As Jorge Cuartas began to comb through thousands of studies, he already knew what the science of high -income countries had been suggested for a long time: spanking, slaps and trembling children do not help them to grow. But a question persisted in the background-what about the rest of the world?

For years, the so-called “cultural normativity hypothesis” has thrown a shadow on efforts to prohibit body punishment in the world. He suggested that in countries where children discipline by physical violence is a social norm, damage may not be so serious – or not exist at all.

Now Cuartas and an international team of researchers have given clarity. In a radical meta-analysis published today in Nature Human behaviorThey examined 195 studies covering 92 low and intermediate income countries (PRFR) and found no evidence that physical punishment never helps children. In fact, they found the opposite completely.

“Coherence and the strength of these results suggest that physical punishment is universally harmful to children and adolescents,” said Cuartas, assistant professor of applied psychology at New York University.

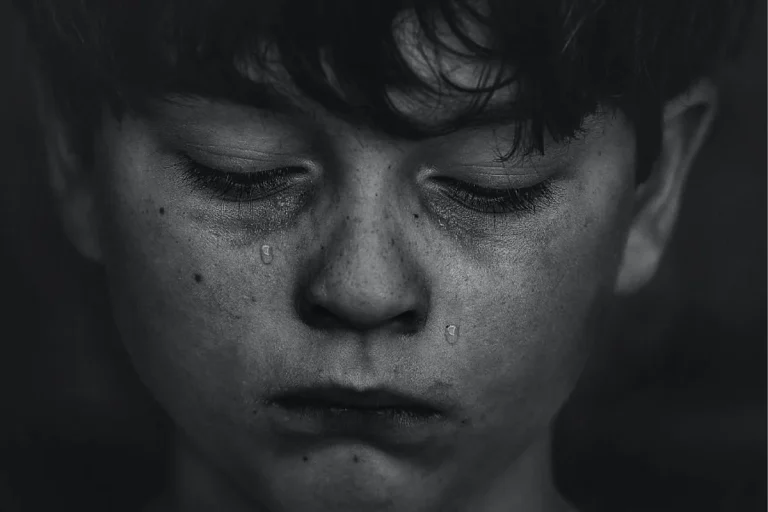

A universal damage

The research team analyzed nearly 1,500 distinct results of studies carried out between 2002 and 2024, examining how physical punishment concerns 19 different life results. These went from mental health and academic success to violent behavior and the consumption of substances.

Physical punishment was linked to negative results in 16 of the 19 categories studied. Children who were affected by caregivers were more likely to suffer from depression, anxiety and aggression. They did worse at school. They were more likely to consume drugs and become victims – or authors – of violence later in life.

Not a single positive result was observed.

A universal effect

One of the most important aspects of this study is the way he decisively refutes the idea that the misdeeds of body punishment could be limited to rich nations.

The researchers found that the harmful effects appeared in all regions of the world, from sub -Saharan Africa to South Asia via Latin America. This made no difference if a country had laws against corporal punishment or if such practices were deeply rooted in culture. In all contexts, hitting children predicted worse results.

The results are particularly urgent for LMICs, where the prevalence remains high. More than 60% of the children in these regions are physically punished by their caregivers, against only 18% in places like Canada.

“Children living in LMIs are already faced with additional contextual adversities,” notes the study, such as poverty and exposure to violence. Physical punishment, he suggests, adds another layer of risk and adversity of life.

Above all, the study explores the data. The authors explored if the severity or the moment of punishment made a difference. They found that the results have worsened when physical punishment occurred in adolescence, rather than early childhood. A severe punishment (like hitting with objects) also predicted stronger negative effects than softer forms like spanking.

But even when adjusting socio-economic differences, the design of the study and potential confusion factors, the link between physical punishment and negative results has remained strong. When parents or children said they were affected, it was systematically correlated with good mental health, weaker relationships and lower academic performance.

The study also compared physical punishment with other disciplinary approaches. Although psychological aggression (such as shouting or threatening) has also shown harmful effects, more constructive strategies – such as reasoning, elimination of privileges or positive strengthening – have not done so.

The end of violence against children

In 2006, the United Nations Secretary General called for A global ban on all forms of body punishment. Since then, 65 countries have been prohibited. Most are high income nations. This study can add momentum to the growing thrust of legal reforms in PRFM.

“Additional research is necessary to identify effective strategies to prevent physical sanctions worldwide and ensure that children are protected from all forms of violence,” said Cuartas.

Although the study does not make causal claims – ethically, researchers cannot have randomly affect children to strike or not – it relies on decades of evidence and uses sophisticated statistical techniques to take into account confusion factors.

Even when the analysis focused only on studies with the strongest controls, the conclusions were held.

For many decision -makers and educators, especially in contexts where corporal punishment remains the norm, this study is probably alarm.

In the development sciences, few results are so consistent with all cultures, methodologies and generations. However, here, the message is undoubtedly.

Hitting children – whether in a Lagos classroom, a village in Bangladesh or a house in the rural Guatemala – does not make them stronger, smarter or more obedient. It hurts them.

And for researchers like Cuartas, it is time to pass beyond knowing whether the body punishments are harmful.

The answer is yes. The question is now how to stop it.