Register for the Wonder Theory Science newsletter from CNN. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific progress and more.

Cnn

–

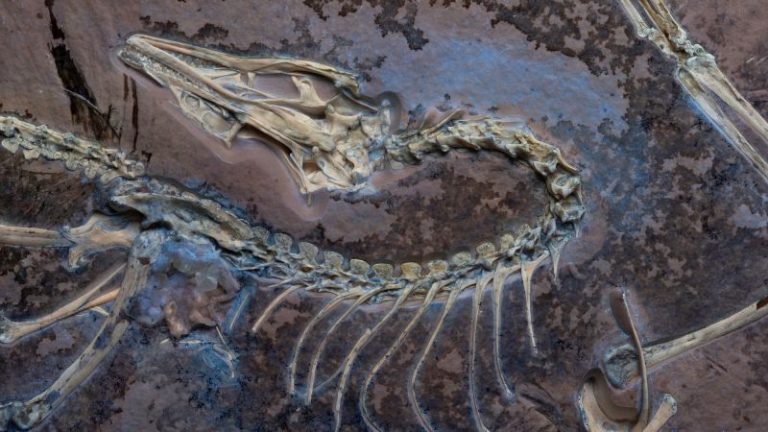

When a fossil preserves the complete body of an animal in a death installation, seeing that it observes an instantaneous in time. Several of these fossils exist for Archaeopteryx – the first known bird – and now, a remarkable specimen that has been prohibited for scientists for decades offers unique evidence on the ability of the first bird to fly.

Researchers wondered for a long time how Archaeopteryx has taken the air while most of his feather dinosaurs cousins have never left the ground, and Some supported This archaeopteryx was probably more a glider than a real leaflet. The first fossils From this jurassic winged wonder was found in southern Germany over 160 years ago and approximately 150 million years; To date, only 14 fossils have been discovered. But private collectors have taken some of these rarities, insulating fossils of the scientific study and hampering research on this pivotal moment in avian evolution.

One of these fossils has recently been acquired by the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago and has provided answers to the longtime issue of Flight in Archeopteryx. The researchers published a description of the specimen of the size of the pigeons in the journal Nature On May 14, the reports indicating that ultraviolet (UV) scanners and computed tomography (CT) had revealed fabrics and soft structures never seen in this old bird. The results included feathers indicating that the archaeopteryx could reach a fueled flight.

While most of the archaeopteryx fossil samples “are incomplete and crushed”, this fossil was just a figure and has remained unwavering by time, said the author of the main study, Dr. Jingmai O’Connor, paleontologist and associated conservative of the Fossile Reptiles of Field Museum.

“The bones are simply preserved in 3D; you really do not see that in all the other specimens,” O’Connor told CNN. “We also have more fossilized soft fabrics associated with our specimen that we have seen in any other person.”

Field Museum fossil preparers and Akiko Shinya and Constance Van Beek study co -authors worked on the specimen for more than a year. They spent hundreds of hours scanning and modeling the bone positions in three dimensions; Peeling the limestone bursts; And using UV light to shed light on the limits between the mineralized soft tissues and the rocky matrix.

Their preparation – a process that took around 1,600 hours in all, estimated O’Connor – has paid off. The researchers detected the first evidence in the archaeopteryx of a group of flight feathers called Tilts, which develop along the humerus between the elbow and the body and are an important element of any propelled flight in modern birds. Since the 1980s, scientists have hypothesized that the archaeopteryx has had turned on the duration of its humerus, said O’Connor. But this is the first time that such feathers have been found in an archaeopteryx fossil.

The surprises did not end there. The forms of scale elongated on the toes of the toes have suggested that the archaeopteryx has spent time feeding on the ground, as do modern pigeons and doves. And the bones in the roof of his mouth provided clues on the evolution of a characteristic of the skull in birds called craniens physiotherapy, the independent movement of the bones of the skull one compared to each other. This characteristic gives birds more flexibility in the way they use their spins.

“It was a” wow! “After the other,” said O’Connor.

The discovery of Tilts in particular “is an extraordinary conclusion because it suggests that the archeopteryx could indeed fly,” said Dr. Susan Chapman, an associate professor of the Department of Biological Sciences at Clemson University in South Carolina. Chapman, who was not involved in research, studies the evolution of birds using paleontology and development biology.

“The preparers of the Chicago archaeopteryx have done an exceptional job by preserving not only the bone structure, but also the impressions of the soft tissues,” Chapman told CNN in an email. “Due to their care, this almost complete specimen provides information without understanding on this transitional fossil of theropod dinosaurs to birds.”

However, Archeopteryx could probably only fly over short distances, she added. Despite the Tilts, certain adaptations for the propelled theft was missing seen in modern birds, such as specialized flight muscles and an extension of Mamail calls for a keel to anchor these muscles, Chapman said.

The museum acquired this archaeopteryx specimen in 2022 and, at the time, the president and chief executive officer of the Julian Siggers museum called that “The acquisition of the most important fossils of the Field Museum since Sue The T. Rex.”

As a link between the dinosaurs of non -avian theropods and the line that produced all modern birds, the evolutionary importance of archaeopteryx was indisputable. But in some respects, the museum made a big bet on this particular fossil, according to O’Connor. He had been in private hands since 1990 and his condition was unknown. When he arrived at the museum, scientists did not know what to expect, said O’Connor.

To say that the fossil has exceeded their expectations would be an understatement.

“When I discovered that we were going to acquire an archaeopteryx, I never thought in my wildest dreams that we were going to end up with such a spectacular specimen,” said O’Connor. “It is one of the most important macroevolutionary transitions in the history of the life of the earth, because this gives birth to the group of dinosaurs which not only survives the extinction of the final-key mass, but then becomes the most diverse group of terrebers on our planet today. So, it is a very important moment in evolution.”

The importance of these specimens underlines why scientific access should be prioritized compared to the collection of private fossils, added Chapman. When fossils are sold for lucrative purposes and a private display rather than studying, “their preparation is often poor, losing irreplaceable soft tissue structures,” she said. “In addition, the value of these specimens for understanding evolution through humanity is lost for decades.”

The Chicago Archaeopteryx probably preserves many other important details on the evolution of birds, added O’Connor. With an abundance of data already collected on the fossil and the analysis still in progress, its complete history is not yet told.

“There will be much more to come,” she said. “I hope everyone will find him as exciting as I am.”

Mindy Weisberger is a scientific writer and media producer whose work has appeared in Live Science, Scientific American and How It Works Magazine. She is the author of “Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The surprising science of the control of the parasitic spirit ”(Hopkins Press).