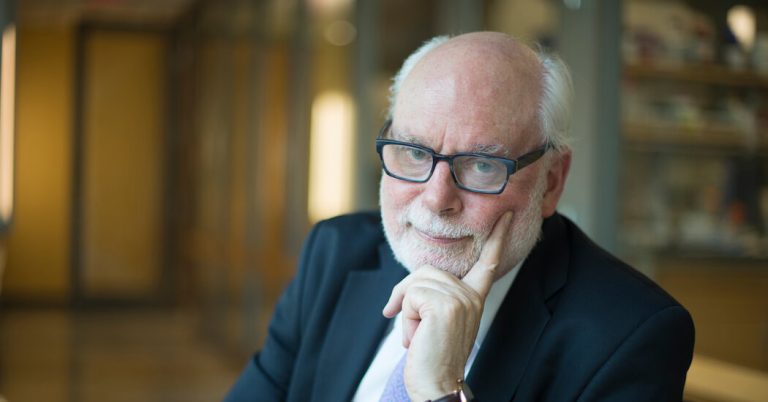

J. Fraser Stoddart, a Scottish-born scientist who went from playing with construction toys as a child to building molecular machines a thousand times smaller than the width of a human hair, known as nanomachines , for which he shared the 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. , died on December 30 in Melbourne, Australia. He was 82 years old.

Alison Margaret Stoddart, his daughter, said he died of cardiac arrest in a hotel while visiting his other daughter, Fiona Jane McCubbin.

Dr. Stoddart and his colleagues, Jean-Pierre Sauvage of France and Bernard L. Feringa of the Netherlands, were the first to understand how to build molecules with physical rather than chemical bonds. These molecules could move freely and became the building blocks of nanomachines. The most basic, called catenanes, are interlocking molecules, like links in a chain. They were synthesized for the first time by Dr Sauvage in 1983.

In 1991, Dr. Stoddart and his team took a big step forward: they created molecules called rotaxanes, whose ring-shaped molecules are wrapped around other dumbbell-shaped molecules. The ring molecule slides back and forth on the dumbbell, the ends of which prevent the ring molecule from sliding. (The word rotaxane comes from Latin roots meaning wheel and axle.)

Dr. Stoddart then figured out how to slide the ring molecules between two set points, like a miniature switch, and then how to put three rotaxanes together to create a platform capable of moving up and down 0.7 billionths of a meter – roughly , a molecular elevator.

Since these early successes, scientists have been able to build molecular machines that contract and expand, replicating the actions of muscles; tiny propellers driven by light energy; and, in 2011, a small molecular car with four-wheel drive, although it is only a few billionths of a meter long.

These devices have so far had few practical applications. But in announcing the prize, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences compared their potential to that of an earlier revolution.

“In terms of development,” the academy said, “the molecular motor is at the same stage as the electric motor in the 1830s, when scientists were showing various cranks and spinning wheels, unaware that they would lead to trains electrics, washing machines, fans and food processors.

Dr Feringa said a very likely application would be tiny robots that doctors could inject into patients to find and destroy cancer cells or to administer drugs.

Dr. Stoddart also used his expertise to try to find solutions to other problems.

In 2021, he co-founded H2MOF, a hydrogen storage and transport company, with Omar Yaghi, another renowned chemist. Hydrogen, a clean fuel that could reduce greenhouse gas emissions, is notoriously difficult to transport and store. The company uses technology based on molecular materials developed by Dr. Stoddart and Dr. Yaghi, which allows hydrogen to be stored and transported in a solid state at room temperature and low pressure. This technology could help make hydrogen a more practical clean energy source.

And in 2019, Dr. Stoddart launched a skincare brand called Noble Panacea, based on porous organic nanovessels that he and some of his students developed. These containers are said to protect skin care products from degradation or contamination by light, oxygen and water, making them more effective.

“I guess it’s obvious that I’m not a typical skincare brand founder,” Dr. Stoddart told Vogue. “Ten years ago, my team and I did not specifically expect to discover technology with applications for skin care. But inventing things with the aim of having a positive impact on people has always been my intention. »

James Fraser Stoddart was born on May 24, 1942 in Edinburgh. He was the only child of Thomas Fraser Stoddart, a farmer, and Jane (Fortune) Stoddart, who owned a small hotel in Dunbar before her marriage.

The family moved to a farm called Edgelaw, just south of Edinburgh, when James was six months old, and he lived there until he was 25. They farmed and raised livestock, but they had no electricity. During cold winters, the family often gathered in the kitchen to stay warm. In his Nobel biographyDr. Stoddart called it “a very simple way of life.”

Among his rare diversions were Meccano sets, miniature construction kits popular in Britain at the time, which he could use to build gadgets. He also became a mechanic; he learned to take car and tractor engines apart to clean and repair them, then put them back together.

At the age of 8, he left his small village school to attend Stewart’s Melville College, an elite boys’ school in Edinburgh. He attended the University of Edinburgh, where he focused on mathematics and science, particularly organic chemistry. During his third year, his professor hired him to be part of a research group studying the structural complexities of acacia plant gums. This set him on his path.

He graduated in 1964 and later completed his doctorate. in two years.

While at the University of Edinburgh, he met a brilliant fellow student named Norma Scholan. They married in 1968 and had two daughters. Fiona and Alison followed in their parents’ footsteps, achieving top honors and doctorates in chemistry, Fiona from Imperial College London and Alison from Cambridge University.

Norma Stoddart died in 2004. In addition to her daughters, Dr. Stoddart is survived by four grandsons and one granddaughter.

Dr. Stoddart carried out postdoctoral research at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, then returned to England to work as a researcher at the University of Sheffield. He joined the faculty in 1970.

In 1978, he was hired as a researcher by Imperial Chemical Industries, a British chemical company specializing in the manufacture of herbicides. It was there that he began to imagine how it would be possible to build molecules with physical bonds. In his Nobel interviewhe said his idea came in part from the characteristics of the chemicals the company used to make its fertilizers.

Until then, researchers had attempted to synthesize catenanes by “matching similar types of chemicals.” The success rate was less than 1 percent. But the herbicide factory was successfully combining ingredients from different chemical families, and Dr. Stoddart realized that this could be the key to designing catenanes.

He had the right idea, but it remained difficult, and Dr. Stoddart and his colleagues encountered skepticism from other scientists who doubted even the possibility of nanomachines. It will take another decade before they succeed.

After three years at ICI, Dr Stoddart returned to Sheffield, where he continued his research.

In 1990, he was hired by the University of Birmingham, where he synthesized rotaxane for the first time. In 1997, he accepted a position at the University of California, Los Angeles, and in 2008 he was hired by Northwestern University, which established a nanotechnology research institute, the Stoddart Mechanostereochemistry Group, in his honor.

In 2023, he was recruited by the University of Hong Kong. He was working there when he died.

In addition to the Nobel Prize, Dr. Stoddart received the Albert Einstein World Science Prize in 2007. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 2006.

During his career, Dr. Stoddart has mentored and supervised the doctorates and research of more than 400 students from 43 countries. But he treated them more like partners than sidekicks.

“I recognized that you have to build a team and allow the brains of 30 people to work on something rather than a top-down approach where you say I have all the ideas and it’s just pairs of hands or slaves,” he said. Nobel said in his interview. He added: “I rebel against the hierarchical system that hit me at the start of my career and I said I’m not going to go down that path. I will shape something new and I will allow incredibly talented young people to express their creativity.