It was easy to miss the rapid movements of Dr. Robert Gray, tapping his smartphone screen at the beginning and end of patient visits on a recent day.

But Gray said those quick finger taps changed his life. He used an app that records discussions during his appointments, then uses artificial intelligence to find relevant information, summarize it and zap it, in seconds, into each patient’s electronic medical record.

The technology meticulously documented each visit so Gray wouldn’t have to.

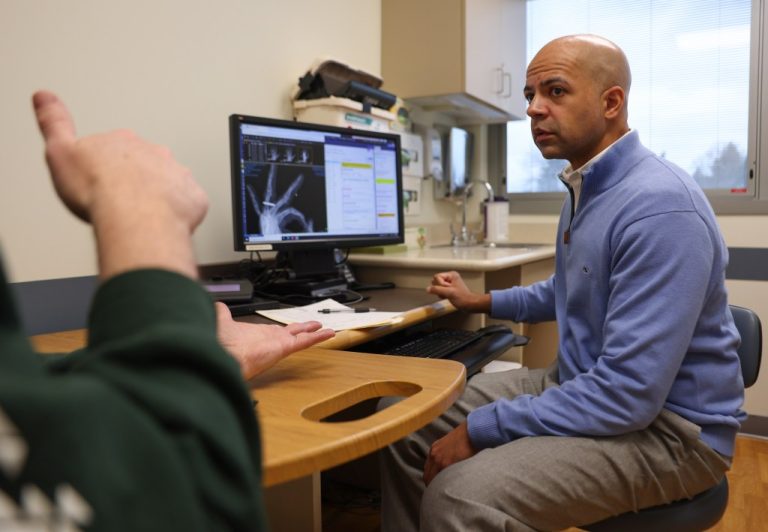

“I enjoy working a lot more,” said Gray, an Endeavor Health hand surgeon. He no longer tries to consult with patients while summarizing visits on a computer. “I don’t feel like I’m getting hit by a truck every day.”

It’s a technology that’s quickly spreading to doctors’ offices in the Chicago area and across the country, and could soon become a standard part of medical appointments. Local healthcare leaders hope the technology will help combat physician burnout by significantly reducing the time doctors spend on documentation, and they hope it will improve the patient experience. Doctors will be able to spend more time looking their patients in the eyes, rather than staring at computer screens during appointments, health care officials say.

“It allows them to go home to be with their family or focus entirely on the patient,” said Dr. Nadim Ilbawi, medical director of Ambulatory Innovation System at Endeavor.

About 50 Endeavor doctors and primary care specialists have been using the ambient listening technology, made by a company called Abridge, since September.

Other local health systems have taken AI generative note-taking technologies even further.

Northwestern Medicine has about 300 of its doctors using similar technology offered by Microsoft called DAX Copilot, and Rush University System for Health has about 100 clinicians using DAX Copilot as well as technology designed by another company. At UChicago Medicine, approximately 550 clinicians use Abridge technology and approximately 1,300 providers use DAX Copilot at Advocate Health Care in Illinois and Aurora Health Care in Wisconsin. Beyond Illinois, health systems Kaiser Permanente and Johns Hopkins Medicine are among those that have agreed to offer Abridge across their systems.

Today, these technologies are primarily used in the Chicago area during patient appointments in offices and clinics, but several local systems plan to soon offer them to doctors in emergency rooms, emergency care emergency, nurses and those who care for inpatient patients. spend the night in hospitals. Systems executives say that, so far, they have seen positive results from using these technologies, and some say they hope to eventually offer them to all of their vendors.

“This is going to become ubiquitous very soon,” said Dr. Nirav S. Shah, deputy director of medical informatics for AI and innovation at Endeavor.

So far, health systems say the practice is optional for doctors and have no plans to require providers to use it. It is also optional for patients.

Typically, the doctor or medical staff member will ask the patient for permission to use the technology at the beginning of the appointment. Typically, if the patient says everything is fine, the doctor will access it through an app on their phone. The doctor can tap on their phone screen and the app will start recording.

The Abridge app records the audio of the conversation and then transcribes it. The transcription is then sent to a cloud: neither the transcription nor the recording is stored on the doctor’s phone. Artificial intelligence sorts out relevant parts of the conversation, such as discussions of medical and socio-economic issues, small talk and other irrelevant parts, creating notes about the appointment in the patient’s electronic medical record.

The doctor then reviews the notes in the medical record, ensures they are accurate, and may make changes before signing them. The audio or transcript of the appointment is ultimately destroyed, leaving behind only the medical records.

So far, Gray said no patient has said no to the technology. Dr. Douglas Dorman, a family physician at Advocate Health Care in Yorkville, said fewer than 10 patients have rejected the idea since he started using the technology.

Catherine Gregory, who saw Gray recently after undergoing surgery for a broken arm, said it seemed like a good idea to help doctors give their patients more of their undivided attention.

“I’m for it,” said Gregory, 62, of Chicago, “because I want his attention to be on me, especially if I’m in pain, like today.” I don’t want you to miss everything I say about the pain I feel.

Patient Robert Johnston, 61, of West Rogers Park, said he had never heard of the technology before visiting Gray. At first, he worried it would be intrusive, especially if he was discussing a sensitive topic with a doctor. But he said he also sees how it could help doctors and patients have better relationships.

“It’s much better when they can talk to me directly,” he says of doctors. “As long as the privacy issues are protected, I think it’s a great idea.”

Local health systems said the companies they choose to provide the technologies must meet security and privacy requirements for the systems. Violations and cyberattacks have become commonplace in health systems across the country in recent years.

“We take security very, very, very seriously, so it’s definitely been rigorously evaluated,” said Dr. Betsy Winga, vice president of medical informatics and director of medical informatics for Advocate Health Care and Aurora Health Care.

She said she couldn’t discuss the costs of the technology, but said: “The benefits we’ve gotten from it, from a clinician experience perspective, are just invaluable.” »

Overall, Dorman, along with Advocate, said patients seem to like him — or at least what that means for their interactions with him. Patients told him he seemed more relaxed and less stressed, he said.

“I can come back to work every day refreshed, recharged and excited to be there,” Dorman said. “I definitely think it improves my behavior.”

Doctors who have used this technology say that, in some ways, it has helped them return to an earlier era of medicine, when they did not have to spend as much time on documentation. A federal law passed in 2009 encouraged the use of electronic health records as a way to make records more easily accessible, increase patient privacy and improve patient safety. Later, the federal government began penalizing providers who did not use them significantly. Doctors say that over time, the amount of information they have had to enter into records has increased.

In many cases, this leaves doctors with two choices: either try to document patient visits during their appointments, or finish their documentation at the end of the day, which can often mean hours of additional work.

According to an American Medical Association survey, doctors reported in 2023 that they worked an average of 59 hours per week, and nearly eight hours of that time was spent on administrative tasks. About 48% of physicians responding to the AMA survey reported experiencing at least one symptom of burnout.

Doctors and health care managers refer to time spent on administrative tasks outside of the workday as “pajama time.” Northwestern saw a 17% decrease in time spent in pajamas among its clinicians who used AI note-taking technology, and Advocate Health Care saw a nearly 15% reduction.

Dorman, at Advocate, said he spends 20 to 25 hours a week working on documentation, outside of normal hours. He said he was the last to leave the office each day. Today, he says he spends about 30 minutes a week on this task. He said the technology was “life-changing”.

Before technology, Dr. Melissa Holmes, a pediatrician at Rush, would type some of her notes during the day and some in the evening at home after her children went to bed. She said she still works evenings, but it takes her much less time to check and edit the AI’s notes than it does to type all of her own notes.

Technology has also helped her be more present with her patients, she said.

“Before, I felt a little tied to my computer screen because I didn’t want to miss anything,” said Holmes, who also serves as deputy chief medical information officer for the system. “Now when a parent reports something that concerns them about a child, I can be at the parent’s bedside and review it with the parent rather than typing it out and then looking at it.”