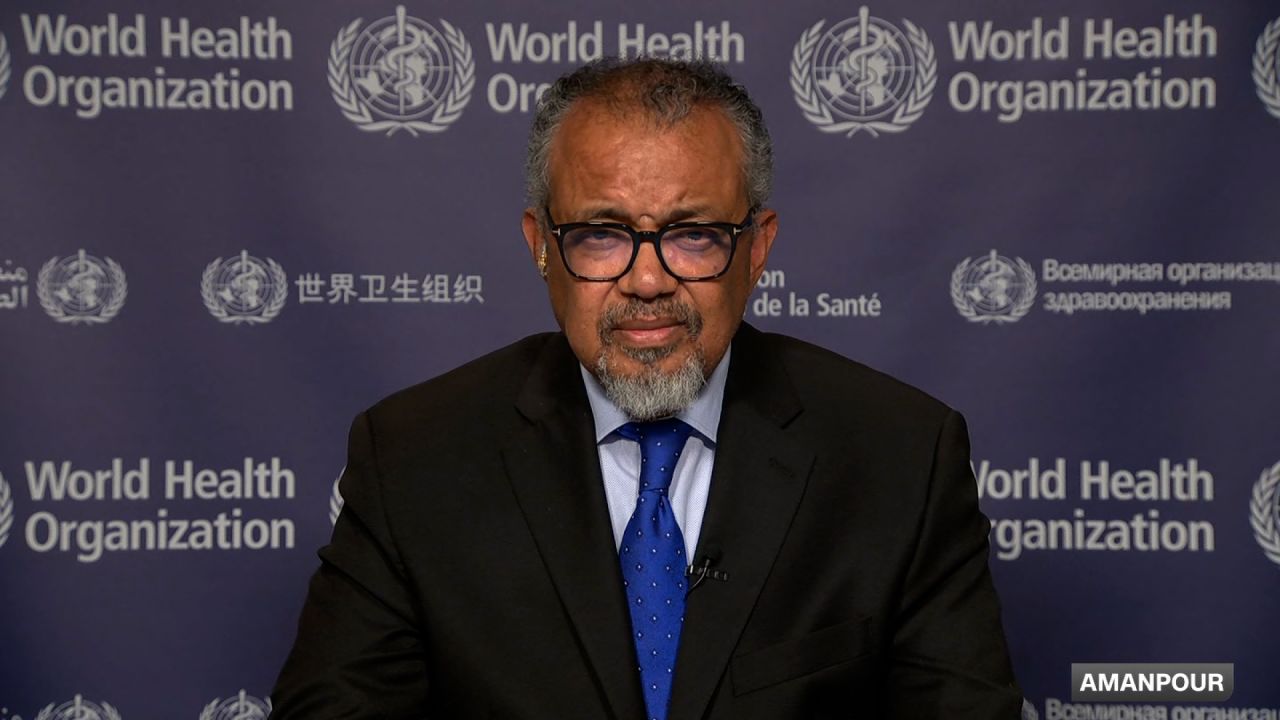

Falling global vaccination rate ‘very concerning,’ says WHO chief

The WHO’s most notable achievement was the eradication of smallpox, a rare example of cooperation between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

In 1967, the organization set the ambitious goal of eradicating the disease within a decade. The last known case occurred in Somalia in 1977. By 1980, the WHO was able to declare smallpox eradicated – the only infectious disease to achieve this distinction.

Due to the size of the organization, its effects are often “diffuse”, said François Balloux, director of the Institute of Genetics at University College London (UCL). He highlighted the near-universal upward trend in life expectancy since the WHO’s inception as an achievement for which the agency also deserves credit.

More recently, it has led responses to outbreaks like Ebola in West Africa, which killed at least 11,000 of the more than 28,000 people infected between 2014 and 2016. Working with local authorities, the WHO conducted research into the safety of a recently developed vaccine, which achieved near-perfect effectiveness and helped stem the spread of the disease.

Trump first attempted to leave the WHO during his first term in 2020, accusing the organization of “severely mismanaging and covering up” the spread of Covid-19.

Trump has long said he believes the coronavirus came from a laboratory in Wuhan, China, which Beijing has sought to obscure. The WHO notably shared some of Trump’s concerns and called in December – five years after the first case of Covid-19 was detected – for China to be more transparent to help the world understand how the pandemic began.

During his last election campaign, Trump was more brazen, calling the organization “nothing more than a corrupt globalist scam” that was “shamefully covering the tracks of the Chinese Communist Party.”

By focusing on the origins of Covid-19, Trump underestimated the role that the WHO – led by the United States – played in combating the virus once it began to spread, say the experts.

Alan Bernstein, director of the Global Health Initiative at the University of Oxford, said the WHO played a crucial role in convincing China to disclose the genetic sequence in early 2020, which was the basis of the vaccines developed in the United States.

“You can’t effectively fight a pandemic without some sort of global table where countries around the world can meet and discuss and twist their arms to release data,” Bernstein told CNN.

Trump’s animosity also has a financial aspect. The president has previously said the United States pays about $500 million a year to the WHO, compared to China’s $40 million, despite having a much larger population.

As he signed Monday’s executive order, Trump was asked whether, as president during the Covid-19 crisis, he appreciated the importance of agencies like the WHO.

“Yes, but not when you’re being ripped off like we are,” he replied.

This worldview misses out on the benefits of cooperation, said Devi Sridhar, chair of global public health at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland.

“The United States would be weaker in its national security imperatives if it were not part of the WHO, given that it would not have that cooperation with other countries to know what is happening in terms outbreaks and to help manage the response,” Sridhar told CNN.

It takes a year to fully withdraw from the agency — which is why Joe Biden was able to halt the U.S. exit four years ago, in one of the first acts of his presidency.

But there are signs that the start could be faster this time. Monday’s executive order called on the secretary of state and director of the Office of Management and Budget to suspend funding “with all possible expeditiousness.”

Perhaps anticipating Trump’s departure, the WHO earlier this month issued a funding request for $1.5 billion to address 42 ongoing health emergencies. The organization declined to make that connection in a call with reporters Friday, just days before Trump took office.

Tedros said Tuesday he “regrets” Trump’s decision, emphasizing that the United States also wins because of the agency it contributes to.

“For more than seven decades, WHO and the United States have saved countless lives and protected Americans and all people from health threats. Together, we ended smallpox and brought polio to the brink of eradication. American institutions have contributed to and benefited from their membership in the WHO,” Tedros said.

UCL’s Balloux said the move could delay polio eradication and hamper efforts to combat tuberculosis and HIV.

“It could delay the response to major outbreaks that we are experiencing, like Ebola, and those that we are not experiencing yet,” he told CNN.