In the 1980s, mysterious noises in the ocean almost upended international peace. We were in the middle of the Cold War and tensions were high between Sweden and the Soviet Union. When Swedish navy ships began picking up strange underwater signals, military leaders thought they were enemy submarines invading their waters.

The truth, like explained by Magnus Wahlberga bioacoustics expert involved in the government’s investigation into the matter, was far stranger. The mysterious noises were actually herrings, giant schools emitting streams of fish farts loud enough to trigger underwater SONAR systems.

SCROLL TO CONTINUE READING THIS POST

Later research shows that herring emit bubbles from their swim bladders for many reasons: when frightened, to regulate their buoyancy in the water, and potentially to communicate. These fish emit different bubble patterns at night, leading researchers to speculate that farting might be a way for the schooling fish to stick together in the dark.

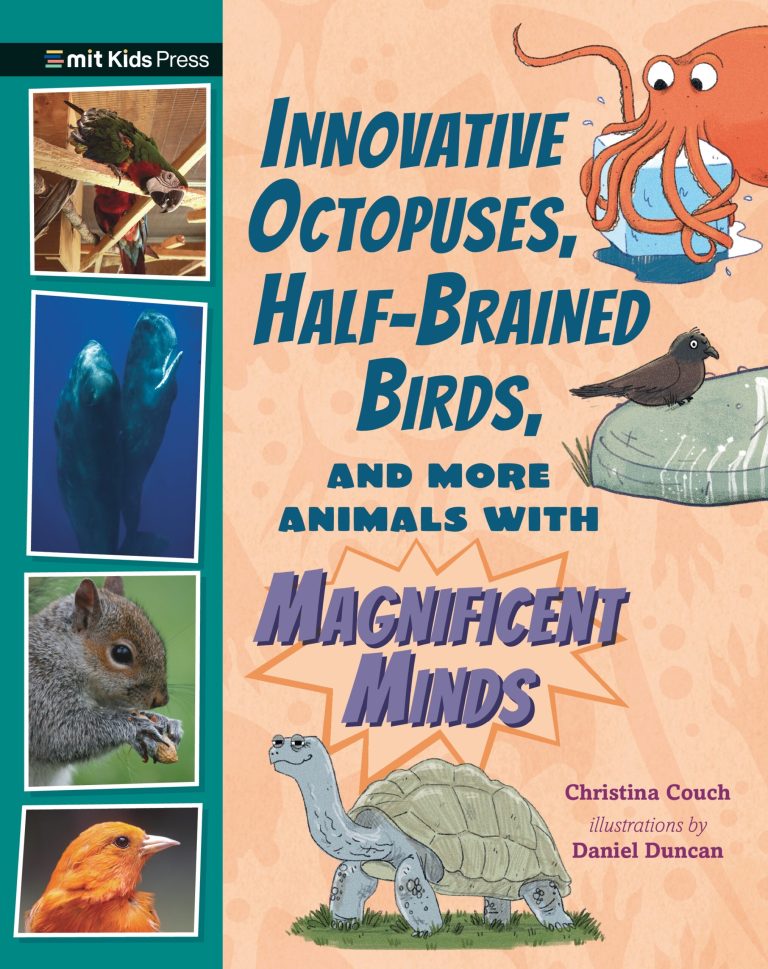

I discovered flatulent fish while writing Innovative octopuses, half-brained birds and other animals with magnificent mindsthe third book in the Extraordinary Animals series from MIT Kids Press. Written for middle grade readers, the book delves into the neuroscience behind some interesting and unique things animals can do with their brains – things like sleeping with half their brain alert, creating complex means of communication, and maintaining their cognitive functions for hundreds and hundreds of years. years. It also explains how these neuro-talents integrate with similar processes in your mind and offers activities kids can do to challenge their own brains.

Fish that fart — and the researchers curious and quirky enough to study them — are a big part of why I love being a science journalist. While science has a well-deserved reputation for being precise, analytical and perfectionist, it is also extravagant, imaginative, wildly flawed and often hilarious, just like young readers themselves and older ones who, like me, have the impression that adulthood is more about age. a costume than an appropriate identity.

For many of us who are not naturally inclined toward science or who are intimidated by it, these qualities can be vital gateways to worlds of research that otherwise seem inaccessible. As a child, I was never good at science. The carefully executed formulas and experiments seemed intended for people who were smarter, more focused, and more easily mastered mathematics and mechanics. I was a die-hard theater kid, happiest when slipping into dream worlds on stage, in books, or writing them out on my own – the weirder and crazier, the better. Offstage, I delved into STEM classes, always two steps away from others and dependent on generous classmates and teachers to answer what seemed to me to be the stupidest, most basic questions in the world.

What I didn’t realize at the time was that many of these experiences would provide very important training for my future career. Inasmuch as science journalistmy job is to find interesting and unique stories that help all readers – those who love science and those who don’t – understand and contextualize the science happening around them. This often means asking experts to break down their research into simplistic terms: A question I frequently ask when reporting is, “Can you explain this concept to me as if I were a third grader?” I constantly feel light years out of my league.

This suits me and instead of seeing it as a weakness, I’ve come to view it more as a surprising superpower. In many ways, I act as a translator between researchers and readers. If experts can teach me how humans create memories, why an octopus’s arms can make certain decisions on their own (no brain processing needed), or how PTSD affects animals and humans – this that I talked about in this book – I can explain it. to you, a child or anyone else, without any alienating academic jargon.

I also came to view my own scattered ping-pong brain and my love of strange things as strengths: ways of making connections between science and other fields and attracting readers who might not don’t necessarily care about what happens in a laboratory. Building on the qualities that made science so intimidating when I was young has led me to places that are fascinating for adult readers:the turbulent world of anchovy sex, a cat cemetery owned by a man who believes he’s found the feline fountain of youthAnd a conversation with a robotic human head who is afraid of clownsjust to name a few. For children’s media, I’ve found that engaging with this content helps spark conversations between young readers and the adults around them. It’s exciting every time someone tells me that their child learned a surprising fact about animals in my book or participated in one of the science activities and they just can’t wait to share it.

I wrote Innovative octopuses, half-brained birds and other animals with magnificent minds (And co-wrote another book in the Extraordinary Animals series) for science-minded readers and for curious children who are full of questions about the world around them but have not yet found their way to science. In writing this book, it was important to me to feature a diverse set of researchers, inside and outside the lab, ranging from a geneticist who analyzes ancient DNA to uncovering long-lost stories about a isolated island to a fish fossil scientist who is also an aerial circus performer. It was also important to tell stories of people who are not scientists. For example, the chapter I enjoyed writing the most centers on a U.S. Army veteran who works at a bird sanctuary teaching humans who have experienced trauma how to work with parrots who have also suffered trauma.

SCROLL TO CONTINUE READING THIS POST

I hope young readers leave the book knowing that no matter what they are interested in, the science is there too and you don’t have to be a certain type of person to explore it. Science makes you think, but like art or literature, it can also make you laugh, dream, see and appreciate the world, or even just your own brain, in new and exciting ways.

Meet the author

Christina Couchest author of Innovative octopuses, half-brained birds and other animals with magnificent minds (MIT Kids Press, 2024), a book on the extraordinary neurology of animals, and co-author of Detector dogs, dynamite dolphins and other animals with sensory superpowers (MIT Kids Press, 2022), which focuses on animal sensory biology. She is also the associate director of MIT’s Graduate Program in Science Writing and a lecturer in the program. Projects she has worked on for children and adults have won the AMBA Educational Innovation Award, a Buzzie Award from the World Congress of Science and Fact Producers, and honors from the Virginia Press Association. His writings can be found in Atlas Obscura, Discover Magazine, Fast Company, Hakai Magazine, Mental Floss Magazine, MIT Technology Review, The New York Times, NOVA, Science Friday, Smithsonian, The edge, Vogue.com, and elsewhere.

Links

Visit me online at couchwins.com or on social networks at ohyeahitscouch.bsky.social or on LinkedIn.

About Innovative octopuses, half-brained birds and other animals with magnificent minds

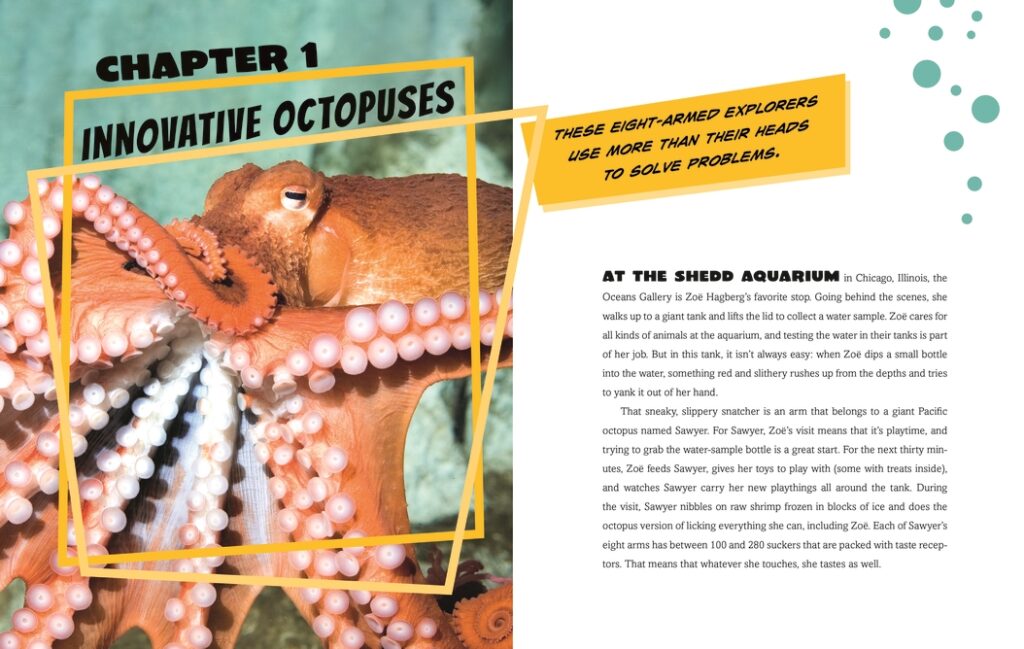

At a Chicago aquarium, an octopus breaks a block of ice to try to get frozen food inside. His brain makes most of the decisions, but his suction cup-covered arms make some choices on their own. A bird nesting in the high rocky cliffs of Hawaii takes a short nap before heading out to hunt. Even when she sleeps, half of her brain remains awake. In a very special garden in California, a squirrel decides where to hide its food for the winter. She uses mental tricks to remember her hiding places. And as you read this, a wonderful and mysterious organ inside your skull is working day and night to give you amazing abilities.

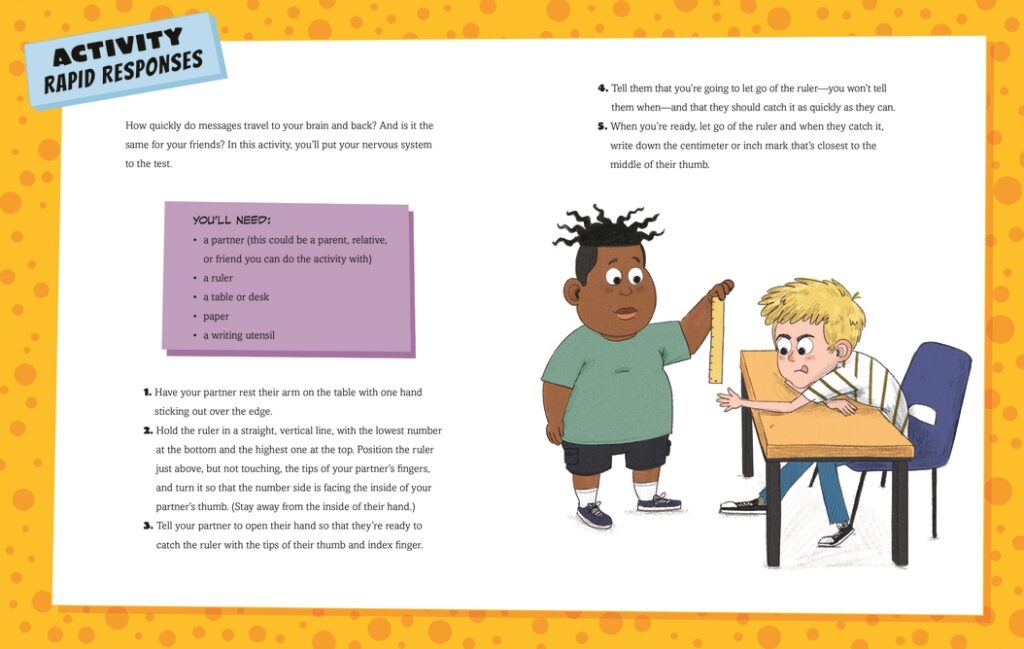

In this book, you’ll discover six animals with incredible brain talents and delve into the science behind these superpowers. You’ll also meet the people who study these creatures and learn about the strategies they use to try to unlock the brain’s many secrets, and you’ll learn about some of the things that happen between your own ears. Plus, you can challenge your mind with activities at the end of each chapter. So put your thinking cap on and get ready to explore the most extraordinary organ in the animal kingdom.

ISBN-13: 9781536229721

Publisher: Candlewick/MIT Kids Press

Publication date: 01/14/2025

Series: Extraordinary Animals

Age range: 9 to 12 years old

Filed under: Guest post