But not all the kangaroos were. In new research Published today in Plos One, we found giant kangaroos that once lived in eastern Australia were much less mobile, which makes them vulnerable to changes under local environmental conditions.

We have discovered fossilized teeth of the genus giant now turned off Protemnodon In Mount Etna Caves, north of Rockhampton, in the center-east of Queensland. The analysis of the teeth gave us an overview of the past movements of these extinct giants, there are hundreds of thousands of years.

Our results show Protemnodon has not fueled over large distances, living rather in a luxuriant and stable Utopia of tropical forests. However, this utopia began to decline when The climate has become drier with more pronounced seasons – Doom spelled for the giant roos of Mont Etna.

Caves de l’Etna du Mount

THE Etna Mount Caves National Park and nearby Capricorn caves hold remarkable records of life over hundreds of thousands of years.

Fossils have accumulated in caves because they acted like giant traps and also laies of predators such as thylacines, Tasmanian devils, marsupial lions, owls, owls, owls, owls, owls, owls, owls, owls, owls, owls, owls, owls Ghost bats.

Large parts of the region were once extracted from lime and cement. One of us (Hocknull) has worked in close collaboration with mines managers to eliminate and store fossil deposits in complete safety of caves for destroyed for Scientific research that always continues.

As part of our study, we released with fossils using an approach called dating from the series of uranium, and the sediments around them with a different technique called luminescence dating.

Our results suggest that giant kangaroos lived around the caves of at least 500,000 years ago at around 280,000 years. After that, they disappeared from the fossil file of Mont Etna.

At the time, Mont Etna welcomed a rich habitat of tropical forest, comparable to modern New Guinea. While the climate has become drier between 280,000 and 205,000 years old, species living with the tropical forest Protemnodon Disappeared from the area, replaced by those adapted to a dry and arid environment.

You are what you eat

Our study examined how far Protemnodon traveled to find food. The general tendency of mammals is that the biggest creatures go further. This trend is valid for modern kangaroos, we therefore expected that giant kangaroos that Protemnodon would also have had large ranges.

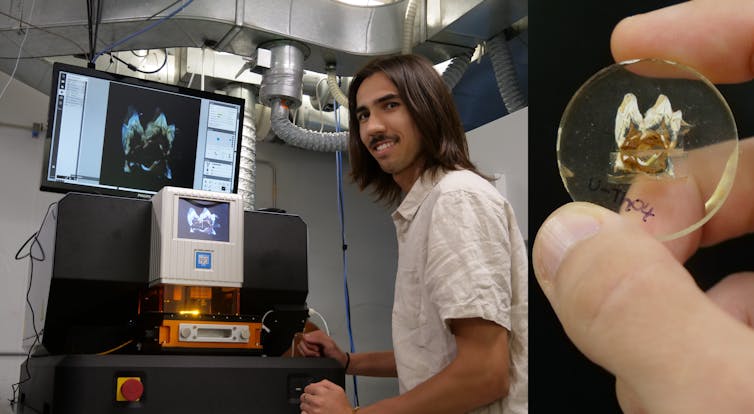

Teeth Save a chemical signature food you eat. Looking at different isotopes of the strontium element in the enamel of the teeth, we can study the ranges of food search from extinct animals.

The variable abundances of strontium isotopes reflect the chemical footprint of plants that an animal has eaten, as well as geology and soils where the plant has developed. By matching chemical signatures in the teeth to local signatures in the environment, we could estimate where these old animals went to obtain food.

Eat local, die local

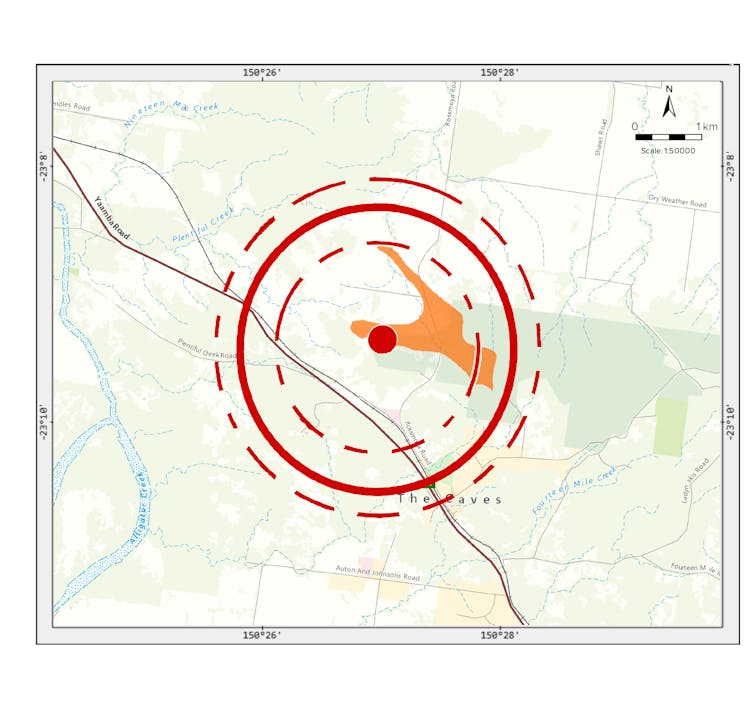

Our results have shown Protemnodon From Mount Etna did not travel far beyond the local limestone in which the caves and fossils were found. It is a much smaller range that we have planned the range according to their body mass.

We believe that the small range of food from Protemnodon In Mont Etna, there was an adaptation to millions of stable food supply in the tropical forest. They probably didn’t need to travel to find food.

Fossil evidence also suggests certain species of Protemnodon Four -legged market Rather than jump. This would have forced their ability to browse great distances, but it is an excellent strategy for Live in tropical forests.

It remains to answer a question: if they did not need to move far to find food, why did they become so big in the first place?

A local adaptation or a trait of species?

The extinction of the megafauna of Australia – long lively animals such as the “lion marsupial” Thylacoleo And the three tonnes Diprotodon – has long been debated. It has often been assumed that megafauna species responded in the same way to environmental changes wherever they lived.

However, we may have underestimated the role of local adaptations. This is particularly true for Protemnodonwith A recent study suggesting a significant variation in food and movement in different environments.

Small ranges of similar food has been suggested For Protemnodon who lived near the caves of Bingara and Wellington, in New South Wales. Maybe it was common to Protemnodon The populations in stable habitats in eastern Australia are homeodia – and this may have proven the heel of their Achilles when the environmental conditions have changed.

Extinction, one by a

As a rule, creatures with a small vital area have a limited capacity to move elsewhere. So if something happens to their local home, they can be roughly trouble.

At Mount Etna, Protemnodon Prospered for hundreds of thousands of years in the stable environment of the tropical forest. But as the environment has become more arid and increasingly unequal resources, they may not have been able to cross the growing gaps between forest plots or withdraw elsewhere.

A key result of our study is that Protodemnon was locally extinguished at MT Etna long before humans appeared, which excludes human influence.

The techniques used in this study will help us know how the megafauna of Australia responded in more detail to changing environments. This approach moves away the debate on the extinction of the Australian megafauna far from the traditional hypotheses of continental capture – we can rather examine local populations in specific sites, and understand the unique factors stimulating local extinction events.![]()

Christopher Laurikainen GaeteDoctoral student candidate, University of Wollongong; Anthony DossetoProfessor of geochemistry, University of Wollongong; Lee ArnoldAssociate professor in Earth Sciences, University of Adelaide, University of WollongongAnd Scott HocknullScientist and principal curator, geosciences, Queensland museum and honorary researcher, Melbourne University

This article is republished from The conversation Under a creative communs license. Read it original article.

(Authors: Christopher Laurikainen Gaete Doctoral student, University of Wollongong DOSSET ANTHONY Professor of Geochemistry, University of WollonGong Lee Arnold Associate Professor in Earth Sciences, University of Adélaïde, University of Wollongong Scott Hocknull Scientist and principal curator, geosciences, Queensland museum and honorary researcher, University of Melbourne)

(Declaration of disclosure: The authors do not work, consult, do not have or receive funding from a company or an organization which would benefit from this article and would not have revealed any relevant affiliation beyond their academic appointment.)