Invite brief

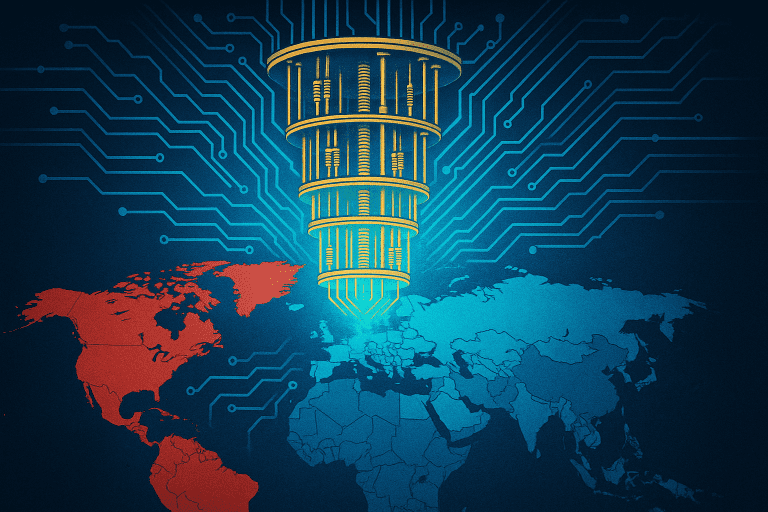

- A new study warns that restrictive quantum technology policies strengthen global inequalities by excluding the world South from access to emerging quantum innovations.

- Export controls of the United States, EU and China limit access to quantum and communication equipment, undermining research capacity and infrastructure development in poor countries.

- The authors suggest that the absence of a cooperative world framework could leave the world South more vulnerable to security threats and deepen digital dependence.

The countries of the southern worldwide may be excluded from the quantum revolution – as well as its economic, technological and security advantages – due to growing export controls, compartmentalized research initiatives and national security problems, supports a new analysis of policies.

In the first A series of articles on quantum technologies Published by the Policy Journal SecurelyYResearchers Michael Karanicolas, from the University of Dalhousie, and Alessia Zornetta, of UCLA law, examine how the geopolitics of emerging quantum technologies reproduce long -standing models of technological exclusion. The authors argue that the absence of significant interventions, Quantum could become another engine of global inequality, which threatens to lock the poorest nations of the next era of technological and economic development.

Export controls and flare holder

The authors retrace the roots of this fracture with export control diets which develop quickly in response to the strategic potential of quantum systems. Since 2020, governments in the United States, the EU and China have implemented targeted restrictions on hardware, software and communication systems with quantum habilitation.

The United States began to tighten its grip in 2021 by prohibiting exports to eight Chinese quantum companies, before deploying wider license requirements at the end of 2024 which affects complete quantum systems. The restrictions of the European Union, implemented through a double -use framework, limit the exports of systems which exceed 34 qubits – capping effective access to devices which could perform significant quantum calculations. China has also tightened, adding quantum encryption and ultra-basic temperature components to its protected export list.

Karanicolas and Zornetta argue that if these restrictions are generally justified for reasons of national security – in particular as a means of slowing down the progress of China – they inadvertently harm the world, which does not have the capital and the research capacity to build these technologies at the national level. Consequently, many nations are excluded not only from the development of their own systems, but also from the deployment of quantum technologies which should underline security, communications and new generation health infrastructure.

“These technological controls create concentric access circles; Allies benefit from a privileged exchange while competitors are faced with growing challenges in the creation of national quantum research programs, “write researchers. “Although these controls are often justified as a means of forcing rivals – in particular China – they also have the involuntary effect of locking researchers and institutions in the world.”

The authors added that the privileged allies benefiting from exchange privileges and others are faced with obstacles to the entrance. This structure reflects the technological blocks of the era of the Cold War and undermines any notion of a quantum future shared on a global scale.

Sculpture collaboration – and their limits

Even when the technological controls are tightening, the report notes that a certain flexibility has emerged in the collaboration of research. Faced with talent shortages and international interdependence, the main quantum countries have exceptions to share knowledge.

About half of the quantum professionals working in the United States are foreign nationals. Many automated quantum research documents in the United States include international co-authors. The government responded by authorizing collaboration with these people – the institutions provided to keep detailed files.

The EU also moved its position, softening the initial restrictions which limited the financing of research to the Member States. Cooperation agreements are now in place with the United Kingdom, and other talks are underway with Switzerland.

On the other hand, China traces a more island path, focused on the development of a self-sufficient quantum workforce and the reduction of foreign partnerships. This divergence in strategies – collaborative opening in the United States and the EU, inner consolidation in China – highlights a critical political tension: to balance strategic control with global scientific progress.

But according to Karanicolas and Zornetta, these knowledge sharing frameworks still fail. Researchers on the world South often lack access to the same networks, funding and institutional supports, disadvantage even in otherwise “open” collaborations.

Areas, such as world South, could be unexploited sources of desperately necessary quantum talents, suggests the article.

Security, sovereignty and economic issues

The implications go far beyond the academic world and the authors emphasize that some of the large number of use cases quantum technology could ignite. As quantum technology matures, it could upset the whole sectors. Quantum IT could break encryption systems that currently protect financial institutions, defense networks and communication tools. Quantum detection could revolutionize imagery and environmental surveillance. Quantum communications could constitute the basis of an ultra-secure infrastructure.

Advanced savings, including those of the EU and North America, are already investing in these capacities. Canada and the EU explore national quantum communication networks, and industry players are preparing to deploy quantum cybersecurity tools.

For world southern countries, the risks are double: they can miss both defensive capacities to guarantee their infrastructure and economic leverage to develop competitive industries in improved quantum fields.

“Without significant access to quantum resources, the world South can be confronted with a triple disadvantage,” write Karanicolas and Zornetta, describing the drawbacks. “First, their security infrastructure could become more and more vulnerable because quantum IT threatens to break the existing encryption protocols. Second, their economic competitiveness could decrease because they lack the opportunities to develop improved quantum technologies. triple disadvantage.

The net effect could be a deeper and more sustainable form of digital dependence – which amplifies existing inequalities and limits the capacity of the world South to trace its own development path.

A call for a new executive

The authors indicate a historic precedent to manage sensitive technologies. In 1953, the president “Atoms for Peace” of President Eisenhower tried to share nuclear energy technology while limiting its use in the development of weapons. This vision finally shaped the global nuclear non-proliferation regime.

Karanicolas and Zornetta ask if a similar framework – they delete it “qubits for peace” – could be viable for quantum technology. The objective would be to allow peaceful applications of quantum computing, detection and communication in less developed countries, while protecting military and intelligence uses.

They don’t expect it to be easy. In the fragmented geopolitical environment today, it is unlikely that the United States or its allies can command the authority necessary to direct such an initiative. It is not clear that the countries of the world of world would accept new restrictions, especially when they are already faced with drawbacks. The difficulty of separating civil and military quantum applications – especially in encryption – complicates things more.

In practice, the authors suggest that the world is more likely to derive towards a fragmented quantum landscape where some countries hold the keys to secure infrastructure, and others are forced to catch up with limited tools.

The quantum moment

The central study of the study is that the world repeats a dangerous scheme. As with the Internet and the biotechnology that seized it, the advantages of transformative technology are accumulated by the countries that develop it first.

But Quantum differs with one respect. Its security implications are immediate. If quantum computers are able to break today’s encryption protocols in the near future – a risk that many governments are preparing – then the digital infrastructure of quantum resilience could be exposed in a decade.

In this scenario, the quantum fracture would not only slow down development in the world of world, it would actively place these nations at risk.

The authors call for a more inclusive collaboration, expanded research frameworks and a reassessment of export policies. It remains to be seen whether governments are willing to act on these proposals. But the issues are clear.

“The modification of the approach of research collaboration by major quantum powers could point out a potential path to follow, with strategic sharing frameworks of enlarged knowledge to include the global interests of the South and reject the quantum fracture,” write Karanicolas and Zornetta. “While governments pay resources in the progression of these technologies, they must consider the strategies to ensure that their advantages do not remain partitioned in a handful of rich countries and are accessible to everyone.”

Karanicolas is an associate professor of law and president of James S. Palmer in public policy and law of Dalhousie University. Zornetta is a doctoral candidate at UCLA Law, specializing in the regulation of content moderation practices by online platforms.

Just safety is a diary of digital law and independent, non -supporter and independent policy which raises discourse on national security, democracy and the rule of law and rights. This is part of the organizations Governing the quantum revolution series.