You read The briefingMichael Waldman’s weekly newsletter. Click here to receive it in your inbox.

Historians (if they still have any in the future) will view the 2024 election as a time when absurdly wealthy individuals launched themselves into political power.

Elon Musk, the richest person in the world, spent more than 250 million dollars to elect Donald Trump. He was not alone. Venture capitalist David Sacks, casino owner Miriam Adelson and packaging supplies magnate Richard Uihlein all helped Trump with massive financial support.

Rich people have already spent a lot of money on the elections. (George Soros, meet the Koch brothers.) What was unprecedented this time was that they actually financed, and in at least one case helped run, a presidential campaign that otherwise was carried out with limited staff.

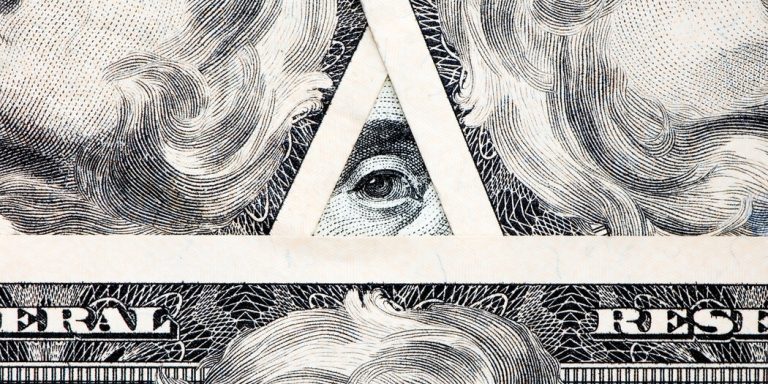

Far more than most people realize, this distorted political world has been given to us by the Supreme Court.

Fifteen years ago next Tuesday, the Court, led by Chief Justice John Roberts, ruled Citizens United v. FEC. By 5 votes to 4, conservative judges overturned a century of campaign financing law. The decision was extremely controversial. In dissent, Justice John Paul Stevens wrote: “Although American democracy is imperfect, few outside the majority of this Court would have thought that its flaws included a lack of corporate money in politics. » A few days later, during the State of the Union address, Barack Obama chastised the robed judges sitting in the front row. “That’s not true,” Justice Samuel Alito said, according to lip readers.

We can now see that the impact of the decision was not less than expected, but greater.

Citizens united didn’t say that businesses are people. Rather, this case and other cases that extended its logic declared that spending on campaigns could not be limited if it was independent and disclosed. Ultimately, the decision resulted in almost complete deregulation of money in federal elections.

Part of the churn over the past 15 years reflects noisy local energy. Raising small funds has been a real democratizing force. But the increase in small donors has been outpaced by the new role of large donors.

According to my colleagues Marina Pino and Julia Fishman, in a analysis released today, “about 44 percent ($481 million) of all the money raised to support Trump came from just 10 individual donors.”

In 2010, I was one of those who feared that Citizens united that would mean Exxon and other giant corporations would dominate spending. This did not happen. Instead, we had a political system dominated by ultra-wealthy individuals to a degree never before seen in American politics.

What about these reservations and quibbles of the Court? The hackneyed fiction that these expenditures are “independent” has completely disappeared. Trump outsourced many campaign operations to so-called independent groups, paid for by Musk – who traveled with and supported the candidate.

When it comes to disclosure, more and more of the funds used in American politics are “dark money,” large donations where the identity of the donor is not disclosed or is hidden behind layers of committees and pseudonyms.

For more than a century, since money began to really matter in politics, we have understood the grave risks to democracy posed by the uncontrolled use of money in campaigns. It’s not that money buys results: after all, Kamala Harris raised $1.5 billion in three months, although it’s unclear whether her need to constantly raise money has affected her unusually lukewarm economic message.

Rather, the main distortion comes from what politicians – those who ultimately hold power – think money does.

We may now be entering a new era in which money merges with power. It is lukewarm to complain that “big donors” have undue influence over government. The biggest donors now lead the campaigns. These are not behind-the-scenes financiers or oil and gas enthusiasts, but large government contractors and, in Musk’s case, the owner of one of the world’s largest media properties. Shortly after Election Day, Musk moved in a cottage with the president-elect.

Now he and other major Trump donors will be able to shape administration policy in important areas like tariffs, tax cuts and government procurement. And indeed, the late influx of money from tech moguls has transformed the new Trump administration’s governing agenda. Did MAGA voters vote for the $2 trillion cut in federal spending that is supposedly the product of Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy’s DOGE (Department of Government Efficiency) blue commission?

At the turn of the 20th century, Americans grappled with similar issues of wealth and power. When JP Morgan faced an antitrust lawsuit, he told the president, “If we’ve done something wrong, send your man to my man and they can fix it.” » Theodore Roosevelt had a different approach during another period of corruption and reform. “Sooner or later,” he told a reporter, “unless there is a readjustment, there will come a tumultuous, wicked, murderous day of atonement.” »

We must develop a new reform program to respond to this major change in our policy. Passing federal bills requiring full disclosure from large donors, reining in super PACs, and demanding that laws still on the books be actually enforced is necessary, but not sufficient. Reversal Citizens united and as soon as possible Buckley v. Valeo case (by constitutional amendment or otherwise). A more robust system of public financing by small donors, like the one that recently debuted in New York State. Other creative reforms, of the type that marked a democratic response to corrupt governance. Everything is necessary.

And we need to find a new language to understand and describe what is really happening. It’s not just the same “cash for access” economy that we’re used to. It’s something bigger, more worrying, more consequential. And this is a world that the Supreme Court has given us.