A major British study reveals that vegetarians, but not vegans, have a slightly high risk of hypothyroidism, raising new questions about iodine intake and the role of BMI in the interpretation of thyroid results linked to the diet.

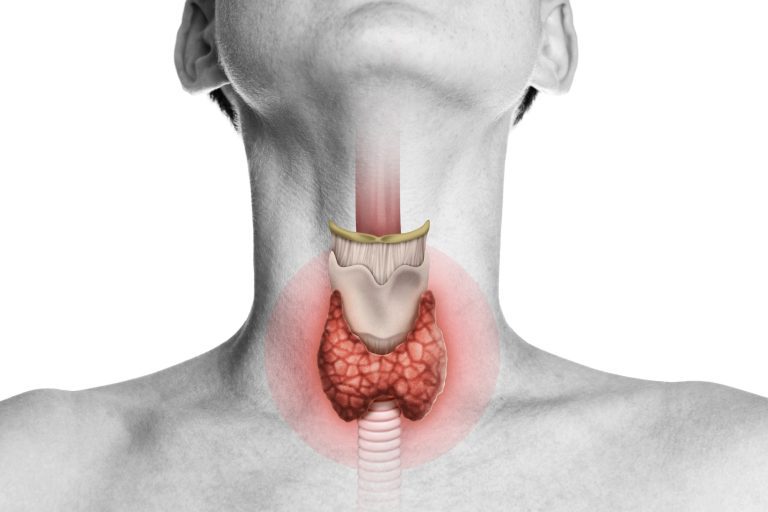

Study: Risk of hypothyroidism in meat eaters, fish eaters and vegetarians: a prospective study based on the population. Image credit: Svetazi / Shutterstock

Study: Risk of hypothyroidism in meat eaters, fish eaters and vegetarians: a prospective study based on the population. Image credit: Svetazi / Shutterstock

A study published in the journal BMC medication have found that vegetarians can have a moderately higher risk of hypothyroidism compared to high meat eaters, but only after taking into account the body mass index (BMI). No statistically significant increase in risk has been observed for vegans or pescatarians in analyzes of incident hypothyroidism; However, for current hypothyroidism at the start, a significantly significant increased risk was observed for pescatarians.

Background

The popularity of plant -based diets increases in the world due to the documents documented for health and environmental sustainability. These diets are known to reduce the risk of various chronic diseases, including cardiometabolic diseases and cancer, as well as all causes. These health benefits are particularly visible when plant-based diets are made up of high quality foods, which limits the supply of snacks, sugary drinks and ultra-transformed foods.

One of the drawbacks of plant diets is that they often lack essential nutrients such as zinc, iron, selenium, vitamin B12 or iodine. These micronutrients play a vital role in the regulation of various physiological processes, including hormonal regulation.

Iodine plays a crucial role in the biosynthesis of thyroid hormones, and iodine deficiency can lead to goiter, thyroid nodules and hypothyroidism. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a daily contribution of 150 µg to reach an adequate iodine status. For pregnant and lactating women, a daily intake of 200 µg is recommended.

Thus, the global increase in the popularity of plant -based diets causes concern about the risk of iodine deficiency and associated thyroid complications. In addition to lacking enough iodine, some cruciferous vegetables, such as cauliflower or kale, and soybean products can reduce the bioavailability of iodine due to the presence of goitrrogen compounds, further increasing the risk of hormonal complications related to iodine.

Given limited research on plant -based diets and hypothyroidism, this study aimed to assess the risk of hypothyroidism in different food groups, including high meat eaters, meat eaters, poultry eaters, fish eaters, vegetarians and vegans.

Study design

The study analyzed the data of 466,362 individuals British BiobankA prospective cohort study made up of more than 500,000 British residents aged 40 to 69. Participants were classified into six different diet groups depending on the self -declaced food intake data, including high meat eaters, weak meat eaters, poultry eaters, pescatarians (who eat fish or shellfish but no other types of meat), vegetarians and vegetarians (strict of plantar fish).

Appropriate statistical analyzes have been carried out to assess the risk of incident hypothyroidism in all diet groups.

Study results

The monitoring analysis of 466,362 individuals over a 12 -year period identified 10,831 new cases of hypothyroidism linked to potential iodine. The proportion of cases of hypothyroidism was 2% in high meat eaters, 2% in low meat eaters, 3% in poultry eaters, 2% in pescatarians, 3% in vegetarians and 3% in vegans.

The analysis of iodine intake data of a sub-sample of 207,011 participants revealed that around 92% of vegans, 44% of vegetarians and 33% of poultry eaters did not comply with the recommended daily consumption of 150 µg.

Based on socio -demographic characteristics, the study revealed that individuals with incident hypothyroidism are more likely to be women, have a higher body mass index (BMI; an obesity measure) and have a lower income.

Association between diet and the risk of hypothyroidism

Given the significant influence of BMI in the mediation of the association between food and hypothyroidism, the researchers analyzed the association with and without adjustment for this factor of influence.

The analysis revealed a significant positive association between a vegetarian diet and the risk of hypothyroidism only after the adaptation of the BMI, a statistical approach that the authors note can introduce a bias. No statistically significant association was observed for vegans, but the number of vegan participants was very low (n = 397), limiting the power to detect a difference. A positive association of the prevalence of basic hypothyroidism has been observed with a low meat diet, a poultry -based diet, a pescatarian diet and a vegetarian diet. More specifically, for hypothyroidism widespread at the start, pescatarians had a significantly significant increased risk (or = 1.10, 95% CI 1.01–1.19) after adjustment of the BMI.

Meaning study

The study reveals that vegetarians can be at a slightly higher risk of developing hypothyroidism compared to high meat eaters, but the size of the effect is modest and the association was only observed after adapting statistically to the BMI. No increased risk was found for vegans or pescatarians with regard to the hypothyroidism of incidents, but for widespread hypothyroidism, pescatarians showed a modestly increased risk after the IMC adjustment. However, this association is considerably influenced by the BMI of participants.

Given the strong influence of the BMI on the results of the study, the researchers stressed the importance of understanding whether the BMI serves as a collision or confusion in the mediation of the association between the type of diet and the risk of hypothyroidism.

While a confusion affects both exposure and the result, a collision is influenced by both. Existing evidence indicates that genetically predicted MIM can increase the risk of hypothyroidism, which suggests that BMI can confuse the association between the type of diet and hypothyroidism.

Given the consumption of lower calories in vegetarian participants, it is more likely that the diet influences BMI than that of BMI influences the effects of the diet on thyroid functions. This highlights the role of BMI as a collision.

Since BMI is influenced by the diet and by hypothyroidism by metabolic changes associated with the condition, the researchers said that adjustment for the BMI can introduce collision biases.

Since data on thyroid health before BMI measures were not available, the researchers hypothesized that unmatched hypothyroidism or the altered thyroid function affected the BMI of participants. The authors also discuss the possibility of reverse causality, where individuals with early or unmatched hypothyroidism could adopt healthier or more plant diets in response to symptoms such as weight gain.

Overall, the results of the study highlight the need for future research with data on the state of iodine and thyroid function before diagnosis. Given the role of iodine as a potential critical nutrient for vegetarians, researchers advise by considering iodine supplementation to prevent the risk of thyroid disorders.

The authors point out that, as it was an observation study, causality cannot be established and that the apparent association can be due to underlying differences in the BMI or other non-measured factors.