In 2012, Deborah Cory-Slechta of the University of Rochester in New York was given a “bucket of brains.” A colleague had studied how air pollution around the university damaged the hearts and lungs of mice and asked Cory-Slechta to check whether the animals’ brains were damaged. As an expert on lead neurotoxicity, Cory-Slechta remembers thinking, “Air pollution? How bad could it be? But what she saw in these brains was so “staggering,” she says, that it completely changed the direction of her research.

Focusing on the harmful effects of air pollution on the brain1 landed Cory-Slechta in solitary territory. It is well established that air pollution, in the form of particulate matter, ozone or other toxic gases, contributes to asthma, lung cancer and other respiratory diseases, and that particles particularly contribute to heart disease2. But at the time, she says, few people studying air pollution were interested in the brain — and even fewer neuroscientists were interested in air pollution. Her presentations attracted so little attention at neuroscience conferences that she stopped attending the meetings.

Today, this area of research is attracting increasing interest and concern around the world.3. Study after study has shown that higher levels of air pollution are correlated with increased risks of dementiaas well as higher rates of depression, anxiety and psychosis4. Researchers have also found links to neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism, and cognitive deficits in children.5.

Microsoft’s lightning-fast AI is the first to predict air pollution around the world

In 2020, the influential Lancet Commission on Dementia recognized air pollution as a risk factor for the disease.6and in its follow-up report from last year7 he said exposure to airborne particles “is now of great concern and interest.” Meanwhile, a 2022 report8 of the UK Government’s Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollutants has called for more research into the links between air pollution and dementia. Similarly, the 2021 global air quality guidelines from the World Health Organization (WHO) highlighted the importance of studying the neurological effects of air pollution on young people and adults. elderly people.9.

The WHO estimates that 99% of the world’s population is exposed to pollution above recommended levels, and that many cities in low- and middle-income countries have particularly poor air quality. But it’s not just about megacities like Mexico City and Delhiwhere people face risks. “Even low exposure that people think is safe enough for public health has an effect in the brain,” says Megan Herting, a neuroscientist at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

Researchers now need to try to understand the mechanisms behind these problems in order to take steps to mitigate them, says Ian Mudway, an environmental toxicologist at Imperial College London and co-author of the 2022 UK report. Mudway, the million dollar question is: “What about air pollution is causing these effects?” »

Make the connections

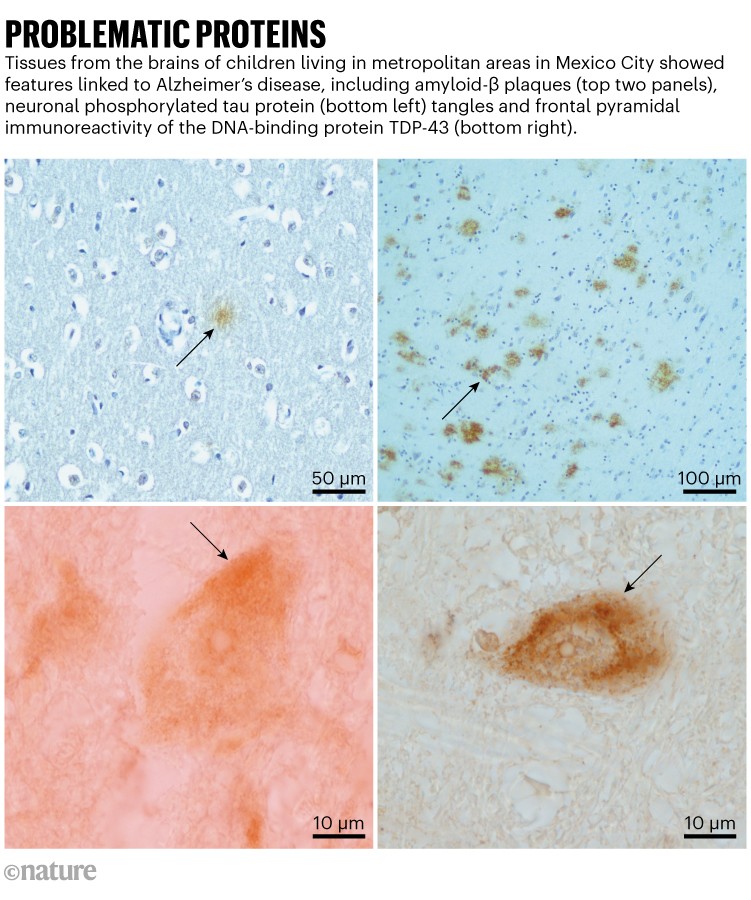

Studies conducted on the brains of children and dogs in Mexico City in the late 2000s and early 2010s were among the first to sound the alarm about the neurotoxicity of air pollution. Neuroimaging revealed that many more children living in the highly polluted city had damage in the white matter pathways that connect brain regions than children living in less polluted areas, with the prefrontal cortex appearing particularly vulnerable. And urban children, without other risk factors for brain disorders, performed relatively poorly on cognitive tasks.10 (see “Problem Proteins” for more results).

Source: L. Calderón-Garcidueñas et al. Int. J. Approx. Res. Public health 311568 (2021)/(CC-BY-4.0)

Pollution is an extremely complex mixture of gaseous and particulate components that differ depending on the source. Vehicle exhaust and industrial manufacturing are important sources of particles of various sizes, and cookers, forest fires and desert dust also contributes. Fuel combustion and other sources release nitrogen and sulfur oxides, carbon monoxide and ozone. Studies in several countries, including those where regulations have Significantly improved air quality In recent decades, associations have been found between pollution and specific brain disorders.

A 2023 analysis of more than 389,000 UK Biobank participants showed that long-term exposure to airborne particulate matter, nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide was correlated with levels higher rates of depression and anxiety.11. Lead author Guoxing Li, an environmental toxicologist at Peking University in China, points out that even very low levels of exposure increase the risk of these conditions.

Last month, a 16-year study of more than 200,000 people in Scotland found that higher cumulative exposure to nitrogen dioxide was associated with increased hospitalizations for mental health and behavioral disorders.12.

Meanwhile, studies in France, the United States and China have shown that in regions where air quality has improved, rates of dementia, cognitive decline and depression have decreased among older populations. .7.

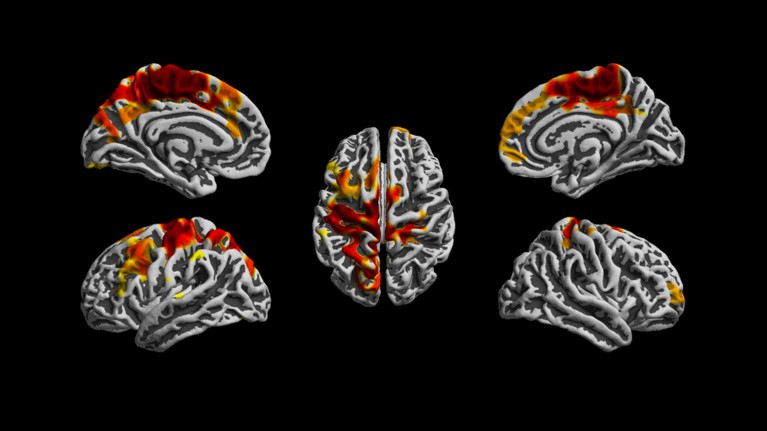

Observational studies have also linked air pollution to structural changes in the brain, such as a reduction in hippocampal volume, which correlate with an increased risk of dementia in older adults.13. And Herting’s studies of neuroimaging data from the developing brains of thousands of young people across the United States suggest that air pollution disrupts the development of white matter pathways. Last year, his team reported that increased exposure to air pollution appears to impair communication between brain regions.14.

But such studies have yet to converge on a clear trend in damage, Herting says. She suspects that the timing of exposure during development could shape vulnerability.

Despite all the evidence linking air pollution to brain damage, researchers say it’s difficult to determine the clear cause using observational studies alone. For example, people from poor communities, who often breathe the worst quality airare likely to have more risk factors for brain disorders, stress, low educational attainment and obesity, compared to those in higher income areas. And many existing studies estimate exposure based on residential addresses, without considering how individuals’ occupations and lifestyles shape their exposure.

How air pollution causes lung cancer – without harming DNA

The specific types of pollutants people breathe almost certainly matter, researchers say. Standard air quality measurements are based on levels of primary gaseous components and particles less than 10 micrometers in diameter (PM10) or 2.5 micrometers (PM2.5). But airborne particles carry a range of chemicals, from simple salts to countless highly toxic compounds, which vary depending on location. “All particles are treated as equally toxic,” says Mudway, “and yet they are an assortment of all the chemicals – hundreds of thousands of chemicals – in the air.”

Additionally, ultrafine particles are not systematically monitored, notes Cory-Slechta. Yet particles less than 100 nanometers in diameter are the most chemically reactive airborne particles and most likely to enter the body and brain, she says.

Even without this gap in monitoring data, Mudway says, observational studies of people breathing many pollutants cannot isolate the responsible chemicals to provide mechanistic understanding. Cardiovascular disease is a known risk factor for dementia. Thus, the damage caused by air pollution to the heart and blood vessels is another confounding factor. “The only way to solve it,” says Mudway, “is through experimentation.”

In the laboratory

Laboratory studies can show, for example, that under controlled conditions, actual cocktails of air pollutants harm the brain. This is what Cory-Slechta found in 2012, when she compared the brains of mice that had breathed the university’s ambient air with those that had breathed filtered air. Subsequent studies in his laboratory found that mice exposed to ultrafine particles during development – including in the womb, from their mothers’ breathing – had enlarged white matter tracts and cerebral ventricles.15. Mice exposed during development subsequently showed greater impulsivity and short-term memory deficits.

Physical changes in the brain partly overlap with those in people with neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism and schizophrenia. In older animals, air pollution appears to accelerate the deposition of amyloid and tau proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Other animal studies have revealed damage at the anatomical, cellular and molecular levels.

Brain scans show areas of reduced cortical thickness (colored regions) in children exposed to higher levels of road pollution during their first year of life.Credit: T. Beckwith et al./PLoS ONE (CC-BY-4.0)

Although the signs of damage vary from study to study, Caleb Finch, who studies aging at the University of Southern California, says there is one common facet: “It’s an inflammatory response,” he said. Studies from his lab and others show that genes that mediate inflammatory responses are activated; messengers associated with inflammation become more abundant; there are signs of oxidative stress; and microglial cells that detect damage and protect neurons are activated. All major classes of brain cells are affected, Finch explains.