CERN researchers in 2012, including its director general of the time, Rolf-Dieter Heuer (second on the right) and the current director general Fabiola Gianotti (center), are impatiently awaiting confirmation that the Higgs Boson had finally been found.Credit: Denis Balibouse / Reuters

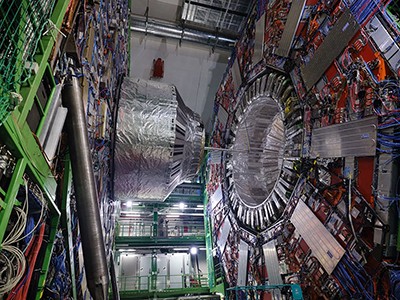

Frais of their history Discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012The researchers using the great collision of Hadrons du CERN (LHC), the main particle accelerator of the European Particle-Physical Laboratory near Geneva, Switzerland, threw their objective on an even greater task. They aimed to explore what is beyond the standard model of particle physics, the spectacularly successful – and frustrating description – – fundamental particles and the forces that act. And yet, More than a decade laterThe LHC has found no clue of new physics. The nature of the dark matter which highly prevails over the quantity of normal matter in the universe and the Higgs boson itself remain elusive. And the clock turns. In the early 2040s, the LHC, which had a 27 -kilometer circumference, will reach the limits of its usefulness. The question is, what should follow?

The largest machine in science: inside the fight to build the next collision of giant particles

The response from the CERN management is an even more massive accelerator, this time with a 90 -kilometer circumference: FCircular collision Uture (FCC), which will ultimately break the particles together eight times the energy that the LHC makes. If it is approved by the Laboratory Director, the CERN Council, this extremely consecutive decision will establish the course of high energy physics for the rest of the century, with important implications for science, international collaboration and society. But the FCC plan is controversial and faces big challenges to be funded (see Nature 639560–563; 2025).

A large part of the technology necessary to get there does not yet exist – including superconductive magnets strong enough to fold the high -energy particle beams around the accelerator tunnel. For this reason, a first phase of the project would involve digging the tunnel and using existing technology to install a lower energy machine designed to study known particles, including the thinner Higgs boson. Particle collisions with the highest energies would come later, from around 2070.

Many physicists say that particle physics needs a long-term ambition like this. But not everyone is convinced of how to proceed. The FCC does not have the clear justification that the LHC had to find the Higgs boson – the last remaining particle predicted by the standard model. Many physicists agree that there is a case to explore the existence of new particles to higher energies, but what they do not agree on, it is at what cost.

The SuperCollider of $ 17 billion from the CERN in question because the higher funder criticizes the cost

Alternative plans exist, including the designs of linear collisides and the options to reuse the existing LHC tunnel. A group of physicists appointed by the CERN Council currently leads to a “update of the strategy”, requesting the contribution of the physics community. Researchers from around the world submit proposals to shed light on this process and they will discuss ideas during a municipal style meeting in Venice, Italy, in June. The strategy group will then submit its recommendations to the Council in December.

The debate is already vigorous. Some particles physicists are concerned that if the FCC gets the green light, it will take so long to build that even their students will not be able to harvest the advantages during their professional life. But the projects which are transmitted by the generations are precisely what makes the FCC in value, say others. Others are always concerned about a perception of physicists who work on other types of experience that CERN scientists have a “feeling of law” – that they deserve more money than other areas simply because they have investigated the highest energies.

The costs of exceeding are yet another concern. If the CERN surpassing itself to finance its next major project, it could end up not continuing other activities. Although the LHC gets the most big titles – and the next big collision will also – CERN is much more than its flagship product. The laboratory has organized advanced experiences on antimatter and cloud physics and has built a cutting -edge cosmic shelter detector that has been flying on the international space station since 2011. Its installations have been a test field to validate technologies for two of the largest projects in the world currently under construction, Japan hyper-kamiokande experience And Deep underground neutrino experience (Dune) in the United States, which will both study neutrinos. These new technologies are also important for CERN, which is why endangering them is not an intelligent thing to do.

It is not clear if, or which, countries could intensify to fill the financing gaps. Germany – which already provides 20% of the laboratory budget – in particular, has already pointed out that he will not increase his contributions.

The new CERN chief undertakes to move forward with a supercollider of $ 17 billion

Since its creation over 70 years ago, when Europe has emerged from the shadow of the Second World War, CERN has been a paragon of multilateral collaboration. European countries have found in the CERN a source of common pride and a tool to extend the prestige and scientific ties of the continent around the world. It now has 24 countries as full members, as well as many others, including the United States, which contribute to its activities and the community in a crucial manner. Several other international organizations, including the European Molecular Biology Laboratory and the Southern European Observatory, were modeled after the CERN. Other scientific communities which do not have such an authoritarian point of reference – such as those that study cosmic rays or gravitational waves – have sucked in to imitate the governance model of the laboratory or to receive its support.

The CERN council will now face a difficult decision. Unless some nations present themselves to a major silver infusion, the FCC faces an uncertain perspective of being funded. But to wait too long could mean that there will be a big gap between the opening of the new installation and the closure of the LHC, and a precious expertise could end up being lost.

Although physicists can disagree on what CERN should do, they care almost unanimously about the future of the laboratory. They and their leaders must now argue why European taxpayers, who finance most of the annual budget of the laboratory should also care. The issues go beyond science, and even beyond Europe.