I came into this world the same year that Jimmy Carter was elected the 39th President of the United States. About 18 years later, I had the honor of meeting Carter when he was a freshman at Emory University, where he was a professor. Today, I said my most sincere farewell to Carter at his state funeral, where I was moved to tears by numerous eulogies, including one written by Gerald Ford before his death and delivered today today by Ford’s son. Although they were political rivals in the 1976 election, Carter and Ford later became deep friends – a beacon of hope in our hyperpartisan politics. “Jimmy, I look forward to our reunion,” Ford wrote. “We have a lot of catching up to do.”

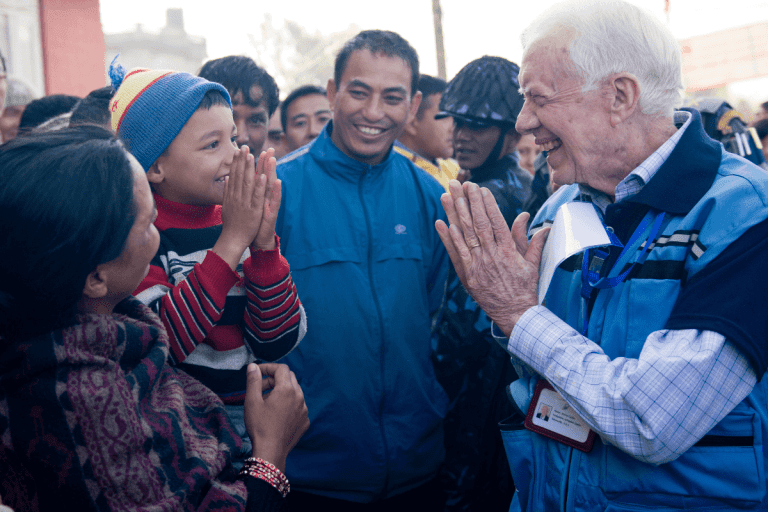

When I first met Carter, he was well into his distinguished post-presidential career as a diplomat, humanitarian, and advocate for public health, human rights, and global democracy. He and his wife, Rosalynn, had founded the Carter Center in partnership with Emory more than a decade earlier. But despite the other demands on his time, Carter held an annual public forum with the freshmen, and I was deeply impressed by the way he responded to our barrage of questions with great humility, frankness, intelligence and often humor. Although I don’t remember his specific responses, I still have a vivid memory of coming away from the event convinced that Carter was a person of deep moral character and a tireless commitment to justice and of peace.

I was so inspired by Carter’s remarks that I decided to apply for an internship in the Carter Center’s Conflict Resolution program. I was an intern there for two years and although my interactions with Carter as an intern were rare, I had the honor of contributing to a weekly update on conflicts around the world that was not only shared with Carter himself, but also (I was told) shared with an esteemed group of peace and human rights veterans from around the world that Carter helped bring together.

Since his death, Carter’s remarkable life and many accomplishments have been rightly celebrated, including the Camp David Accordsa history nuclear weapons treatymajor environmental protection legislationthe exit of political prisonersthe virtual eradication of the guinea wormdriving assistance free and fair elections in dozens of countries around the world, and decades of volunteer service with Habitat for Humanity. But despite this impressive legacy, what inspires me most about Carter is the way he applied his faith to the messiness of politics, both during his tenure in the White House and over the many years that followed – a model we desperately need today in our increasingly polarized society. and vitriolic politics.

During his campaigns and presidency, Carter was extraordinarily open about how his born-again faith influenced his public life. In his inaugural speech in 1977, he cited Micah 6:8 at the beginning: “He has shown you, O man, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God. He made it clear then that his faith was inseparable from his view on political issues and how that would lead him to govern as president. According to the Washington Posthe “once told an interviewer that on hectic days he could pray up to 25 times.” Despite the overwhelming demands of the position of president, Carter not only attended church regularly, but also found time to teach Sunday school – which still amazes me. In a 1978 audio recording, Carter said a Sunday school lesson: “God will supply all your needs with His unlimited riches and glory through Jesus Christ. That’s a good promise. It’s a good campaign slogan. And it’s so good that many people don’t believe it. But we know it’s true.

I admire these and other ways in which Carter authentically communicated how his faith shaped his values and worldview, while maintaining a strong commitment to religious pluralism and religious freedom. Although no party has a monopoly on faith, today’s Democratic Party – which has often been reluctant to talk about faith – as well as today’s Republican Party – which often acts like s he possessed faith – could learn much from Carter’s example.

But while Carter’s image As a born-again Southern Baptist Sunday school teacher who promised never to lie to the American people, he was liked by many evangelical voters in 1976. That same faith also inspired Carter to take bold – and sometimes unpopular – positions. His understanding of his faith also led him to stand up to his fellow evangelicals when he disagreed with their theological conclusions. For example, in 2000, he severed its affiliation with the Southern Baptist Convention on his stances on gender equality, saying their ban on female deacons and other policies “violate the fundamental premises of my Christian faith…Personally, I believe the Bible says that all men are equal in the eyes of God . Personally, I believe that women should play an absolutely equal role in serving Christ in the Church. He also told the Huffington Post in 2015: “I think Jesus would encourage any love affair if it was honest and sincere and didn’t harm anyone else, and I don’t see same-sex marriage harming anyone else.”

Carter also applied his faith to politics within the Baptist tradition that he and I share. Carter was dismayed by the deep racial and ideological divisions which has embroiled the Baptist world, undermining Christian unity and the ability of the Church to serve others, especially the disenfranchised. In response, Carter used his public profile to convene Baptist leaders and foster unity among Baptist denominations across the New Baptist Covenantan initiative that brought together 30 organizations representing 20 million Baptists from across racial and political backgrounds. Although the initiative has made significant progress in building relationships and unity within the Baptist community, the largest Baptist denomination, the Southern Baptist Convention, has largely criticized or kept the initiative at arm’s length.

Jimmy Carter’s presidency marked a key turning point in the political allegiances of many white evangelicals in the United States. Carter won the presidency in 1976 with 51 percent of the evangelical vote, only to lose it decisively four years later to Ronald Reagan. Several factors within Carter’s presidency impacted this shift among voters, including a IRS decision refuse tax exemptions to private religious schools who were not racially integrated and foreign policy crises Which, according to some voters, showed that Carter was ineffective in protecting American power in the midst of the Cold War.

But the shift among evangelical voters was also greater than Carter’s: After Carter’s presidency, most white evangelicals seemingly left behind the commitment to social justice and peace that had permeated the Carter’s faith throughout his life. They chose instead to merge their faith with a narrow conservative agenda and an allegiance to the Republican Party, a shift that intersected with the Republicans’ southern strategy and the then-ascending religious right. Today, these strategies to unite white Christian voters behind the Republican Party have morphed into the current Christian nationalist movement that helped propel President-elect Donald Trump to the White House. We can only imagine what the trajectory of the country and the evangelical movement would have looked like if white evangelicals had embraced more of Carter’s faith and priorities rooted in Matthew 25.

In Faith: a journey for everyone, Carter writing: “Most church members are more self-satisfied, more attached to the status quo, and more exclusionary of people who are different than are the politicians I have known. » Carter demonstrated throughout his life and career how our faith should be an active faith that impacts and even transforms our community and our world. He showed how our faith should influence and inspire our politics, rather than the other way around. As our nation and the world honor Carter’s legacy, I hope his unwavering faith will serve as an inspiration to everyone on how we can be salt and light, advancing and protecting the dignity and rights of man in our broken and wounded world.