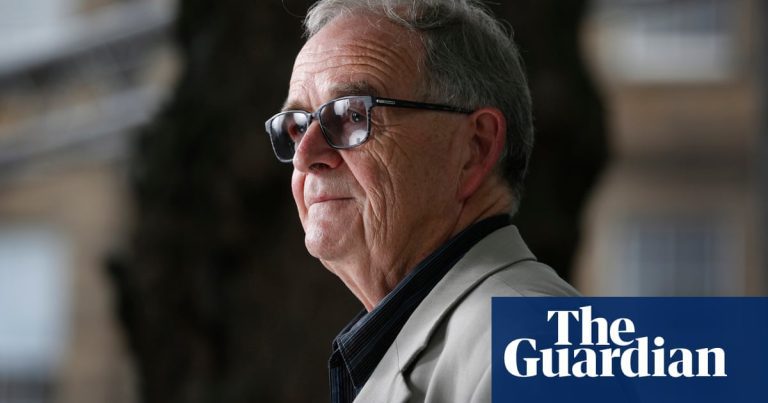

Tim Radford, the former scientific editor and Guardian mentor to a generation of writers who followed his traces, died at the age of 84.

His reports covered a width of subjects of genetically modified crops and the environmental impact of greenhouse gases when the animals arrived and the Discovery of gravitational wavesThe undulations of the fabric of predicted space-time for the first time by Albert Einstein a century earlier.

The tributes to Radford recall a polymathe whose contagious enthusiasm for science and talent for having transformed a sentence praised university professors as much as wider readership.

It was a role in which he reveling, saying that it was one of the rare jobs in journalism where a writer was able to tell stories that no one had previously told.

“Tim was a polymathe,” said Sir Martin Rees, the royal astronomer. “He wrote for non-specialists, believing that science was part of our culture and that key ideas could be made accessible to everyone.

“Even when his subject was the one I thought I understood, he offered new ideas and new metaphors. People with its eloquence and intellectual range are too rare – we will unfortunately and largely miss it. »»

Sir Paul Nurse, the Nobel Prize winner who will become president of the Royal Society for the second time later this year, entitled Radford “an excellent writer”, adding: “We will all miss.”

Radford was born in New Zealand in 1940 and studied at the Sacred Heart College in Auckland. He joined the New Zealand Herald as a journalist at the age of 16 and moved to the United Kingdom in 1961. After a brief fate as an information officer of Whitehall, he spent the rest of his Career in newspapers, joining The Guardian as a sub-editor in 1973. He worked as editor -in -chief, editor -in -chief and literary publisher before becoming a scientific publisher in 1992.

Claire Armittead, former literary editor at The Guardian, said: “Tim was the best type of journalist: infinitely curious and excited by the immensity and variety of the universe, and indulgent of those who did not have its ability to understand it. “

Radford won the Association of British Science Writers awards on four times and received a life prize in 2004, the first year it ran. The following year, the prize was awarded to Sir David attent Boil.

Beyond his journalism, Radford was a revered mentor for many promising writers. By being invited to do training on the media, he denounced 25 commandments For budding journalists. The rules remain required to read today. We urge writers to imagine a small sign on their desk which declares: “No one has to read this shit.”

He also offered more tailor -made advice. When a journalist admitted to feel paralyzed by the responsibility of the work, he replied: “My experience of journalism is that if you are not hunted down by fear, panic and a deep feeling of insufficiency, then you cheat. The complacency does not get good stories, never. “”

He highlighted the importance of simple words, clear ideas and short sentences, without forgetting a feeling of irreverence. In a demonstration of the latter, he reported on the long -awaited response of the government of Blair at the risk of slamming asteroids in the earth: A new information center to build in Leicester.

“He could speak as easily to the Nobel Prize winners as undergraduate students, and he could make any subject, as obscure, fascinating, could be published,” said Chris Mihill, a former Guardian medical correspondent. “He was a wonderful storyteller and could completely capture an audience, but he always ended on an self-depreciating note. Then, leaving, he would tell you casually why Shakespeare prefigured Wittgenstein about 400 years old. »»

Radford wrote three books: the life crisis on earth, the address book and the consolations of physics. Will Francis, his agent of Janklow & Nesbit, said: “From the age of 16, jumping from the gateway to the bridge of a cruise ship that entered the port of Auckland to interview Robert Mitchum, to the journalist Patrician scientist, a paternal figure to an entire generation of writers, Tim has never lost his extraordinary combination of insight and intellectual humility. As he said: “You start all journalism with understanding that it is very easy to be mistaken.” »»

Alok Jha, editor -in -chief of science and technology for The Economist, “said:” Tim was the best of us, and such a huge pleasure. He didn’t know everything – from cosmic inflation to Neanderthal culture – but he has effortlessly launched these strands of knowledge in magic and captivating stories. He was inexhaustible in his kindness, his mentoring and his support for many generations of writers and scientists who wanted to help the world understand complex ideas. »»

Radford is survived by two children, a granddaughter and a great-granddaughter.