This year marks the centenary of the discovery of human brain waves. Few people know the story of this surprising discovery because the real story has been suppressed and lost to history. Nearly twenty years ago, I visited the laboratories of pioneering scientists in Germany and Italy in search of answers.. What I learned turned accepted history on its head and revealed a chilling story involving Nazis, brain waves, the Russian-Ukrainian war, and suicide. This story resonates with current events – Russia and Ukraine recently passed the grim milestone of 1,000 days of conflict waged under the pretext of fighting the Nazis – revealing how history, science and society are closely linked.

Human brain wavesoscillating electrical waves that constantly sweep across brain tissue, change with our thoughts and perceptions. Their value in medicine is incalculable. They reveal to doctors all kinds of neurological and psychological disorders and guide the hands of neurosurgeons in extracting diseased brain tissue that triggers seizures. Recently appreciated, their role in a healthy brain is transforming our fundamental understanding of how the brain processes information. Like waves of all types, electrical waves passing through the brain generate synchronization (think of water waves that move boats); in the case of brain waves, what is synchronized is the activity of populations of neurons.

Who discovered brain waves? What did they think they found? Why was there no Nobel Prize?

On supporting science journalism

If you enjoy this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In the most common accounts, a lone doctor, Hans Berger, recorded the first human brain waves of his patients in a psychiatric hospital in the German city of Jena in 1924 (later East Germany). He told no one what he was doing and kept his breakthrough discoveries a secret for five years. When the Nazis rose to power in the 1930s, psychiatric hospitals became the epicenter of forced sterilization and “euthanasia” aimed at promoting “racial hygiene.” Some of the methods developed at these facilities served as a prelude to industrial killing in concentration camps. As director of the Jena psychiatric hospital, Berger would have been in the thick of things. Biographies at the time of my visit indicated that Berger had committed suicide in 1941 following Nazi persecution.

“Berger was not a supporter of Hitler and therefore had to renounce service to his university; not expecting it, he was seriously injured…. (It) caused him a depression that ultimately killed him,” psychiatrist Rudolf Lemke wrote in a 1956 memorial. Lemke had worked under Berger.

To me, this seemed strange. Wouldn’t the Nazis have fired Berger just like they purged 20 percent of German academics in 1933, and mercilessly expelled or unfair “liquidated” politicians, administrators and others?

In Jena, I learned that Lemke was in fact a member of the NSDP (Nazi Party). He worked at Erbgesundheitsgericht (Hereditary Health Court) to carry out forced sterilization of mentally and physically unfit persons, broadly defined as the physically disabled, psychiatric patients, alcoholics, among others. Like many others in power, Lemke remained in Jena after the war and his anti-Semitic and anti-homosexual views were covered up by the authorities. He became director of the psychiatric clinic in Jena from 1945 to 1948.

After World War II, Jena came under the control of the Soviet Union and documents revealing a widespread cover-up were lost or destroyed. During my visit to Berger Hospital, I met neuroscientist Christoph Redies and medical historian Susanne Zimmermann, who had recently obtained Soviet archives after the fall of the Berlin Wall. They revealed that Berger was actually a Nazi sympathizer. He killed himself in hospital, not in protest but because he was suffering from depression, she said. By committing suicide, Berger’s death mirrors the suicides of many others at the time involved in Nazi atrocities.

Flipping through his dusty laboratory notebooks containing the first recordings of human brain waves, Zimmermann pointed out the fringe anti-Semitic comments he had written alongside them. She then pulled out a stack of files from the forced sterilization court proceedings where Berger served at a time when “eugenics» sought to eliminate the “unfit” from parenting. Hearing them read aloud brought back to life the horrors that had taken place there, as people begged the court not to sterilize them or their loved ones. Berger rejected all appeals, condemning them all to forced sterilization.

The hospital in Jena, Germany, where Berger discovered brain waves.

Berger’s EEG research was not well received. Believing in mental telepathy, Berger thought that brain waves might be the basis of mental telepathy, but he ultimately rejected this idea. Instead, he believed that brain waves were a type of psychic energy. Like other forms of energy, psychic energy waves could neither be created nor destroyed, but they could interact with physical phenomena. Based on this, he assumed that the work of mental cognition would cause temperature changes in the brain. He explored this idea by inserting rectal thermometers into the brains of his mental patients while they performed cognitive tasks during surgery.

Berger’s research remained little known outside of Germany until 1934, when Nobel Prize-winning neuroscientist Edgar Adrian published his experiments in the prestigious journal Brain. Adrian confirmed that so-called “Berger waves” exist, but he implicitly mocked them by showing that they changed in a water beetle when it opened and closed its eyes, in the same way that they were doing it in the Nobel laureate’s brain when he did the same. Adrian never researched brain waves further.

Berger is credited with the discovery of brain waves in humans, but animal studies predate his work. Berger also did not invent the methods he used to monitor brain activity. He applied techniques previously used in animal experiments by Adolf Beck in Lwów, Poland, in 1895, and by Angelo Mosel in Turin, Italy.

Unlike Berger, Adolf Beck’s animal studies aimed to understand how the brain works when neurons communicate through electrical impulses. At the height of his research, a Russian invasion interrupted his scientific work. In 1914, Lwów was taken by Russian invaders and renamed Lviv. Beck was captured and imprisoned in kyiv, then part of Russia (now kyiv, Ukraine).

While in prison, he wrote to the famous Russian scientist Ivan Pavlov asking for his help, and Pavlov eventually secured Beck’s release.

Beck returned to his research in Lviv and the next logical step was to search for brain waves in humans, but during World War II the Germans invaded. They established a concentration camp in Lviv where the Jewish population was exterminated. As an intellectual and a Jew, Beck was a target. When they came to take Beck to the concentration camp in 1942, he swallowed cyanide, end one’s own life rather than let the Nazis take it.

Remarkably, both pioneering brain wave scientists committed suicide because of Nazism – one as the perpetrator of Nazism, the other as the victim of Nazism.

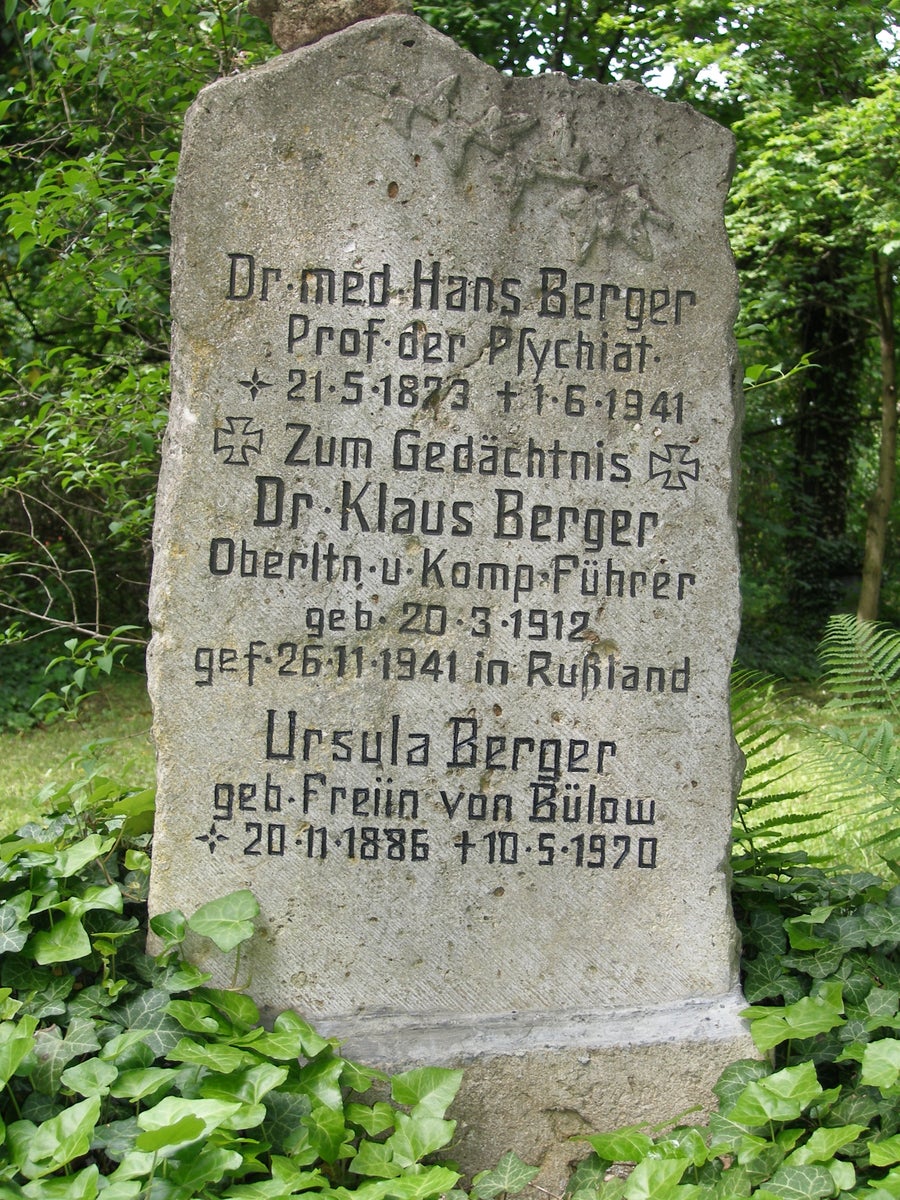

Berger’s grave in Jena.

Unbeknownst to Berger and Beck, they were not the first to record brain waves. This discovery was made by a London doctor 50 years earlier than Berger! This astonishing discovery was lost to science because the ideas were far ahead of their time, dating back to the time when the brain was an enigma and the world was lit by gas lamps and powered by steam. Imagine how much more advanced brain science and medicine would be today if this scientific discovery made in 1875 had not been lost to history for half a century.

The first person to discover brain waves was the London physician Richard Caton. Caton announced his discovery of brain waves recorded in rabbits and monkeys at the annual meeting of the British Medical Association in Edinburgh in 1875. He achieved this using a primitive device, a rope galvanometer, in which a small mirror is suspended on a wire between magnets. When an electric current (sensed by the brain in this case) passes through the device, the string twists slightly like a compass needle near a magnet. The oscillating electrical currents detected in the brain were not measured in volts, but rather in millimeters of deflection of the light beam reflected by the mirror. The published summary of his presentation “Electric Currents of the Brain” shows that with this primitive instrument the doctor correctly deduced the most important aspects of brain waves. “In every brain examined to date, the galvanometer has indicated the existence of electric currents…. The electrical currents of gray matter seem to have something to do with its function…”

Ironically, I traveled the world researching the discovery of brain waves, only to discover that the first to do so, Richard Caton, presented his findings in the United States in 1887 at Georgetown University while he was visiting family in Catonsville, Maryland. The city, which was settled by his relatives in 1787, is 30 miles from my home, adjacent to the Baltimore-Washington Airport, where I often flew from for my global research. But this fact, like his little-known research into brain waves, has been lost to history. “Read my article on the electrical currents of the brain,” he wrote in his journal. “It was well received but not understood by most of the public.”

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the opinions expressed by the author(s) are not necessarily those of Scientific American.